Analysis: Ireland's first ever attribution study has unpicked the causes of the Co Cork town's Storm Babet flooding and its possible links to climate change

By Ben Clarke, Imperial College London and Peter Thorne, Maynooth University

In mid-October 2023, Storm Babet brought devastating rainfall to southern Ireland. Over two days, more than 100mm of rainfall fell in Midleton, Co Cork - the equivalent of a month's worth of rainfall in the town. The rain fell on soils that were already saturated by an extremely wet late summer and early autumn. Swollen rivers burst their banks in Midleton. Around 400 homes and 300 businesses were flooded, with damages estimated at nearly €200m.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Morning Ireland, RTÉ Southern Editor Paschal Sheehy reports on flooding in Middleton, Co. Cork where homes and businesses have been deasted by Storm Babet

In the aftermath of storms like Babet, many people often ask the question: 'is climate change to blame?' Around 20 years ago, scientists struggled to provide a detailed answer. But, today, thanks to attribution science, we can.

Climate change's fingerprints on extreme weather

Extreme weather events are one of the clearest symptoms of climate change. Record-breaking heat waves, fires, storms and droughts put a tangible and violent face on a sometimes seemingly ephemeral phenomenon.

Since the Industrial Revolution, emissions from the burning of oil, gas and coal have accumulated in the atmosphere, causing Earth's atmosphere to warm by about 1.2°C. Warming of 1.2°C might not sound like much to some people, but this warming is making weather events more intense around the world.

Using weather data and climate models, attribution science uncovers how climate change influences the individual extreme weather events. While attribution studies don’t tell us whether an event was 'caused by’ climate change, they do tell us how the likelihood and intensity of events like it have changed as a result.

For example, in December 2015, Storm Desmond brought severe rain and flooding to Northern England and southern Scotland. Scientists found that events similar to it had become around 60% more likely due to human-induced global warming (at the time it occurred - this has now likely increased again with further warming since 2015).

Findings like these help us understand how the weather is changing and plan for the future. The studies can also motivate global efforts to reduce emissions. Attribution science shows us that climate change is already happening, making life more dangerous and more expensive for billions of people.

Over the past two decades, attribution scientists have studied hundreds of extreme events around the world. The methods are now well and truly tried and tested. World Weather Attribution, an international team of climate scientists, are leading the charge. They have published more than 60 studies on extreme weather events since 2015.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime in June 2023, Prof Peter Thorne assesses the findings of the latest IPCC report

Some extreme weather events are unaffected or weakened by climate change. For others it’s hard to say. But for many, the result is that climate change is making things worse. The evidence is so compelling that the latest Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change report concluded that "human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe."

Storm Babet: Ireland’s first attribution study

In early February, a team of scientists from Met Éireann, Maynooth University and World Weather Attribution met in Maynooth to study Storm Babet. It was Ireland’s first-ever attribution study using modern techniques developed by World Weather Attribution.

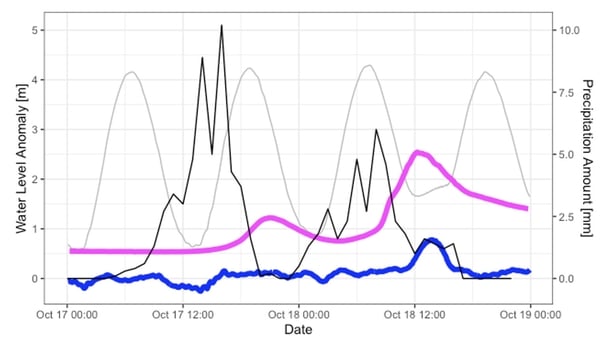

The analysis aimed to unpick the causes of the severe flooding in Midleton and its possible links to climate change. This featured several stages. First, we studied tide and river gauges. This showed us two crucial pieces of information: that there was no storm surge flooding that was blown from the sea, meaning the flooding was driven by water from burst rivers.

We also found that the river flooding coincided with a spring low tide. This meant that flood waters were able to drain into the sea incredibly efficiently. However, had the river flooding occurred during mid or high tide, or even worse with a storm surge on top, drainage would have happened much slower, meaning the flooding would have been even more destructive.

