Analysis: what the number and spread of players and clubs tells us about the geography of hurling

In recent years, the population argument has been a theme of the debate, and in some cases critique, of Dublin's dominance of the All Ireland senior football championship between 2015 and 2020. This has even extended to dedicated websites complete with 'split the dubs’ merchandise.

But population considerations have rarely if ever been applied to hurling, at least in relation to all 32 counties at the same time. In a 1993 article titled 'The geography of hurling', Kevin Whelan considered a fundamental question: ‘why is hurling currently popular in a compact region centered on east Munster and south Leinster, and in isolated pockets of the Glens of Antrim and in the Ards Peninsula of County Down?’

Undoubtedly, there are a complex mix of historical political, social, and cultural factors that may explain why a certain sport is popular in a certain place at a certain time. Whle those areas remain hotbeds of the game’s popularity (although not exclusively), the answer to that question is no more obvious now than in 1993.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ GAA podcast in June 2020, Derry's Chrissy McKaigue and Neil McManus of Antrim join RTÉ Sport's Mikey Stafford and Rory O'Neill to discuss the idea of creating a combined Ulster hurling team to compete in the Liam MacCarthy

An interesting geographical assertion did make an appearance on The Sunday Game in 2010. Analysing his side's victory over Dublin at Croke Park, Antrim manager Dinny Cahill stated that 'geographically, Antrim is a long way away from hurling counties'. It is safe to assume that his own county, Tipperary, was among those hurling counties. Twelve years on, Antrim is still as far away from east Munster, and the Ards Peninsula still as removed from south Leinster as it always will be, so geography alone does not sustain the popularity of hurling.

However, it is possible to use the most recently published GAA annual report to create a census of hurling from the breakdown of team registrations for the year from June 2021 to May 2022. For the purposes of this exercise, we are assuming that all 8,136 registered hurling teams (categorised as Adult, U20 or Youth teams in the report) had an average of 20 players (a starting 15 and five substitutes for argument's sake). The comparative strength of hurling populations that emerge are valid so long as this measure is applied for all teams at all levels across the country consistently.

