Caroline Campbell is the Director of the National Gallery of Ireland. She is the also the author of a new book, her first, The Power of Art: a World History in Fifteen Cities.

From ancient Babylon and Jerusalem to modern-day Brasilia and Pyongyang, this is the story of art across 4,000 years. Read an extract below, and Caroline talks to RTÉ Arena above.

In March 1518 the Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarotti came to Pietrasanta in Tuscany, between the mountains and the sea. He had come to source marble from the quarries here for a major commission, the façade of the Florentine church of San Lorenzo. The patron of the project was no less a figure than Pope Leo X, born Giovanni de' Medici, and this was his family’s parish church.

But Pietrasanta was not where Michelangelo wanted to be. He thought the best marble for his task was a short distance up the coast. The Pope disagreed, and in spite of several stormy arguments, Michelangelo was forced to follow his patron's instructions. It was one of many such quarrels in the artist's long career and in retrospect he might have spared himself the rage. That's because the project never came to fruition; five hundred years on, San Lorenzo is still missing its façade.

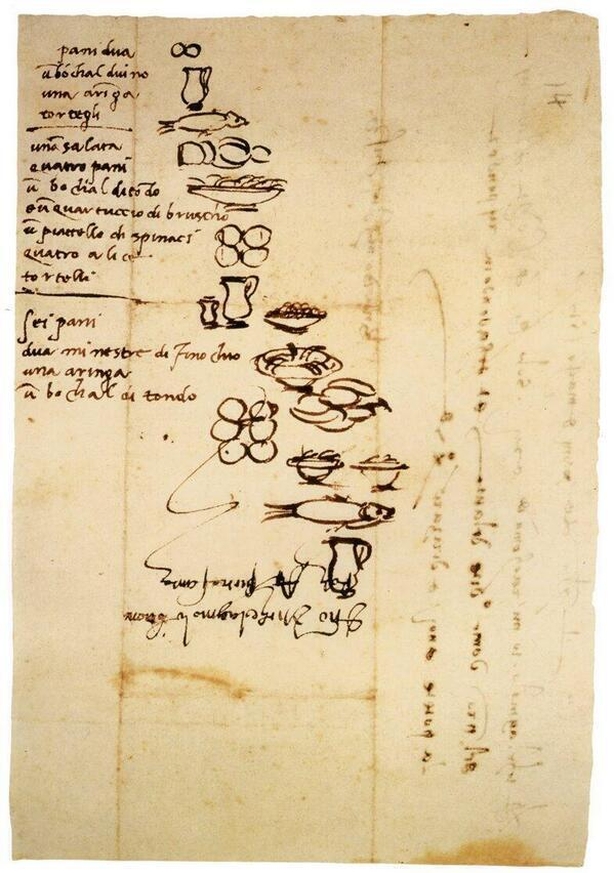

Michaelangelo's sojourn in Pietrasanta did encourage him to produce another work of art, not that he would necessarily have regarded it as such. Jotted on the back of a letter is a shopping list, accompanied by a series of sketches. Presumably Michelangelo’s servant was not able to read so the drawings made clear what he had to buy. What is preserved is the artist's vision of a simple series of meals. He wanted to eat tortelli (a stuffed pasta), anchovies (then just in season), and herring, accompanied by a salad, fennel soup and bread rolls, washed down with jugs of wine. Michelangelo was, unsurprisingly, concerned how the food was to be served. The salad is in a wide, shallow bowl with a slim base, the anchovies’ tails are draped over the edge of the serving vessel, and the herring is elegantly plated on a large dish.

This story is revealing. Even geniuses have to eat. For all his success, Michelangelo had to occupy himself with banal and tedious detail. The artist who enables us to soar and fall with his imagination, from the creation of mankind on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, to the imprisoned souls of his marble slaves, spent a lot of his life arguing over money, how he would support his family, complaining about colleagues, and fighting with his employers. And dealing with his shopping. Artists and creators aren’t a caste apart. Like all of us, they have to live with circumstances and events that are out of their control.

Yet to read most histories of art, the reader might be forgiven for supposing that great artists merely followed their own single-minded trajectory. Also, that their careers follow in neat relationship to each other as part of an overarching, progressive narrative defined by periods—such as Medieval and Baroque—and filled with 'isms' – Mannerism, Impressionism, Cubism, Modernism, Post-Modernism. Of course, these terms can be useful, but they bring major problems. One of the most persistent is the idea that you need to know these concepts to understand art. You only need your eyes or your mind to start thinking about a work of art. Art has existed for as long as there’ve been humans. It’s part of the fabric of our lives, and we are all - although many of us don’t know it - highly trained in looking at it, and analysing its meanings.

what unapologetically I call great art'. (Pic: Anthony Woods)

In this book I’ve wanted to write a history that has the material world at its heart and which pulls on our emotions. Art gains its power from its ability to appeal to our inner beings. It can give solace and connection, but just as emotively, it can foment difference and dissent. Growing up in Northern Ireland during the Troubles has particularly sensitised me to this issue. Art is dangerous, and it can influence us in eloquent and sometimes uncontrollable ways. But it is also uniquely able to connect us to the peoples and worlds of the past. Handling a ceramic bowl, looking at a painting, or standing in a building makes us uniquely aware of those who have done the same before us.

Although art has been made everywhere, it’s been particularly associated with cities. Life in cities is not always civilised, but since the 8th millennia BCE they’ve been beacons for creativity and artistic dynamism. Cities bring people together from many places and backgrounds; they engender a spirit of competition; and the surplus resources that they depend on give people the opportunity to make and patronise art. Nowhere do we find more stimulation or interaction.

So this book brings together the stories of fifteen cities, from Babylon to Pyongyang, at moments in their history that coincided with intense creative activity, with fifteen of the qualities that make us human. My motivation has been to write a history of art that explains the varied contexts within which artists have worked, and which tells the story of people as well as art. I’ve deliberately set out to look beyond Europe and North America. For much of human history they were relative backwaters. Yet this wider artistic world is still barely known to audiences in the West.

(Image © National Gallery of Ireland)

Writing this book, I have become much more appreciative of the things that are near at hand, such as the cup I use every day, and what they tell us about ourselves and about others. But there is something very special about what unapologetically I call great art. Having something beautiful in your life is transformative. Using it or seeing it is a continual pleasure. You don’t need to own it, you just have to be able to consider it as yours. This could be a building you pass every day, a painting in a public gallery (like our Vermeer), a bowl you cherish, or a film you enjoy. Next time you do so, share the experience with someone else. Find out what excites them, and what makes them happy.

In our lives, whatever we do, and however we think, we can all contribute to the story of art even if only by loving it.

This is an abridged and edited version of the Introduction and Conclusion of The Power of Art, by Caroline Campbell, published by Bridge Street Press.