We're delighted to present an extract from TCD in the 2000s, the fifth and final volume in the Trinity Tales series - read Two Little Boys by Wayne Jordan below.

Trinity Tales: TCD in the 2000s completes a cycle that began with tales from the 1960s. It invites readers to step into the world of Trinity College as it was in the first decade of this century through the reflections of students who attended the university during those years.

This kaleidoscope of recollections captures a student body in transformation and features stories of personal discovery and achievement against the odds. For some it proved a life-changing era when sexual, racial or class barriers were confronted.

NB: The following story contains language which may cause offense

Two Little Boys by Wayne Jordan

We met doing a play in Players.

He was a crusader and I was a spear carrier. The play was complicated and full of passion and cruelty. We did English accents. A tall girl who wore skirts over her jeans directed. Audiences suffered it. Some friends of mine from school came and were polite. We were children playing at being soldiers. I had a key moment where I screamed about the brutalities we had inflicted and endured in the Holy Land. I assumed regular people just didn't 'get’ the script. Not how I did. Not how we did. The conversations we all had about it. We were clearly plugged into greatness.

On the second to last night, I tied up his shoes for him before he went on stage. The laces wrapped around his calves after a medieval fashion. He sat on a bench and I knelt at his feet.

On the closing night, we had dinner in a pizza place on George’s Street, the whole cast, after the show. I arrived a little late and he had kept a place for me beside him.

He was older than me. Three years. It would mean nothing now, but back then it gave his approval a monumental quality. And he was middle-class, or something like that. He was from the south side, his parents had been to university, they’d lived in Europe, spent the summers outside Dublin, down south on the sea. I adored him. The books he’d read.

I made some joke using a spoon as a prop and he got involved, joining in the performance, the two of us digging away at the restaurant wall with teaspoons. Everyone was laughing. It was a golden moment.

I felt his leg against mine under the table and I was aware that I was made up of a million, million molecules, because every one of them was fizzing and the space between them was honey.

At a house party that night, or a few nights later, we were sat on a sofa in the back room, he and I and someone else who quickly excused themselves. His arm was resting across the back of the couch and I leaned in and our lips met.

I had kissed some boys before. Someone at school. A boy from Liechtenstein in the basement of Eamonn Doran’s. Some laddish chap who knocked around in the Phil or the Hist who admired my dungarees. A friend of a friend at a twenty-first. A chef from the restaurant I worked in. Nothing that amounted to much.

But there was something legit about this kiss. This wasn’t a rehearsal.

His lips were pillowy and a bit dry and that was lovely. I didn’t smoke then and he did and I was excited by the taste of booze and cigarettes off his mouth, which seemed so grown up and so illicit, like I’d just jumped a couple levels in the game of life.

His chin had a rime of lovely stubble on it.

We made out half the night and into the early morning. The taste of him. The texture of his tongue.

We made a little camp of love in the back room of that party across two chairs. Other people were sleeping on the couches and in other beds, in other parts of the house. I had so much desire for him.

He told me to slow down, that we would have plenty of time.

I played with the hairs on his chest in the morning. A matt of chestnut fur. It arranged itself in delicious swirls. There was something baroque about it, decorative, and the treasure trail from his chest to down below his belt.

His body was more compact than mine, which was longer and leaner, a little softer. His was tighter, stronger, more developed. His ribs were steel, his skin was hot. I studied the geography of his torso intently.

We walked to a bus stop together and parted shyly.

We went for a drink in Doyle’s a few nights later, and he asked to be my boyfriend. We talked about theatre and identity and movies and politics and theory and style. It was dizzying.

I felt like I’d won a prize.

A friend we had in common would sing ‘love is in the air’ whenever he saw us after that.

We were a regular sight on the corridors and balconies of the Beckett Centre – canoodling, leaning, chatting, sighing – rapt.

People were sweet to us. And fond. We had good friends, and everyone was our friend.

It felt like the whole kind world doted on our romance. It was a time of ‘coming out’ and declaring ‘pride’ and helping people along with the idea of two boys or two girls together. We felt like soldiers of love. The new poets of desire. We were a beacon.

I loved holding his hand. He loved that I rubbed my eyes when I was sleepy.

The second or third time we were together was in some other friend’s apartment on a pull-out bed. As we pawed each other’s clothes off, I noticed that we had the same underwear on. They were unusual. Black with a blue strip on the side and white piping. I took that as a sign. When we were getting heavy in the dark, I became suddenly alarmed by the amount of fluid that was being generated so I turned on the lights. My nose was bleeding. He was kind and understanding, and I went to the bathroom to clean myself up. When I came back, he was sitting there with a sympathetic grin on his face, but, as he pulled back the covers to invite me back in, he revealed what he hadn’t noticed but I did immediately. There was blood all over his body and all over his crotch. It looked like a crime scene. He washed off and was a bit distant, but it was only a matter of minutes before we got back on the horse. He was on top of me and kissing when he became still for a moment and the light went on again. He had a single thin line of blood coming from his own nose this time. A sympathetic nosebleed to match his sympathetic underpants. I took that, too, as a sign.

Our sex seems so chaste and naïve in hindsight. We both lived with our parents, and it was hard to get a run at it. Kissing and blowjobs, a bit of frottage and some early experiments towards a more advanced practice of lovemaking. But it made me feel beautiful and invincible. Like I was made of light.

I gave up chapel choir to spend more time with him. He, and not my father, taught me how to shave. We got in trouble in the Front Lounge for heavy petting in the afternoon. We had nowhere else to go, so we found nooks and crannies all over college to cradle in – the dressing rooms in the drama buildings, the disabled toilets in the Art’s Block, unused corridors, the shadowy side of new science buildings, the rose garden, under a bush by the rugby pitch.

