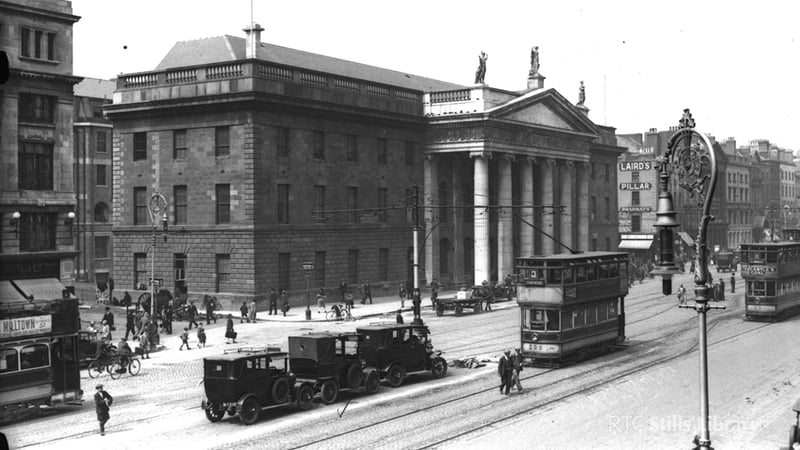

The Custom House was the last symbol of British civil administration in Ireland. The aim of the Republicans was to make the country ungovernable and in this they were quite successful. As early as 1918, in response to the threat of conscription, Dick McKee, O/C of the Dublin Brigade, suggested they attack the building.

Dick McKee. Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum/OPW KMGLM 19PC-3N12-14

McKee again put forward his plan to IRA GHQ in early 1920 but GHQ had a much bigger operation in mind – to destroy the local tax offices around the country. The IRA successfully carried out these attacks in March/April 1920, thus leaving the only copies of the Income Tax records in one place; the Custom House. It was not a matter of if the Custom House was to be attacked, but when.

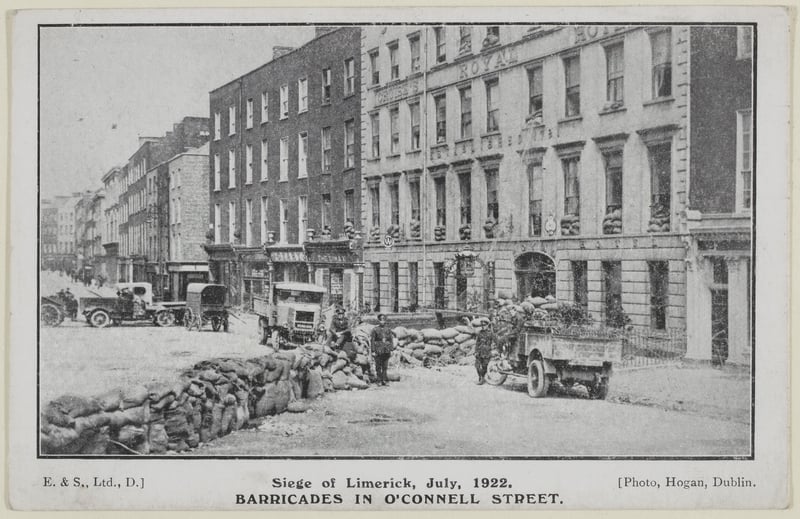

The Custom House

De Valera takes charge

Éamon de Valera's returned from his fundraising tour in America in December 1920. He had seen how the international media was portraying events in Ireland. Oscar Traynor, O/C of the Dublin Brigade IRA, recalled in his BMH Witness Statement:

… He [De Valera] made it clear that something in the nature of a big action in Dublin was necessary in order to bring public opinion abroad to bear on the question of Ireland's case.

De Valera suggested two possible targets, Beggars Bush barracks or the Custom House, 'the administrative heart of the British Civil Service machine in this country.'

Traynor suggested that they should attack the Custom House. The Custom House held all local government records, including all the tax files for Ireland. Commandant Michael Kelly who wrote about the operation in 1942 stated, if the operation was a success,

'its destruction would reduce the most important branch of British Civil Government in Ireland to virtual impotence and would, in addition, inflict on her a financial loss of about two million pounds.'

Planning the operation

Three months was spent planning the operation. It would involve sections of all of the battalions of the Dublin Brigade, IRA. It was very easy to carry out surveillance. By simply carrying official looking envelopes, Oscar Traynor was able to walk freely through the building. Plans came from a friendly contact in the Board of Works. Intelligence came from a number of IRA men who worked in the building.

