The Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts (RHA) was founded in Dublin by Royal Charter in 1823.

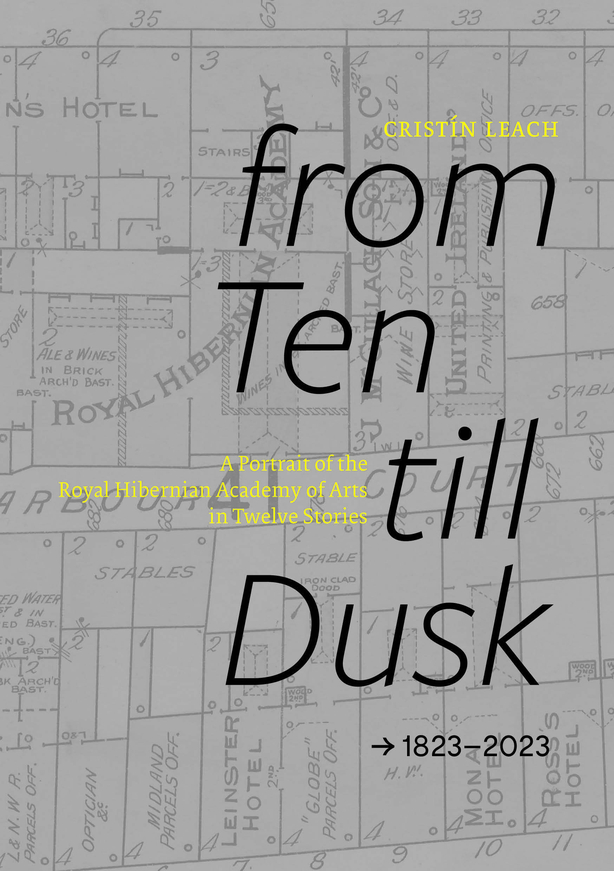

In 2023, the academy celebrated its 200th anniversary with a series of exhibitions and events, including the publication of a new book by author and critic Cristín Leach, From Ten till Dusk, A Portrait of the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts in Twelve Stories, published to mark the bicentenary.

The book, with design by Oonagh Young, is a multiform narrative anchored around twelve key years in the RHA's history, beginning in 1826 and ending in 2018.

This extract is from the chapter entitled There is a Man, a lyric essay anchored in the year 1985.

architect Arthur Gibney PRHA (1933-2006)

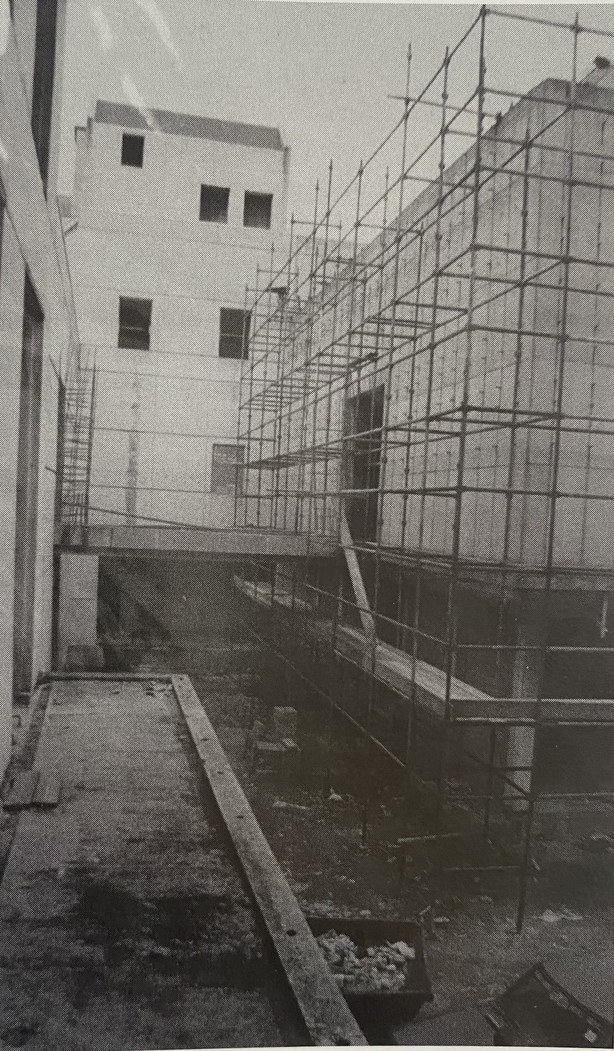

Photo: RHA Archives

There is a Man (1985)