I stayed with him in his grandmother’s house on Synge Street when she was away for a week. I learned to drink whiskey and cider, and he would make us pasta and sauce whenever we came in drunk. He read to me from the letters of famous Frenchmen and the novels of James Baldwin. His father dropped something over one afternoon and he made me hide in the bedroom.

I went to the Trinity Ball in a purple suit I borrowed from the costume basement, and I had a cream-coloured, ruffle-bibbed tuxedo shirt I wore with it. I drank some vodka from the bottle before I got the 29A to town. I was still a teenager.

He was waiting for me at the top of Grafton Street. He was in a tux and he looked like Steve McQueen.

At a party on a rooftop after, some posh girl made a remark about my clothes and he came to the rescue, though I wasn’t bothered. But I was glad to have a hero. We went back someplace and made puppy love. Home was each other and all our friends and this great experiment.

We said I love you to each other and after that I couldn’t stop. I terrified him. I terrified myself.

I love you I love you I love you I love you.

I became jealous and suspicious and afraid.

He wanted to take drugs and, at that time, that scared me.

He wanted to go places I wasn’t ready to go.

I wanted to box up the world and us and everything, how we looked at each other, how everyone looked at us, and just pack it away, stop it from moving, from changing, from fading away. I wanted to strangle what we had so that I could keep it. And that’s what I did, though that’s not what happened.

For my birthday, he got me tickets to see Nina Simone in concert and a book called The Bone People. On the inside page, in a childish scrawl, he wrote something like – ‘To Wayne, Happy Birthday, You’re deadly, Love X.’ We ate in an Italian place off Meeting House Square.

He couldn’t come to the concert. I went with a friend. Nina sang Pirate Jenny from The Threepenny Opera and the whole world shook. She had a golden dress and a golden fan.

‘There’s a ship/ The Black Freighter/ With a skull on its masthead/ Will be coming in …’

That night he slept with someone else, or two people. Something modern and painful like that.

He told me about it soon after, and we had to break up.

At first I was understanding and philosophical, but that didn’t last for long.

Then came the wailing and drinking and the fingernails down my face. I cornered any poor sinner who would listen to me. My eyes circled in their sockets. Sometimes I banged my head against walls. I was a scandal.

I roped people into this drama with a certain charm and intensity and an exquisitely arranged language of agony. I treated everyone as an audience.

He was still trying to be my friend, and so I tried to kill him with my hands or a knife at a party. I don’t remember. I was blind drunk and devastated. I know I was pulled off him. That was not a golden moment.

I went to the doctor in Donaghmede. I borrowed money from my father. I told him I was in pain and I couldn’t sleep/breathe/concentrate/eat. He was quiet and compassionate and told me I was heartbroken. He said that in time things would be okay, and he prescribed me some B12 tablets.

I listened to Nina Simone on repeat:

‘I get along without you very well/ … Except when soft rains fall …’ I went to some hatchet-faced college counsellor with thick glasses and a dyedscarlet bob. A silk scarf with a print hanging off her shoulder. She told me I needed to own my pain.

This was both true and not true. I was out of control. But it strikes me, still, as a measly response to the size and provenance of my trauma.

I was suffering a major attack of something like PTSD, ignited by this breakup and his rejection, sure, but caused by years of brutal and violent conditioning at the hands of the quasi-fascist Catholic state apparatus that operated divisive hierarchies of sexual shame, and that despised and stigmatized my nature … This was the kind of thing I would go on to learn to articulate at Trinity.

The range of options that had seemed available to me as a young person (to all of us around) could only be described as meagre. A black and white existence with rare flashes of colour drawn from intoxication or the imagination.

But at the turn of the millennium, I had stood on the precipice of happiness, a full-bodied, full-blooded fire of possibility, and nothing had prepared me for having something to lose. So, for a little while, I went crazy. Which I think is fair enough.

I did well at college. Got a scholarship. Tried a PhD.

Became friends with him, eventually. He had troubles of his own.

I’m glad I knew him in the way I did when we were young. He was my Romeo, my Heathcliff. And not everyone gets one of those.

He set me alight.

My mind and body.

And that was only a beginning

I never read The Bone People.

You’re deadly, Love X.

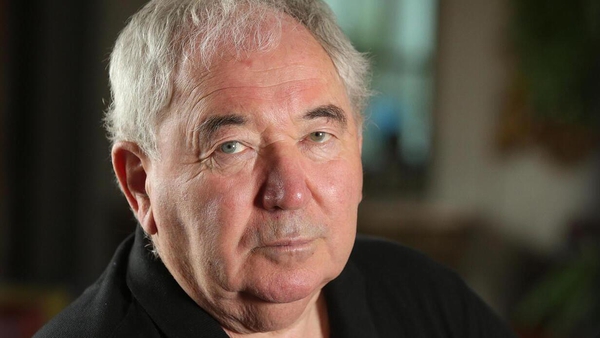

About The Author: Wayne Jordan is a theatre artist and director. During his studies at the Samuel Beckett Centre from 2004–6, he took a year off books to pursue work as a theatre director and never returned. He has worked extensively at the Gate and Abbey Theatres, and his work has toured throughout Ireland and the UK. He lived in Prague for the last three years, studying and making work at a school for experimental theatre and puppetry. Wayne has now returned to Ireland, where he teaches at The Lir National Academy of Dramatic Art at Trinity College Dublin.

Trinity Tales: Trinity College Dublin in the 2000s, edited by Sorcha Pollak and Katie Dickson, is available now from all good bookshops and from Lilliput Press.