Oscar Traynor

Harry Colley was one such person; he observed that for the operation to be any way successful, they needed to destroy the Will Room, which was on the ground floor in the middle of the building, under the dome. Recalling in his Witness Statement Colley stated '…that this was the only combustible part of the building capable of forming a large fire.'

Tom Ennis, O/C 2nd Battalion was in charge of the operation. His men would carry out the assault inside, with men from the other Battalions outside providing cover. It was estimated that at least 120 men would be needed for the attack, but as new research has shown, close to 300 men and a number of women were involved.

Collins was not happy with the amount of men required as he feared they could be lost. Writing in 1942, Commandant Michael Kelly stated that de Valera's response to this was,

'…that if these 120 men were lost and the job accomplished, the sacrifice would be well justified.'

The Fire Brigade, whose members included both IRA and ICA, were vital in providing information on the best way to burn such a large building. The operation was to last twenty-five minutes. Each man would have six rounds of ammunition.

The action begins

On the morning of the 25th May, the Volunteers were ordered to meet at specified locations in and around the Custom House. At 12.55pm, Ennis and his men, with some members of the Squad entered the building, each carrying tins of paraffin.

All the other battalions including the Active Service Unit (ASU) took up positions in the surrounding area and occupied the Fire Stations around the city. As the Volunteers entered the building, the 5th Battalion cut the communications from the Custom House.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

RTE News marks the centenary of the burning of the Custom House

The Volunteers gathered the staff and brought them to the Central Hall to be supervised by the ASU and Squad. Once the rooms were cleared they prepared to set them alight. When all the rooms were ready, Tom Ennis, with one whistle blast would signal that the rooms were to be fired. Once done, two whistle blasts would indicate the completion of the job and evacuation.

Daniel McAleese, an employee in the Custom House, recalled in his Witness Statement:

'… Several young men passed us carrying tins of petrol. One of the leaders announced that the Custom House was being set on fire and warned us against causing any commotion.'

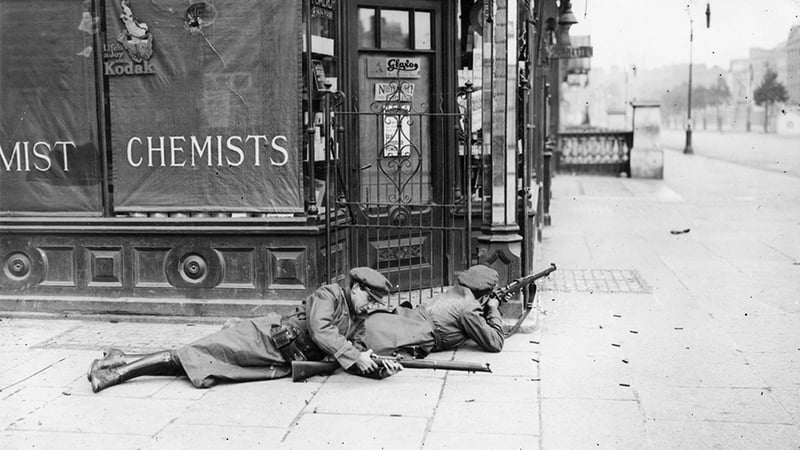

However, word did get to the military that the Custom House was being attacked and a party of troops was dispatched. The Volunteers had been told that they were not to open fire first. Some Volunteers, surprised at seeing the military, opened fire as the troops came by Liberty Hall.

Preparations for firing the building were not complete. When they heard the shots; the men inside returned fire. In the confusion the blast of a whistle was heard, yet not all of the rooms were ready. The men were ordered to finish their task, causing a delay of a few minutes, but the building was set alight.