THERE IS A MAN climbing through the hoarding that covers the outside of the unfinished building at 15 Ely Place. His name is Patrick Murphy, and he is finding a way in so he can look at the spaces inside. It’s 1980, ’82 or ’84, and the building is a concrete shell. Murphy is the exhibitions officer for the Arts Council of Ireland. Twenty, 30, 40 years from now he will walk into the finished gallery to work every day as the first appointed director of the Royal Hibernian Academy. He is curious about the vacant, halted structure, its concrete foundation first poured in 1972, on a site bought by the Academy in 1939. The place is a building site, now sealed up. Since a fire destroyed Academy House in 1916, the RHA has wandered across the city, holding its annual exhibition from 1917 to 1984 in borrowed and loaned venues: the Dublin Metropolitan School – then National College – of Art on Kildare Street; the Royal Dublin Society in Ballsbridge; Dublin Castle; and the National Gallery of Ireland on Merrion Square.

THERE IS AN ART CRITIC who writes in The Irish Times on the last day of 1970 that the Academy’s new building is finally on its way: 'we should have a modern art gallery in Dublin by the summer of 1972’. He’s wrong. He writes that Dublin has been badly in need of ‘a proper exhibition hall’ for its big annual exhibitions, including the RHA Annual Exhibition, the Living Art Exhibition, the Oireachtas Exhibition and, since 1969, the Independent Artists. He’s right. He says the shows held by the Academy and the Living Art at the College of Art have ‘begun to look tattier and tattier’ as the years have gone on. He writes of the Rosc international art exhibition held in 1967 ‘in the vast hall of the RDS.’, and of the ‘biggest visiting shows’ held at the Municipal Gallery on Parnell Square: Art USA Now, and a Francis Bacon retrospective. He writes that ‘Mr. Haughey put the State reception rooms in Dublin Castle at the RHA’s disposal for its 1970 exhibition.’ He observes that ‘The Municipal, lying as it does a little north of O’Connell Bridge, is just a fraction too far away to be part of the much-discussed "cultural complex"’, with its National Gallery, National Library, College of Art, two universities and two museums, all on the other side of the river. But the Municipal Gallery is ‘the only important cultural centre north of the Liffey, and the fashionable south side should not be allowed to take away the play from it completely.’ He believes ‘The strategic situation of the new gallery will in fact be one of its greatest advantages.’ The critic’s name is Brian Fallon.

THERE IS AN ARCHITECTURAL CORRESPONDENT who writes in an article on the same page as Fallon’s that ‘perhaps the most satisfactory aspect of the project is that it opposes the trend created by office development of creating large areas of the central city which are lifeless after 6p.m.’ His name is Kenneth Madden.

Photo: RHA Archives

THERE IS A BUILDER who proposed in 1969 that he would build and pay completely for the construction of a gallery and administrative building for the RHA on the Ely Place site. It would be owned and administered completely by the RHA. Commentators describe this as ‘an extraordinary move’, ‘a magnanimous gesture’, ‘a generous benefaction’, and ‘a gift to the nation’. The builder’s name is Matthew Gallagher.

THERE IS AN ARCHITECT and a member of the Academy who will be president in 1977. He draws the design and completes the plans for the proposed building. Along with several galleries, he includes six studios on the top floor, all with true north light only. He adds keeper’s apartments, a caretaker’s flat, storage space, a reception area, and car parking for 25 cars. The building is to be air-conditioned throughout, to give Dublin a venue for exhibitions requiring climate control, which the city does not currently have. The architect’s name is Raymond McGrath RHA.

