'I was amazed when I came to read The Fly on the Wheel that so many of my own impulses growing up were echoed in Katherine Cecil Thurston's turn-of-the-century Waterford.'

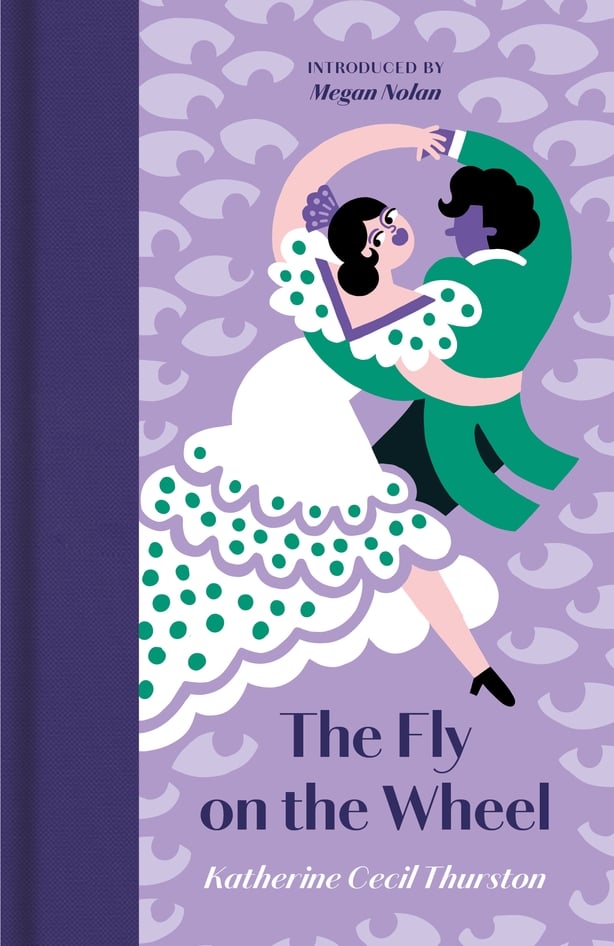

Acclaimed author Megan Nolan introduces the new edition of the vintage bestseller by rediscovered Irish author Katherine Cecil Thurston, a moving story of illicit love first published in 1908 and now re-issued in a new edition, published by Mandalay Press with illustrations by Fatti Burke.

Like many people, I spent my youth scheming about how to escape the place where I grew up, before entering adult life where I spend much of my time fantasising about how to return to it – in essence if not in material reality. The defning feeling of my adolescence in Waterford was a sort of productive boredom, fruitful frustration about the inaccessibility of what I considered to be real life, which was so out of reach despite its proximity. My time was spent with like-minded fellow dreamers – including Kathi Burke, the illustrator of this book – with whom I conceived little projects and half-completed creative endeavours which felt as though they were bringing us closer to where we needed to be. We lived in a romantic dichotomy of loving Waterford ardently – its uniquely hilarious people and winding streets, its bodies of water and woods – and needing to leave it to feel realised

I often think of this feeling which plagued me then, that we were not the real, true people of the world, and our hometown was not the real true place of the world. To me, the real people, those living an authentic rendition of life, were in large bustling cities – preferably American ones, but Dublin would do at a stretch. The real people were mostly, though not always, men, as they seemed to be the ones more likely to take action and live in a willful way. I did not have a concrete sense of how to become a real person, so the only obvious way to begin to approach reality was either to leave my surroundings or to attach myself to a man. I was amazed when I came to read The Fly on the Wheel that so many of my own impulses growing up were echoed in Katherine Cecil Thurston's turn-of-the-century Waterford.

Her 1908 city is in some ways totally alien to my own version, of course. The extreme rigidity of social class is jarring, as is the burden of !nancial alignment in matters of love, and not least the casual normality of a local priest providing family counsel. And yet so much on a deeper libidinous level is familiar enough that the novel’s heart is strikingly modern and fresh. Isabel Costello returns to Waterford and disturbs the solidly middle-class Carey family by her hasty engagement to Frank, a medical student who is supported by his older brother Stephen. Her lack of prospects is disturbing to the pragmatic Stephen, and he endeavours to break the relationship up. But this meddling is only the beginning of a far more troubling turn of events. Stephen is a serious, strong and forceful man – Thurston writes of him: "Yet, despite the lack of physical attractions, the man was a personality. [...] He was one of those beings to whom it is given to claim consideration by a frown – service by a single word."