Second, hydrological models of the river basins around Midleton showed that over the years, high river levels are often driven by pulses of rainfall similar to those dropped by Babet, especially when soils were already saturated. This finding meant we were confident that rainfall was the main driver of the flooding

The verdict: did climate change play a role in Midleton?

The final part of the study was to investigate how climate change influenced the extreme rainfall.

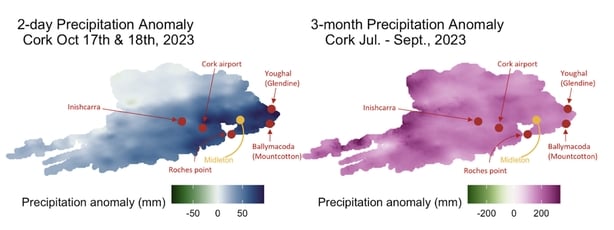

We looked at two separate types of rainfall in Co Cork: the wettest two days of rainfall in October to investigate rain that causes flooding events and rainfall from July to September to investigate rain that causes saturated soils and worsens flooding events

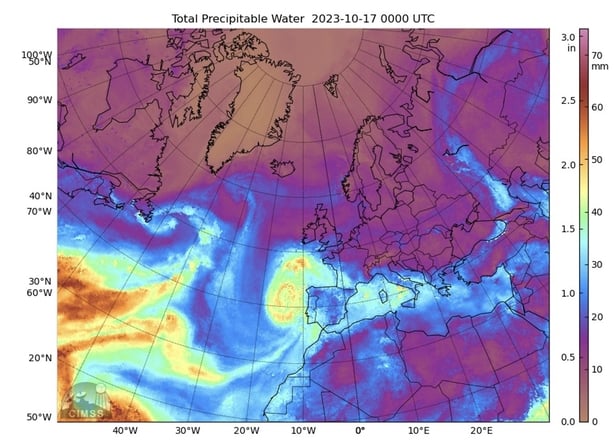

At the beginning of the study, we had various expectations. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, resulting in heavier rainfall. Other attribution studies on events in the UK and northern Europe have often found that climate change increased the intensity of heavy rainfall by around 5-10%.

The longer-term rainfall is more complex. The amount of rain in the July to September period depends on the position of the jet stream and other atmospheric circulation patterns. This is more challenging to model and changes in these large-scale patterns over time and due to climate change are highly uncertain.

After analysing decades of weather data and climate models, we found that extreme October rainfall has become about twice as likely and 13% more intense in County Cork. We also found that heavy rainfall will occur more often and become more intense as the climate warms further.

As expected, our analysis of rain in the July-September period was more complicated. Real-world weather data suggests that this period is becoming a little wetter as the climate warms. However, climate models suggest that this period will become drier in the future. The disagreement meant we couldn't determine how climate change might be influencing this rainfall.

A better or a wetter future?

The results of our study indicate that heavy rainfall is becoming more intense in southwestern Ireland. At a global level, the finding reiterates what we already know: as long as humans fill the atmosphere with emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, extreme weather events will become more intense, highlighting why we urgently need to replace fossil fuels with cleaner, renewable sources of energy.

At a local level, our finding outlines the challenges southwestern Ireland will face in a warmer, wetter climate. In October, a low tide made flooding much less severe in Midleton - the town dodged a proverbial bullet.

However, in the future, storms like Babet could arrive during high tide, causing more intense flooding and much costlier damages. It is clear southwestern Ireland needs to prepare. Flood protection and relief schemes, insurance for vulnerable communities, and considering the growing risk of floods in development will be crucial to weather future events like Storm Babet as the climate warms.

A RTÉ Prime Time report will examine new research on how climate change magnified Storm Babet's impact on Midleton. Watch in full tonight at 9.35pm on RTÉ One and RTE Player

Follow the RTÉ Brainstorm WhatsApp channel for more stories and updates

Dr Ben Clarke is a Research Assistant in the Analysis and Interpretation of Climate Data for Extreme Weather at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College London. He works on understanding the influence of climate change on extreme weather events, as part of the World Weather Attribution project. Prof. Peter Thorne is a Professor in Physical Geography (Climate Change) and Director of the Irish Climate Analysis and Research UnitS group (ICARUS) at Maynooth University.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