For Aristotle, the art of comedy was about more than just soliciting laughs. Its job, he said, was to track the fortunate rise of a sympathetic character, and to treat the base or ugly elements of life with a lightness of touch that would generate empathy.

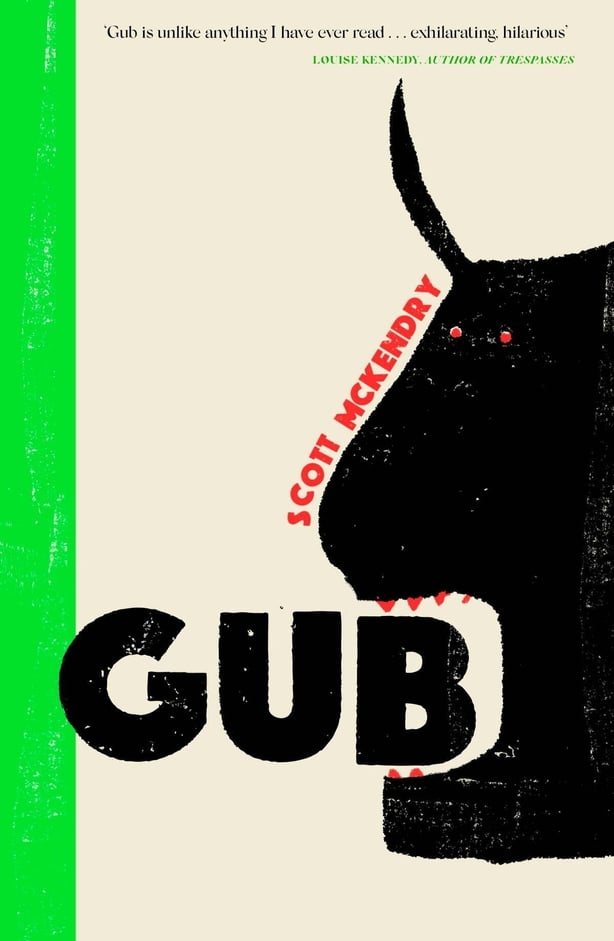

Most writers work years to achieve this kind of balance. For a rare few, life's absurdity pervades almost everything they do and their wit becomes almost as purely identifiable - as natural to their makeup - as an organ or a limb. If there’s one contemporary poet for whom this rings truer than the rest it’s Scott McKendry, whose debut poetry collection Gub is already being hailed as 'the most exciting… to come out of the north of Ireland in many years.’

For the avoidance of doubt, that's Louise Kennedy’s opinion, not mine; a writer who - if she is known for anything other than her own exceptional body of work - must surely be known for not mincing her words.

What’s surprising, then, isn’t that McKendry’s work is deserving of such praise - for indeed it is - but that it hasn’t yet been posted to every household across the island of Ireland. For if it was, in the manner of the Good Friday Agreement, the class issues that unite us would seem so comically self-evident as to nullify many of society’s lingering quarrels about nationhood.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen: Scott McKendry talks to RTÉ Arena

Nor does McKendry gloss over these issues. In fact, poems like ‘Five Zillion Geese’, ‘At the Convention’ and ‘Fiesta’ tackle the thorny subjects of poverty, sectarianism, contemporary loyalism and paramilitary violence head-on, and do so in such a way as to emphasise the ordinary bathos inherent in the everyday.

Each one of these poems is a black comedy in miniature. An episode in the life of Aristotle’s archetypal ‘sympathetic character’, which in this case seems to be McKendry himself, or his occasional alter-ego Monsieur Forgèt.

‘Five Zillion Geese’ recounts the story of how a migrating flock of greylag geese was given protection by a loyalist paramilitary group operating in the Hammer area off Belfast’s Shankill Road. ‘At the Convention’ imagines two semi-retired enemy combatants - one Republican, one Loyalist - breaking bread at a BBQ they are bound to by the marriage of their younger relatives. And ‘Fiesta’, which tells the story of how a family’s only vehicular mode of transport is commandeered by a group of local heavies wearing balaclavas and carrying guns.

McKendry’s surreal mode of address in these poems can’t help but call to mind other documentarians of the Irish absurd; not least Ian Duhig, with whom he shares an often humorous fascination with mythology and the Occult. Or his mentor Ciaran Carson, whose slippery analyses of the vernacular borders that characterise speech are present in McKendry’s own phonetic rendering of what he calls Belfastois.

But it’s the influence of John Berryman which really shines through, influencing everything from the periodic interjections of McKendry’s alter-ego to the deft tonal shifts from high comedy to high tragedy, often in the space of a single line or sentence. "As an expendable character in the comedy of your life," he writes in ‘All I want is my Goose Back’. "I wonder why I// annoy myself about your feelings."

In one touching elegy to a lost friend, ‘Ain’t Mississippi’ captures the complexities and vicissitudes of male friendship and group dynamics, which so often is characterised by a heady mixture of testing one another’s limits and tender fraternity. Set during the all-too-familiar bonding ritual of a lads’ holiday, the poem sets its subject up as the beautiful punchline to a lost yarn; the comic relief - though never the butt of the joke - who nevertheless is the clear and shining centre around which the poem’s friend group gravitates.

'That did it. We laughed all night,

baffled about why you’d lied

but loving your yarns. And now you’re dead

I understand that piety

to things that happened, to how they exactly happened, is the start of pain

and the death of art.'

Gub then is an original, surreal, acerbic, funny masterpiece. A welcome addition into the annals of Irish letters, which too often forgets that good comedy often makes us cry as well as laugh. ‘Anyway…’ as the book’s epigraph baldly instructs. Now is the time to pick it up and read for yourself.

Gub is published by Corsair