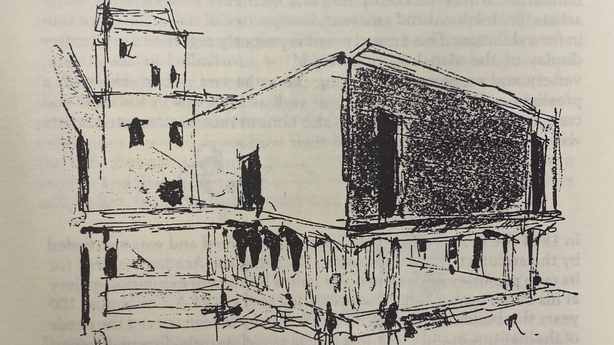

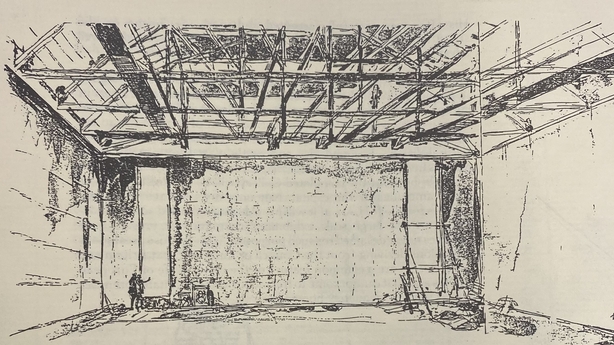

constructed RHA Gallagher Gallery, designed by

Raymond McGrath (1903-1977) PPRHA

Pic: RHA Archive

THERE IS A POLITICIAN whose name is Charles J. Haughey. He will be Taoiseach from 1979 to 1981, in 1982 from March to December, and from 1987 to 1992. A Minister for Social Welfare, Health, Finance, Agriculture, Justice, and the Gaeltacht. Leader of his political party Fianna Fáil from 1979 to 1992.

THERE IS A MILLIONAIRE BUSINESSMAN, a self-made entrepreneur. He has known Charles Haughey since the late 1950s, he donates to Fianna Fáil, and is a supporter of this ambitious politician who lives an extraordinarily extravagant lifestyle. His companies' accounts are handled by a firm in which Haughey is a sleeping partner. He employs Haughey’s brother as an engineer. It is with Haughey’s prompting that he decides to fully fund the building of a headquarters for the RHA at Ely Place. The move is hailed as a perfect echo of the gesture made by architect and former RHA President Francis Johnston when he designed, built and gifted the Academy its first home on Lower Abbey Street in 1824. The millionaire businessman is the builder whose name is Matthew Gallagher.

of partially constructed RHA Gallagher Gallery

Pic: RHA Archive

THERE IS AN ARTIST known for his beach paintings who died in 1984. In 1985, the RHA decides to hold its 156th annual exhibition in the still unfinished building at Ely Place. It will run from 20th June to 28th July. The site is roofed, structurally sound, dry, and deemed 70 per cent complete. It has been cleared of debris and building materials. As is tradition, the exhibition honours any members who died in the previous year. The colour illustration on the cover of the catalogue is a summer beach composition called The Bathers, by the late artist who painted beaches and died the previous year; his name is H. Robertson Craig RHA.

THERE IS A WOMAN, the only one among the 25 self-selected academicians of the RHA in 1985. She is a sculptor whose name is listed in the catalogue for the 156th exhibition. Her name is Carolyn Mulholland RHA. Her terracotta Humming Head is featured in the catalogue, reproduced in black and white. They have spelled her name wrong in the caption, Caroline instead of Carolyn. Next to it, on the same page, is a bronze sculpture by Imogen Stuart ARHA called The Saint. The ten associate members listed are John Behan, Pauline Bewick, Basil Blackshaw, Noel de Chenu, Conor Fallon, Marjorie Fitzgibbon, Kevin Fox, Domhnall O’Murchadha, Imogen Stuart and Barbara Warren. The honorary members are listed too. There are 19 names including that of the Fianna Fáil politician Charles J. Haughey TD.

THERE IS A PAINTER. His name is Thomas Ryan. He is the 18th President of the RHA. A painting by him is the first artwork listed in the 1985 exhibition: 1. The Palm House, oil, price £880. This year, he is selling £1 raffle tickets to win one of his paintings, hosting a £5 white-and-red-wine President's Reception, and appealing for subscribers, donors, friends, sponsors, and benefactors, in fliers and pamphlets published 'in aid of the RHA Building Fund.’ Ryan writes in the Irish Arts Review, under the headline THE VICISSITUDES OF THE RHA, that ‘During the student unrest in the late 1960s, the College of Art was infected’ causing the RHA exhibition to lose its home there. He writes that ‘The building was well advanced when Matthew Gallagher died in 1974.’ He writes, ‘As a consequence of his death the Gallagher Group was subjected to internal difficulties … When the Gallagher Group collapsed in 1981, the RHA repossessed themselves of the incomplete building.’ Ryan quotes the art historian and director of the National Gallery of Ireland from 1915-16, Walter G. Strickland: ‘Whatever may have been the shortcomings of the Academy either as a Society of Artists or a teaching school, it must be recognised that its extinction would be a calamity.’ And he writes that there has been record public attendance at the 1985 exhibition.