He is also married to Daisy, and his conception of wives as a class of people is entirely functional. They are of use but of little interest. Daisy is seen !rst as a placid and passive woman almost without characteristics. Stephen's priority in life is not love or pleasure, but rather to remain buoyant and progressive within his social class, inclusion in which he secured with much effort and time. Everything is changed then when he falls instantly in love with the beguiling Isabel, a woman of unusual beauty but also of a natural, raw and unfiltered sort of charm – a way of being that is foreign to his strictly formatted life. The notion of escape, of at last evading the prescribed and dutiful life he inherited, is powerfully seductive and unthinkably dangerous. The growing urgency between the two is played out mostly in a state of suppression, against a backdrop of social engagements and niceties, until the book’s thrilling, devastating culmination.

In Katherine Cecil Thurston’s final novel, Max, the heroine successfully passes herself o" as a man; a related struggle toward self-definition and personal freedom is seen in The Fly on the Wheel in a more typical form. Isabel plainly wishes for Stephen to "draw her with him into the real world". It is this unresolvable and yet totally natural desire which gives the novel much of its hypnotic compulsion, for it is a desire which has endured through the many social changes that Ireland, and the world at large, has seen over the past century.

Katherine Cecil Thurston developed her fruitful relationship to Waterford after the income from her first novels allowed her to buy a secondary residence nearby – a house known as Maycroft – in Ardmore. As Caroline Copeland writes in her thesis on Thurston’s work and life:

It was here that she found the time to work without distraction, and was able to draw on the mood of the countryside and its people for inspiration. Thurston's secretary gives an indication of this in a letter to William Blackwood [her publisher] on 1 July 1907: "Mrs Thurston directs me to write and say that she is waiting until she gets to Ireland to complete the last two chapters of The Fly on the Wheel. She thinks that she could best complete the story in the atmosphere in which the scene is laid." *

It seems not incidental that this home – which she was able to acquire with the increasing wages from her own singular talents, rather than marriage or happenstance – would become the ideal setting from which to explore with such intensity the value of women’s freedom and self-definition.

The Waterford of today is almost unimaginably altered in terms of personal freedom – not only are women free to choose partners for reasons outside of financial circumstances, we are also empowered to demand structural changes which we require for further independence. Some of my most vivid memories of Waterford include my mother protesting for divorce to be legalised in 1995 – a social change which would have deprived The Fly on the Wheel of much of its dramatic force and emotional stakes – and campaigning for the right to choose abortion in 2018.

Despite these advances, the gendered inclination to gather identity and definition by attachment to a man remains an undeniable reality, so much so that to have a boyfriend or husband is fetishised and enshrined and ritually celebrated with the fervour of religion. Indeed, I unconsciously became a faithful believer in it during my young life in Waterford during the early 2000s and would go on to dedicate my first novel to the subject.

When I came to write about this desire, I was careful not to imply that men emerge from this dynamic as the unscathed victors. While men have the substantial advantage of being rewarded for a wilful temperament rather than punished for it, they are also bound by convention and expectation. This is true of Stephen, whose life has been shadowed entirely by the duty to lead his family and behave as the upstanding gentleman his father failed to be. He has agency in the professional and public sphere, but in the most vital sense he has no freedom. For many men, the idea of being led by emotion or indulging in sentiment and vulnerability is, and was, simply impossible.

When Stephen sees the possibility of a new kind of life with Isabel, he rushes toward it in relief and ecstasy – and yet almost immediately he is dragged back down to earth both by his own conscience and by the advice of the wise priest Father James. The priest's admonishment is gently spoken but absolute – he may not break promises to God and to his wife, no matter how dreadful the consequence of this repression. As a reader, witnessing his self-denial is painful – but we know, too, that there is no potential satisfactory outcome. Their world is not the kind that we know now, where internal pain is the only cost of how those in love treat one another. For Stephen to abandon Daisy would be to commit very real harm to her – and their children.

The conclusion to The Fly on the Wheel is bracing, shockingly daring, and casts all that came before it in a different light. There is a kind of vindication in Isabel's act of vengeful madness. She is cleansed by the freedom of total abandon. She knows by then that the desire for freedom in life, the need to be made real in the world, can never be fulfilled in the situation to which she was born. Part of the book's moving power is the nearness of this justified desperation – that it is not so long ago that these impulses which have persisted through the years had a very different outcome. For women, the frustration and rejection and the urge to burn everything down may remain, but now there is the choice to build something different from the ruins and ashes, to choose a different sort of life instead of death.

The Fly On The Wheel is published by Manderley Press. This new edition will be launched at the Waterford Art Gallery on 29th October as part of the Imagine Arts Festival and Waterford Writers Weekend, with Megan Nolan, Fatti Burke and Manderley Press publisher Rebeka Russell in conversation - find out more here.