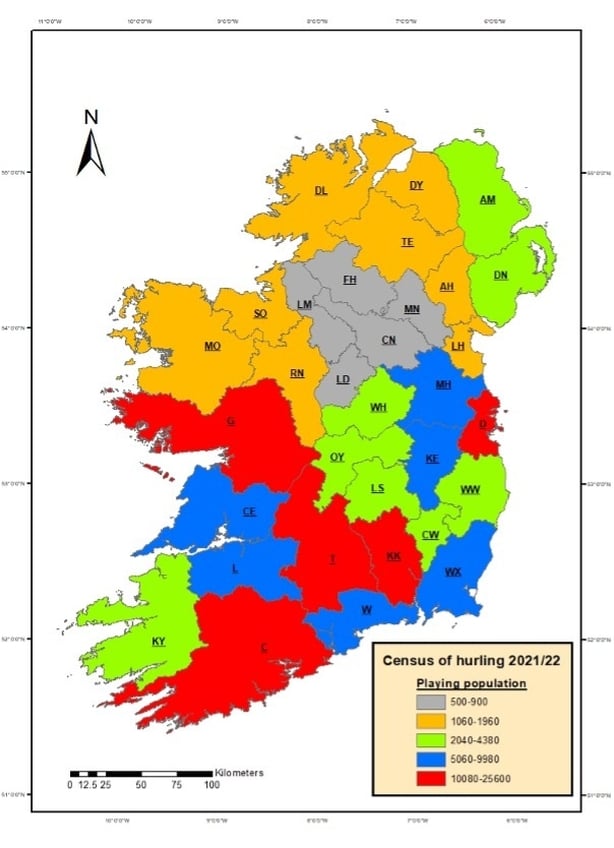

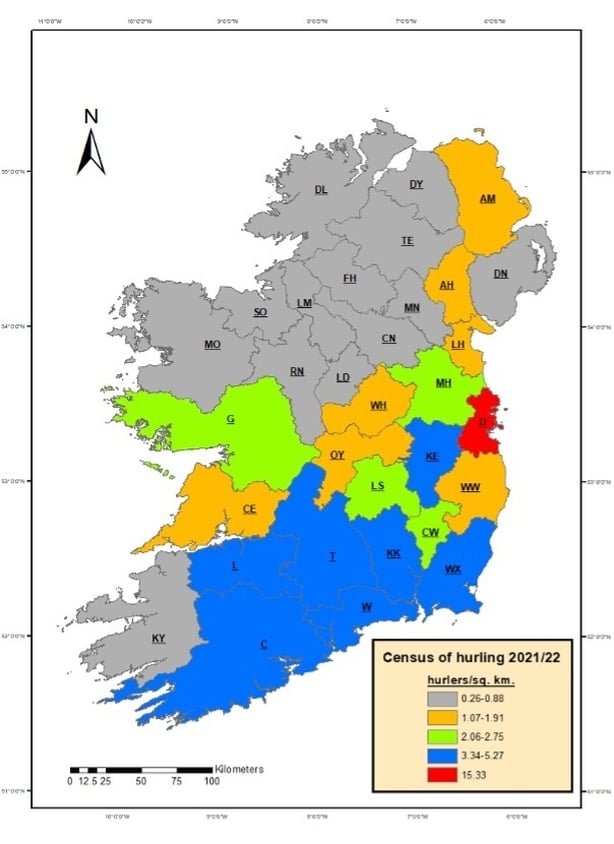

For ease of identification in the maps that follow, northern counties have been assigned similar codes as those on car registration plates in the south (Antrim=AM; Armagh=AH; Down=DN; Derry=DY; Fermanagh=FH; and Tyrone=TE].

If Whelan's 1993 analysis had identified some of the areas in which the game was popular, Map 1 suggests not much has changed in almost 30 years broadly speaking. What we can now add to that analysis is identifying the area in which the game of hurling is least popular, that area where a pocket of counties in south Ulster, northeast Connacht and northwest Leinster intersect.

Moreover, there is a clear north-south divide in the game’s popularity that is not solely connected to the political border. The 15 northernmost counties on the island have an average hurling population of approx. 1,387 players. By contrast, the 17 counties to the south of that bloc have a hurling population of approx. 8,348 players on average.

The game’s uneven concentration is further reflected in that Cork’s 210 adult hurling teams is considerably more than the 131 for the entire province of Ulster. Tipperary’s 50 teams at under 20 level alone is more than all the youth hurling teams of Fermanagh (28), Leitrim (21), Longford (27), Monaghan (36), Roscommon (49), Sligo (48), and Tyrone (45).

Dublin’s disproportionate receipt of games development investment and team expenses in recent years, in addition to that county’s massive population may have tainted, for many, their recent dominance of the football championship. But when it comes to hurling population alone, Limerick’s recent dominance of the hurling championship appears to have no apparent advantage over its rivals. Indeed, Limerick (9,980) has the sixth largest hurling playing population in Ireland currently, behind Cork (25,600), Tipperary (14,260), Dublin (13,980), Galway (12,520), and Kilkenny (10,080).

If we are to consider Map 2 a measurement of hurling density, such an indicator might better reflect the health of the game rather than its overall popularity. Unsurprisingly, only Dublin (15.33/km2) contains at least one starting team worth of hurlers per square kilometre. The next most densely populated counties in terms of hurlers are Waterford (5.27/km2), and Kilkenny (4.89 km2). More pressing a concern, arguably, is that 13 counties of Ireland have less than one hurler per square kilometre, from Down (0.83/km2) in the northeast to Kerry(0.58/km2) in the southwest and back to Donegal (0.40/km2) in the northwest.

Perhaps in years to come, the growing number of "social hurling" groupings might also be included in in this kind of consideration of the game's popularity, such as those in Cork, Dublin and Belfast's "halfpacehurling", for example.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