THERE IS A JOURNALIST and former editor of The Irish Times whose reporting concurs. His name is Fergus Pyle. He writes in The Irish Times in June 1985, under the headline RHA LAUNCHES £1.2M APPEAL FOR GALLERY, ‘The building itself was what most of last night’s guests, who at times extended for hundreds of yards down Ely Place as they queued to get into the exhibition, came to see. Even in its unfinished state it is an impressive addition to Dublin’s galleries.’ He writes that the opening was ‘literati-drenched’, and quotes Ryan in his urgent appeal for money: ‘First of all, we would look to the State for some public acknowledgement of the worth, scale and munificence of Mr Gallagher’s endowment.’ He writes that the President of Ireland, Patrick Hillery, and his wife were ‘among the guests who last night struggled for a glimpse of the 460 pictures in the exhibition’.

Ryan is tirelessly pushing for funds. In a pamphlet printed in black ink on thin, cream-coloured paper under the title ‘The Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts Notice to Appeal’, he writes, ‘Almost every Irish artist of distinction, living or dead, has been a member or associate of the RHA’. He writes, ‘For almost 112 years the Academy provided training for young artists in its Academy schools. These schools closed in 1938, but it is the intention of the RHA to re-open them.’ He writes, ‘In 160 years of existence the RHA has never sought public assistance, now, in the belief that its purpose is to the common good of the nation it hopes to make an appeal for funds to complete the Gallery. The sum required for this purpose is approximately £1million (the cost of an average village primary school).’

THERE IS A JOURNALIST who points out that the money the Academy needs is likely much more than that. It’s Brian Fallon again. He writes on Wednesday 29th May in anticipation of the 1985 annual exhibition, ‘The Royal Hibernian Academy will be holding its annual exhibition in the (so-called) Gallagher Gallery next month, and apparently the building remains in the same state as it did when the Guinness Peat Aviation awards exhibition was held there last year.’ He writes, ‘When originally planned, the Gallagher Gallery was to cost a quarter of a million pounds, no mean sum at the time, but today its completion alone would need several times that. Estimates for this have varied from half a million to a million and a half, but I suspect that two million would be nearer to the mark.’ He writes, if the RHA ‘thinks that the necessary funds can be raised by art sales or collection boxes, then it is pipe-dreaming in opaque clouds of smoke.’ Fallon writes that the gallery could be like the Hayward Gallery in London, ‘a specifically designed modern gallery of art to equal any in Europe.’ He writes that it ‘can hardly remain as a concrete hulk in the middle of Dublin for the next two decades… Diplomacy on a high level, of a high level, is called for and it must be put in train before another year is out and the RHA faces yet another exhibition open to wind and weather.’

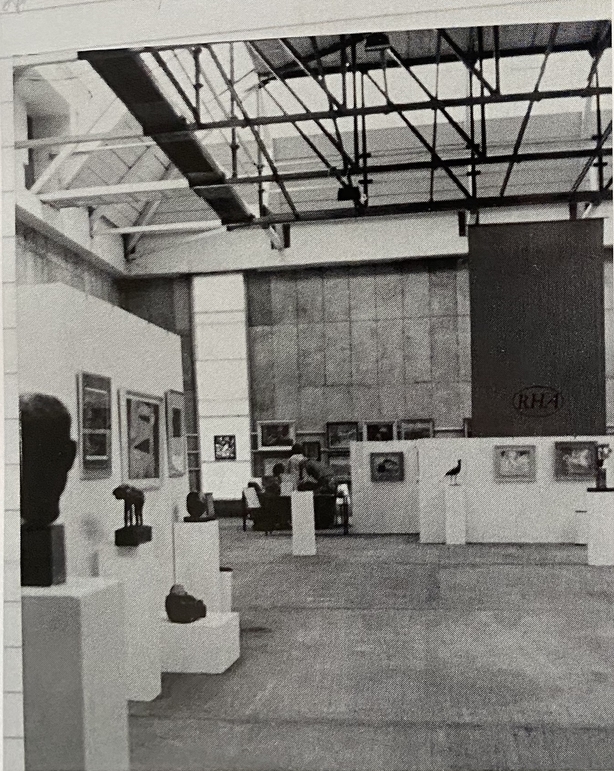

Photo: RHA Archives

THERE IS A WIDOW who worked as a nurse in Switzerland during World War I, a Polish woman who married an Irish solicitor and antiquarian book collector from County Kildare called Barry Brown. On her death in 1979, she leaves a considerable fortune in her will to be administered by her executors. Her name is Wanda Petronella Brown.

