The shadow of the Gaelic Revival in Irish literature is long and occasionally dimming. Figures like Yeats are too often invoked to promote a kind of safe, mystical version of Ireland; one in which its simple inhabitants tell fairy stories to one another, dreaming visions of a past which by and large never existed.

If anyone is aware of these pitfalls it’s Warrigton-born Irish poet and lecturer Seán Hewitt, whose specialist academic interest—among other things—is the role that politics and nature play in the works of influential playwright John Millington Synge. Like Synge, Hewitt is something of a polymath, and like Synge his body of work carefully subverts the entangled orthodoxies that too often define our national body of literature.

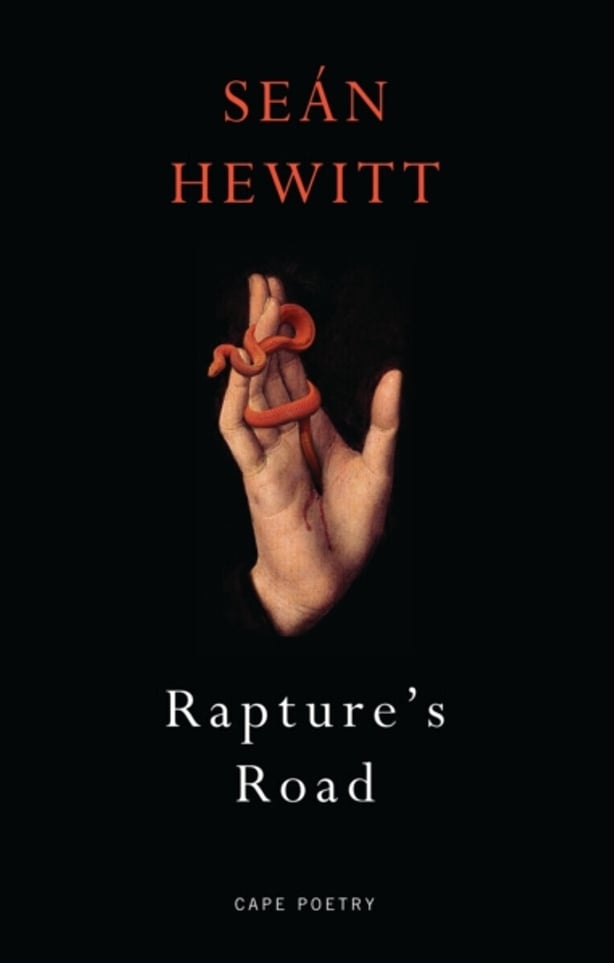

Unlike Synge, however, Hewitt is sceptical of the role of self-anointed perspective, and nowhere is this clearer than in his sophisticated, androgynous and multi-faceted second book of poems Rapture’s Road. Though the collection takes its title from Indian-American poet Agha Shahid Ali’s Tonight - a ghazal emblematic of the New Formalism movement with which he identified - Hewitt’s approach to form is both controlled and playful. Demonstrative of a voice which is confident enough in its mastery of poetry’s strictures that he knows exactly when to submit and when and how to rebel against it.

Form for Hewitt seems more to do with rhythm and sonic texture than discipline. In Go to the lamplight… for example, he employs the same kind of deceptively beautiful nursery rhyme cadence as Sylvia Plath’s Daddy, making the words all the more insistent and memorable, driving towards their reader like a train: ‘Go to the lamplight / Go to the empty ring-road in its sleep / Go to the gates, go through / Go in the dew with your wet shoes / to the river.’

In the opening poem A Ministry this approach manifests as a subtle interplay between Romantic yearning and wry self-awareness. ‘… each night / I play both sinner and priest – ’ he writes. ‘assigning prayers, the dog-collar, / the dove, the blister of thorns.’ There is an acknowledged debt in these lines, of course, to the more mystical bent of the Gaelic Revivalists with whom Hewitt is so familiar—George Russell (better known as Æ) in all his pomp manifesting dream visions and prophecies from the natural landscape; the High Priest Yeats at the height of his Golden Dawn experimentalism, calling forth spirits to assist him in the practice of ‘automatic writing’.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen: Sean Hewitt talks to RTÉ Arena

But for every calling back, there is also something thoroughly modern and grounded about Hewitt's approach. The fluidity of voices he employs - far removed from the lonely-man screeds of the male Romantics - is more akin to someone like Mark Doty or Louise Glück.

Hewitt is unafraid to write from the perspective of the non-human, if only to emphasise that these poems are mortal; hyper-aware of the bargain that we have made with nature, which is to apprehend its beauty we must forego any idea of permanence.

In one exceptional act of ventriloquism, We Didn't Mean to Kill Mr Flynn draws on court testimony, newspaper archives and academic monographs to reconfigure the voices of both murderer and murdered in the tale of perhaps the most infamous homophobic murder in Irish history; that of Declan Flynn in Fairview Park, Dublin in 1982. Indeed, while nature for Hewitt offers possibility and freedom to explore queer identity away from the judgement and preconceptions of "polite" society, poems like these serve as stark reminders that completely safe spaces still do not exist for LGBTQI+ people.

One cannot help but think about the recent case of Brianna Ghey in England - a 16 year-old transgender girl who was murdered by two teenagers in Culceth Linear Park, not far from Hewitt’s native Warrington. It is a painful reminder of the excruciating legacy of violence that queer people have to endure, though it is treated with delicacy and compassion above all else in Hewitt’s extraordinary sequence.

On the whole, Hewitt’s Rapture's Road is that rare thing when it comes to second collections. Something which takes his debut Tongues of Fire’s natural elements and post-modern Romantic themes and fashions them into something wholly unique. Rapture’s Road is political without being hectoring, mystical without being detached, and wholly in hoc to a natural world in all its chaos, beauty, creativity and destruction.

Rapture's Road is published by Jonathan Cape