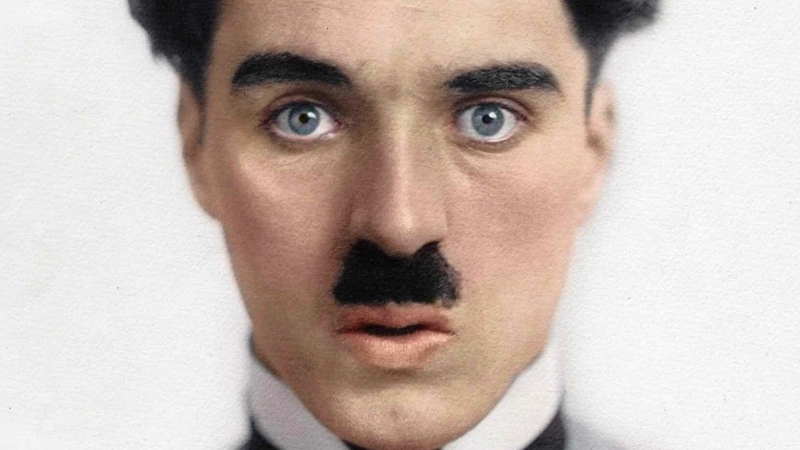

There was a time in history where we had a true universal language. Everyone could understand it. And I mean everyone. It was called Charlie Chaplin movies. Even in our internet age, it's difficult to comprehend how famous this man was. Charlie Chaplin in his time was every Instagram and Tik-Tok star rolled into one - to the power of ten. And he achieved this through the power of cinema. His creation, the 'little tramp', was the everyman who spoke every language, despite (mostly) never uttering a single word.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

To sum up Chaplin’s career in a handful of paragraphs would be the definitive fool’s errand. Famed British director Richard (Gandhi) Attenborough tried to summarise Chaplin in a very entertaining bio-pic back in 1992. A wonderful performance by Robert Downey Jr. as the eponymous star could not compensate for the reems of drama and events left out of Chaplin’s epic life for the sake of its three-hour running time. A new detailed and nuanced documentary on release this month in cinemas, The Real Charlie Chaplin, sets out on the herculean task of encapsulating the flawed, brilliant man who was the people’s 'little tramp’.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

As far as brilliance goes, let me just concentrate on the one thing that absolutely blew me away: his working methods. I grew up a Laurel & Hardy man. When it came to Charlie, even at five years old, my latent cinephile DNA seemingly asserted itself: ‘Silent’ movies with banging piano tracks shown at the wrong speed? Too cheesy. It wasn’t until many decades later, on seeing the great early cinema documentarian, Kevin Brownlow’s Unknown Chaplin, did I have my epiphany. Even a century ago, every director under the sun yelled ‘Cut!’, until they got each set up and shot correct. Not Charlie. He just left the camera running.

Of course, we’re not talking digital hard drives and bottomless terabytes. This was expensive celluloid film stock. No matter. He spent the money because he needed to and he could afford to. Watching these hours of archival footage of Charlie breaking scenes, getting frustrated when ideas fail, getting elated when inspiration comes, all silent of course, are a magical time-travelling experience. The other stunning tool at his fingertips was the power to simply stop. And I don’t mean finishing early for the day when his head just wasn’t in it - I mean for months on end, while still paying the entire cast and crew, until he figured out a scene.

He had the time and we have all this footage because when you are the emperor of all perfectionists it helps you are also one of the highest paid individuals in the world, never mind Hollywood. His initial contract with Mutual Films in 1915 amounted to $670,000 - almost $20 million in today's money - per year! As you can imagine, that amount of money in the early twentieth century gave you an awful lot of power.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

After decades of fame, Chaplin was essentially cancelled (at least in the US) in 1952, following accusations of being a communist. His US residency permit was revoked while heading to London on board the Queen Elizabeth for the premiere of his latest film, Limelight. This ‘cancellation’ was the accumulation of years of bad publicity, smear campaigns and public humiliation (he was particularly hated by FBI head, J. Edgar Hoover). All of this played out in full glare of the cameras across several trials relating to his marriages and relationships with under-age girls. By today’s standards, his career would be dead and buried. Instead, his wife, Oona, returned to the US and wrapped up his affairs. He sold his famous studio lot (today suitably occupied by the Jim Henson company) and the couple made a new home in the tax haven of Switzerland.

When it comes to their crimes and misdemeanours, real or imagined, we usually struggle to separate the art form the artist. Though the world hasn’t had a problem doing just that in relation to Charlie Chaplin’s history. Even America made peace with him twenty years after his exile, when in 1972, he returned to Hollywood to accept an honorary Oscar for his life’s work. Though only making two more feature films throughout his decades in Europe, A King in New York and A Countess in Hong Kong - neither of which were particularly well received - he never stopped being creative. Ill health only prevented him making a film with his daughter, Victoria, called The Freak, in which she would’ve played a winged girl.

His death from a stroke on Christmas day in 1977 didn’t stop Charlie Chaplin from being an entertainer. A year later, his body was dug up and held for ransom. The plot failed, the criminals were ultimately arrested and his coffin found buried in some random farmer’s field. Morbidity be damned, what a suitably fabled farewell for Hollywood's greatest entertainer and the world’s immortal ‘little tramp’.

Charlie Chaplin: A Tear and a Smile, a season of Chaplin classics, commences at the IFI Dublin this weekend.