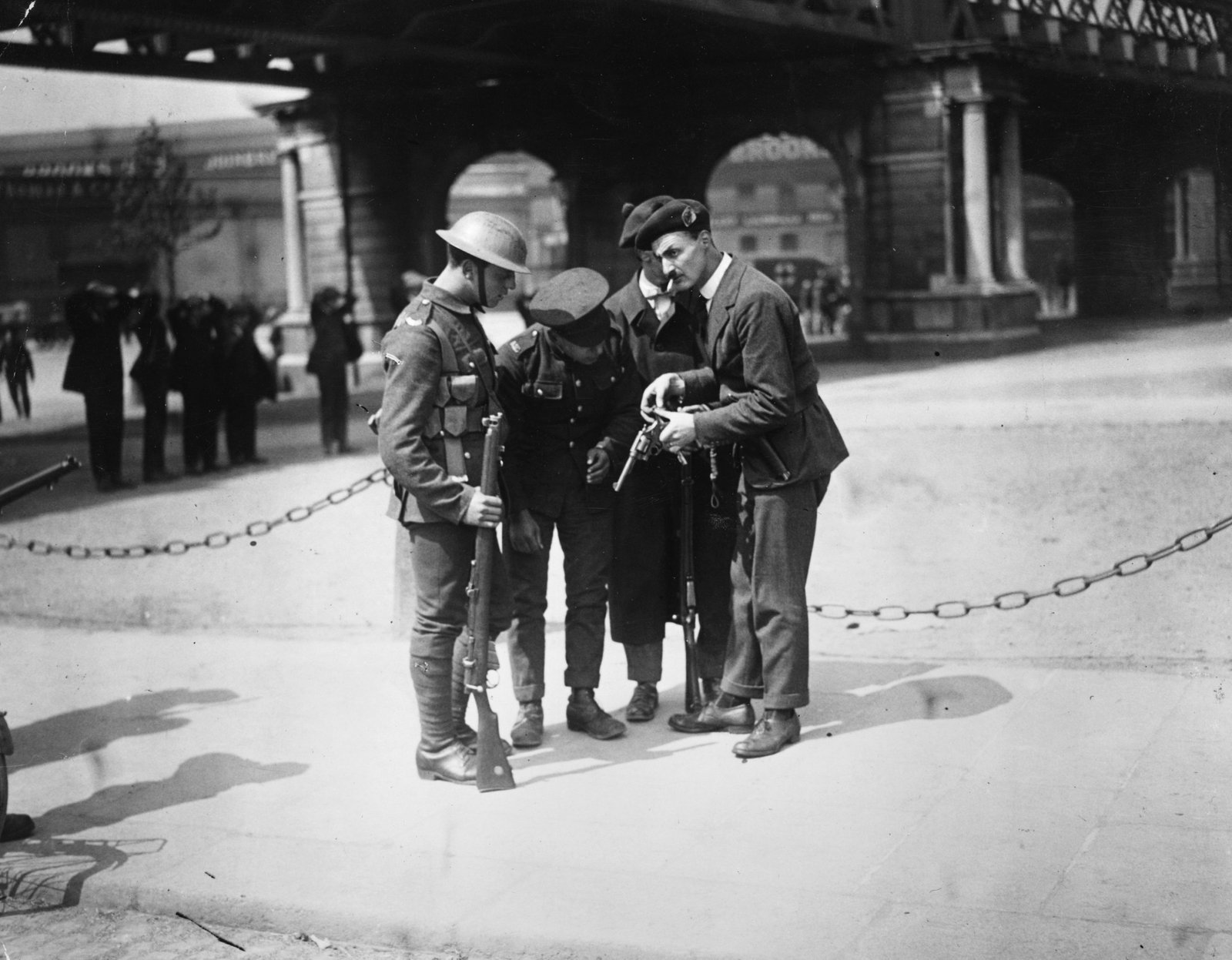

British soldiers watch a Black and Tan reload his revolver outside the Custom House. Photo: Walshe/Getty Images

The Auxiliaries soon arrived. As the fire began to take hold, panic set in amongst the crowd. Calls flooded into the city's fire stations from worried civilians. All calls were answered and the people were reassured that help was on the way. But no help was coming; the fire stations were in the hands of the IRA.

With every round of ammunition spent, the order to evacuate was given. They were ordered to dump arms and mix in with the crowd. The majority did this; others decided to take their chance and try to escape.

Casualties of war

Traynor and Captain Paddy Daly were observing the situation outside when they came under fire from the military. Volunteer Dan Head threw a bomb at the lorry, saving Traynor and Daly. Head was shot and killed, he was eighteen years old. Ennis was the last to leave the burning building. He made a dash from a side gate to a laneway opposite. He was hit twice, but managed to get to safety.

