When you're nine years old, 4:30am is a dark, ungodly hour - at least outside of Christmas.

But it was May. I’d hardly slept with the excitement of not having to go to school for the next three days when I was gently shook awake by my da. Tea and toast down the hatch (our mega breakfast would come later), we hit the road to Liberty Hall in the centre of Dublin.

Three buses waited, packed with my fellow 'villagers’, a motley crew of bleary-eyed folk of all ages, shapes and sizes. Our destination? Childer’s Wood, Co. Wicklow. We were massed undercover of darkness united in common cause: to bear witness to the rising of a king.

I was only in my ninth year, but in some ways I considered myself a ‘veteran’, having already worked on and off as a child actor since the mid seventies. Though up to this day, the start of summer 1980, my jobs had mostly been TV commercials and print ads. I processed these experiences with a certain amount of curiosity and boredom. Unusual though they were, the imagination of a young boy was hardly stirred by downing noodles and drinking milk on cue, or play acting with girls under hot lights while bearded strangers cursed and shouted at you to have more fun. This was my experience of show business.

Even by that age I devoured TV and films. Doctor Who and Star Wars, of course. The Towering Inferno was a big film in our house as my dad, my paternal family in fact, had a long history in firefighting. Still, I felt no real connection between my own acting experiences and the world of movies I loved.

John Boorman would change all that.

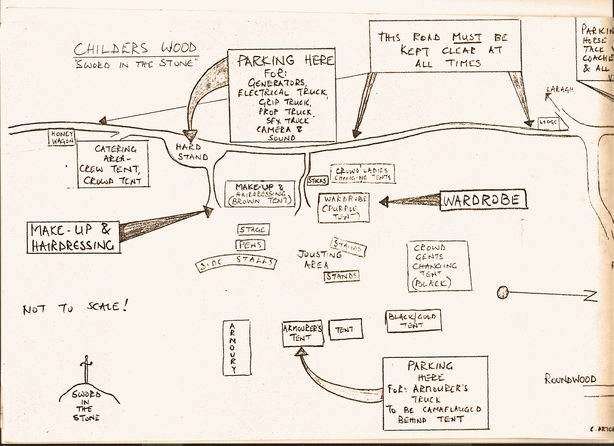

Our buses emptied out at a carpark in Roundwood. From there, we marched en masse to a location somewhere in the forest. All anybody could think about was getting a proper breakfast by then, but the experienced extras knew that wouldn’t come until the final stage in a production line of preparations that wouldn’t commence until we arrived on site.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