THERE IS A LIBRARIAN, a retired former director of the National Library of Ireland and the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art in Dublin who was friends with Wanda’s husband Barry. In 1985, he applies to the executors of Wanda’s will and is granted substantial funding from the bequest for cultural bodies including the National Library of Ireland, the Palestrina Choir of St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, and the Royal Hibernian Academy. For the RHA, he secures £200,000. His name is Patrick Henchy. There is an executor of the last will of Wanda Petronella Brown, who makes these allocations. His name is Zbigniew Skutnicki.

THERE IS AN ART CRITIC. His name is Desmond MacAvock. He reviews the 1985 RHA exhibition for The Irish Times, noting that although the floor, walls, stairs and ceiling remain unfinished, the building is spacious, and the lighting system is installed. He doesn’t think the quality of work has improved, or disimproved, on previous years. He notes the display of paintings of the ESB Shannon Scheme by the late former RHA President Seán Keating. By 1985, ongoing discussion about the unfinished gallery is getting tired. The art critic Brian Fallon writes in The Irish Times, ‘What is potentially one of the finest galleries in these islands, looks like remaining a concrete shell for an indefinite period. I have been writing about this subject for roughly a decade and a half and do not propose to return to it in the near future.’ The RHA was already looking to move to the other side of the Liffey when the fire of 1916 made the decision for the Academy and its members. The once planned and envisaged gallery district of the 1800s on Lower Abbey Street has never materialised. Visitors complained the rooms were dark, even though the drapery had been removed.

THERE IS A JOURNALIST writing in The Freeman’s Journal on Saturday 16th Dec 1916, eight months after the Rising. ‘Contending with difficulties of various kinds, and not least of all the drifting away of fashionable folk to other quarters, which left the house in Abbey street often unvisited, the Hibernian Academy has made a brave show each Spring, when its doors opened for the season. It has been the scene of several brilliant gatherings, and whoever entered its precincts felt gratified that it existed. The removal of the Academy to a different part of the city has been suggested from time to time, and now that the entire fabric, with, alas! its entire contents, for, as it happened, a specially nice collection had been gathered together, has fallen a victim in the destruction, the opportunity offers for establishing a new Academy House in a more favoured locality.’ That journalist remains anonymous.

THERE IS ANOTHER JOURNALIST. His name is Paddy Clancy. On Sunday 6th November 1988, in The Sunday Independent, he writes that the gallery is finally finished. ‘A MAJOR GALLERY of the arts was opened last night to the public – 10 years after its construction was halted when funds ran out following the death of its main benefactor, millionaire builder Matt Gallagher.’ He writes that ‘An estimated £1.5 million went into phase two of the project – resuming the work, which ended with Mr Gallagher’s death, and the subsequent financial difficulties of companies connected with his family.’

THERE IS ANOTHER ARCHITECT and RHA member and future RHA President, who provides the final design. He went to school with Charles J. Haughey and the two were lifelong friends. He’s the man who designs Haughey’s Christmas cards. That man’s name is Arthur Gibney RHA.

Photo: Irish Architectural Archive Photographic Collections

THERE IS A VICTORIAN MOCK TUDOR HOUSE at 15 Ely Place, built in 1897 by the architect and RHA member Sir Thomas Manly Deane. At first, it is his residence, then also for a time his architectural office. Deane exhibits with the RHA from 1890 to 1914. In 1908 he sells his home to a writer and surgeon who wants to buy a house opposite his friend, the writer George Moore. That man’s name is Oliver St John Gogarty. The house at Ely Place hosts a regular literary salon. In 1939 Gogarty, a man with a life marked by flamboyancy, politics, a kidnapping, libel suits, and a falling out with the writer James Joyce of inescapable literary impact, is off to New York. The RHA under President Dermod O’Brien buys 15 Ely Place, and an adjacent garden belonging to Moore, using the government insurance money from the fire of 1916. O’Brien plans to build a gallery in the garden, eventually. In the 1950s, Dublin Corporation attempts to turn the site into a carpark. It will not fulfil its purpose for another 45 years.

THERE IS A BUILDING on Ely Place, where number 15 once stood, built of reinforced concrete, with foundations poured in 1972. In 1985 it opens its doors, unfinished and appealing for funds for completion. In the end, the money comes thus: £75,000 from the RHA; £200,000 from Wanda Petronella Browne’s estate; £250,000 from Charles Gallagher, Matt Gallagher’s brother; £250,000 from the National Lottery fund; £100,000 from the Government Funds of Suitors, a nest-egg of unclaimed money from court settlements and the people who die intestate; a collection of smaller private donations; and bank loans. The name of this building will ultimately be the Royal Hibernian Academy Gallagher Gallery.

From Ten till Dusk, A Portrait of the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts in 12 Stories is out now - listen to the accompanying audio series here.