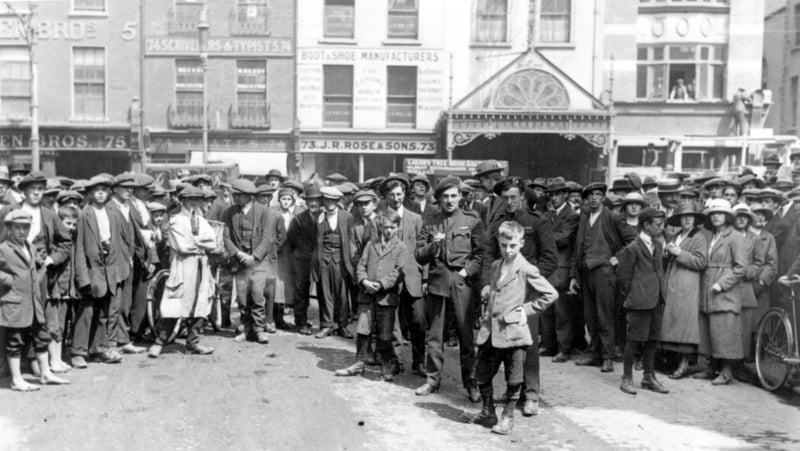

Those who had mixed with the staff were gathered outside. Each staff member was identified and led away; those left were searched by the military and questioned.

A man lies dead on Beresford Place after the IRA attack on the Custom House. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland. NLI INDH 90

Against a backdrop of the Custom House engulfed in fire, those who were in custody were taken away. Most were brought to Arbour Hill, others were taken to Mountjoy Gaol and Dublin Castle, as Christopher Fitzsimons remembered in his Witness Statement:

We were segregated on the quayside and taken to Dublin Castle. We were interrogated at the Castle for three days and suffered pretty severe handling from the Auxiliaries.

IRA prisoners in Beresford Place. Image courtesy of Liz GIllis

After some weeks the majority were transferred to Kilmainham Gaol.

Despite their losses, five dead and over 100 captured, and many guns lost, the Dublin Brigade carried on the fight in the days and weeks that followed, when they launched several attacks on the Crown forces.

International attention

News of the day's events raced around the world, focusing, as De Valera intended, international attention on what was happening in Ireland. Some, seeing the losses suffered by the IRA, said the operation was a failure. Others, including those who took part, saw beyond that to the crippling blow that had been delivered to the British Administration in Ireland.

Thousands of records essential for running the country were lost. The success of destroying such documents was not just down to the IRA but also the Dublin Fire Brigade. It was their task to try to save the building. However they did the complete opposite.

Michael Rogers, Fireman and IRA man, recalled in an interview with the Irish Press that on entering the Custom House, he and others had the building at their mercy and actually worked to spread the fire throughout the building. The Custom House burned for days.

Dublin Fire Brigade men remove the wounded after the IRA attack on the Custom House, Dublin. The armed men are Auxiliaries. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Sadly nine people died, five Volunteers and four civilians. It was never the intention that anyone should die that day. They were, Volunteers Dan Head, Sean Doyle, the brothers Patrick and Stephen O'Reilly and Edward Dorrins. The civilians killed were John Byrne, James Connolly, caretaker Francis Davis and Mahon Lawless.

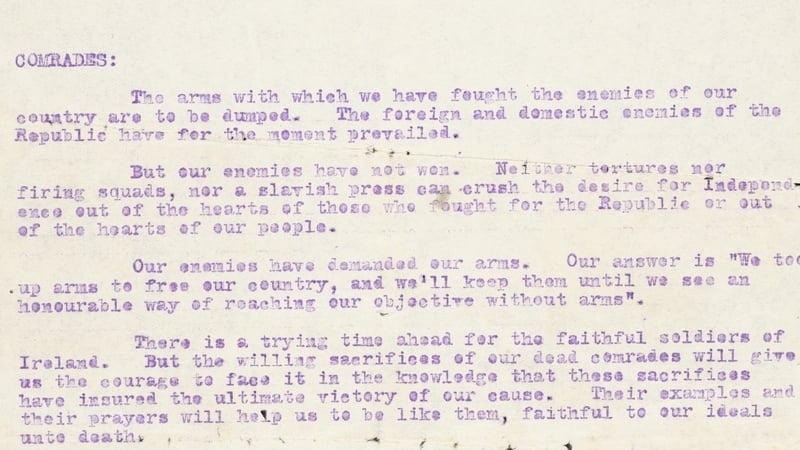

Later, many claims were made that the operation was a disaster, and the IRA was wiped out; that is not the case. The aim of this operation was to bring international attention on Ireland; that happened. It was carried out to make Ireland ungovernable; that was achieved.

Most importantly, with their ranks depleted and having lost a number of weapons, the IRA quickly adapted their tactics and continued the war, thus calling the bluff of the British government, and within weeks negotiations to end hostilities began.

The ruins of the Custom House. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

This article is part of the War of Independence project coordinated by UCC and based on The Atlas of the Irish Revolution edited by John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil and Mike Murphy and John Borgonovo. Its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.