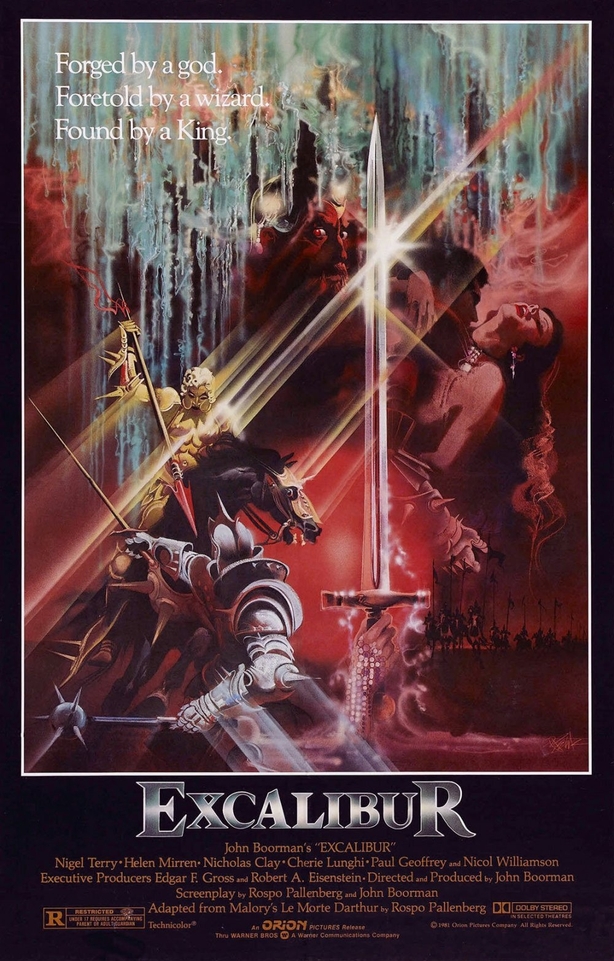

When I went for a costume fitting a couple of weeks before, I was told that the film was called Knights (later it would be changed to Merlin, then finally Excalibur for its release) and had something to do with King Arthur. Still, nothing prepared me for the sight I beheld after emerging from the trees: we all had somehow marched back in time. A whole, fully functional, fully stocked medieval village appeared like Brigadoon in Childer’s Wood. waiting for us to populate it. I was gobsmacked.

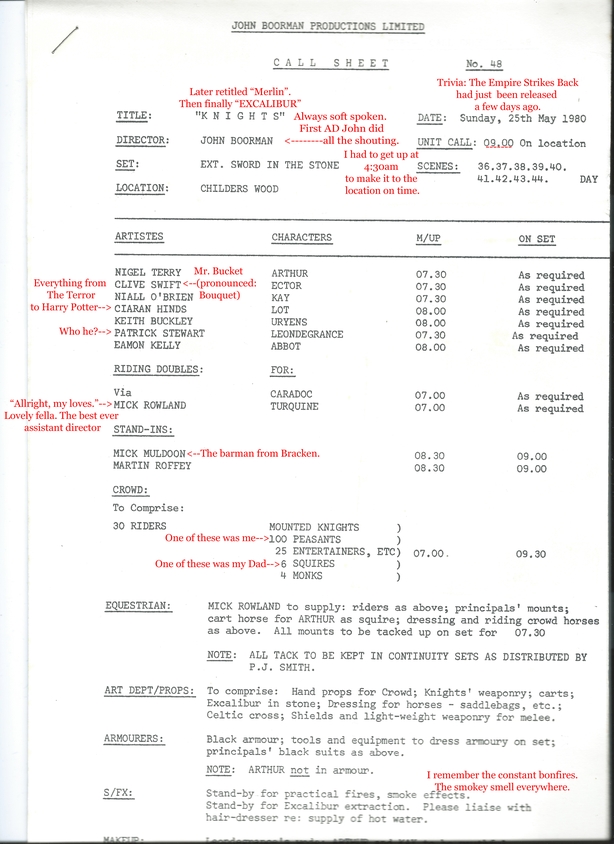

The village, built in a valley, was already teeming with animals, horses and crew (all wearing distinguishing red armbands). Now us huddled masses were to fill it up and inject real life into the place. As my childhood memory has it, there were hundreds of us. Hundreds! Multiple generations of dark-aged folk ready to live it up and get down in the mud for the sake of cinema. But, upon reading the call-sheet today (the daily document laying out the day’s film work - who is to be what, where and when) the crowd line-up says: 30 Riders (mounted knights), 100 peasants (me amongst them), 25 entertainers, 6 squires (my dad being number one) and 4 monks.

Bonfires were burning everywhere, giving the place a constant smoky haze. Most of the sets were shacks or tents. Some of the tents were huge and doubled as stations for costumes and make-up. It was here we queued, first to collect and put on our costumes, then to make-up to be covered in shite - as the jovial fella behind us in the line expertly put it. My costume was a surprisingly comfortable bog-standard set of rags. Plus a wine-coloured beret, which when I look at today seems suspiciously anachronistic.

Medieval fashion plate that I was, I now ‘demanded’ to be fed. I wasn’t alone. Costumed and made up like literal dog’s dinners, the entire peasantry broke for the food tent. Forty years ago, film production was still of the philosophy that you can do anything with an extra as long as you feed them well. Today, you’d be lucky to get a sandwich, an apple and a bottle of OJ to do you for the day. But out in Childer’s Wood we had rashers, sausages, eggs, pudding, bread rolls and as much tea as you could drink (which was a lot, this being an Anglo-Irish production). That was just breakfast! And we hadn’t shot a foot of film yet.

Clothed and fed, our village pacified, we awaited orders from our assistant directors, who directed us to various parts of the hamlet and gave basic instructions to essentially ‘live the moment’. With life expectancy in the low twenties and plague always just around the corner, it was essentially carpe diem one and all. The first part of the day I spent alternating between faffing with farm animals and watching medieval players perform on a little stage - until I was headbutted in the arse by a goat and the unit nurse was called in. (No bruises. Did get crap in my eye.) I’d never been around such creatures before, and I wound this particular goat up so much he stalked me until he got to make his point.

The main shoot was so far away from me I couldn't even see where the camera was. I just kept hearing the crackle of the ADs walkie-talkies, endless disembodied cries of, "Stand by... and turnover… ACTION!" again and again. With nobody allowed to wear a watch - even us extras at the far back - as the day progressed, the peasantry was on tender-hooks waiting for the signal we thought must be coming any minute now: "That’s lunch, everybody!" The AD might as well have cried, "There’s Vikings everybody!" as the village bolted and fled up the hill towards the catering tents as if their life depended on it, not their stomachs. Chicken, beef or fish - I probably had chicken. I can’t remember. But I do remember dessert: chocolate eclairs! Seconds, if you wanted. Plus tea. An endless ocean of tea.

We all rolled slowly back down the hill to return to village life. The afternoon's shooting was to be one of the main sequences in the first act of the film, where during a jousting tournament, squire Arthur (Nigel Terry) goes in search of his brother’s lost sword and accidentally pulls Excalibur from the stone, thus making him king. A fellow raggedy boy cries out, "The sword is drawn!" (I auditioned for this bit out in the woods, but didn’t get it as I couldn’t shout for peanuts) and everybody and their mother bails it up the other hill where the sword Excalibur has been embedded in the stone for decades.

No more goat faffing. I was in the middle of the action now.

With villagers, including my dad and me, positioned closely around the regal rock, I get my first glimpse of The King. My memory of director John Boorman is one of a gangly man waving his arms about, dishing out enthusiastic instructions. While not exactly Mr Shouty, it was clear he knew exactly what he wanted and wouldn’t stop till he got it.

As far as volume goes, nobody could touch the first knight to have a go at drawing out Excalibur - Arthur’s da (Clive Swift) made him stick the sword back in, thinking there’s no way his youngest son of few words was king of all the Britons. This particular knight ate the scenery and would’ve easily swallowed the sword - if he could get it out. His name was Patrick Stewart. Later of the USS Enterprise. He did get his sword in the end, being made an actual knight (arise, Sir Patrick) thirty years later.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Now, time for my close up. I’m not being facetious: there we are, me and my Squire da, front and centre, standing expectantly between Arthur and his da. (I’m biting my lower lip, something I still do all the time.)

Darkness closed in, and as bonfires began to dominate the horizon, shooting was wrapped for the day. After changing back to twentieth century civies, there was only one thing left to do. The reason we were all here, of course: get paid. The village lined up for the last time, now waving our payment chits, and each received a cheque for IR£33 (€140 approx in today's money).

My whole relationship with cinema changed after that. Not because of the money (I got to personally open a Post Office savings account and bought a die-cast Buck Rogers spaceship in Cleary’s with the rest.) But rather than the experience being a kind of spoiler, a reveal of the true nature of making films: its general mundane repetitiveness; the opposite was true for me.

I was now forever bewitched.

My ma tucked me into bed that night and I fell asleep with bonfires in my nostrils, "ACTION!" in my ears, to dream of shouty knights, cheeky goats and one king to rule them all. What a day, I thought, as my eyes grew heavy. And I get to do it all over again tomorrow!

Thank you, da, for introducing me to the magic of the movies. And thank you Mr. Boorman, for letting me live, however briefly, inside your imagination.