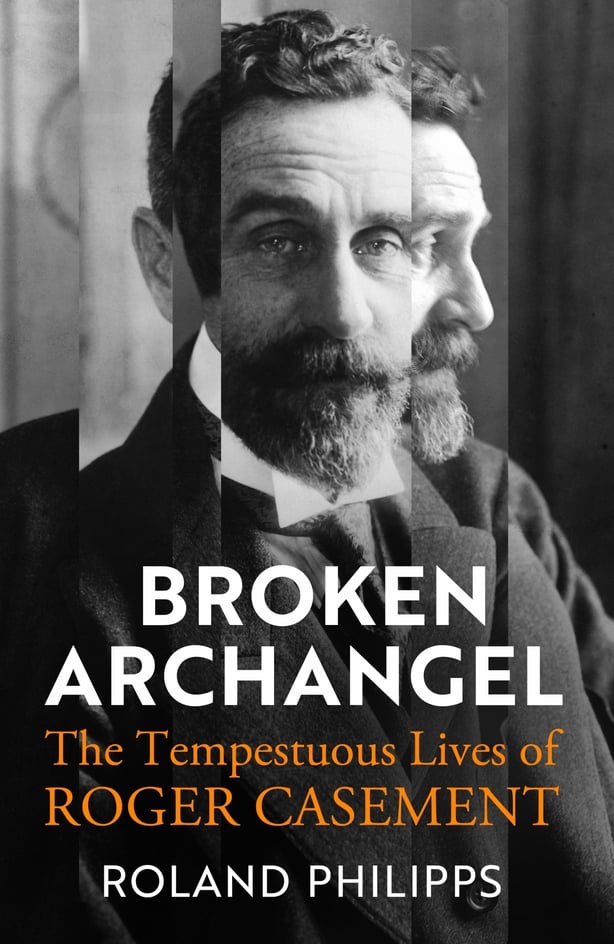

We present an extract from Broken Archangel: The Tempestuous Lives of Roger Casement, the new biography by Roland Philipps.

Pioneering human rights campaigner, patriot, romantic, traitor, LGBTQ+ martyr: this is the story of Irishman Roger Casement, one of the 20th century's most complex and compelling figures.

In 1904, Casement became internationally celebrated for unearthing the grotesque violence of the Belgian Congo. Soon after he won even greater renown and a knighthood for his humanitarian work deep in the Amazon jungle.

But his internal fault lines ran deep: Casement was a contradictory figure made fallible by contemporary mores and his own unexamined emotions. Only decades later did an Irish state funeral finally assert his nobility above his notoriety – and only now can we fully understand his surprisingly modern and deeply relevant life and legacy.

From the Congo horrors on, Casement tended to place a cheerful gloss on unhappiness when he contacted his sister and his niece. Yet his letter to Nina about that morning rings true. As he 'landed in Ireland . . . (about 3 a.m.) swamped and swimming ashore on an unknown strand I was happy for the first time for over a year . . . for one brief spell happy and smiling once more'. As dawn broke over the grassy sand dunes above the beach, ‘all around were primroses and wild violets and the singing of skylarks in the air’. His bucolic spring- time in his own country was to last for only a few hours.

The other reality was that the cold, grey and miserable dawn ren- dered the normally picturesque sweep of Banna Strand, between the gorse-topped arms of the Slieve Mish mountains as far as Mount Brandon and Ireland’s most westerly point to the south, and Kerry Head to the north, forlorn territory for the three men’s perilous and inauspicious homecoming. There was no reception committee. Despite their exhaustion, they needed to move fast to cover the ten miles south-east to Tralee and then on to Dublin. They buried their Mausers, ammunition belts and field glasses in a tin box in case they were intercepted, keeping only their overcoats.

‘The Chief ’, as Monteith called Casement, would not manage the trek, so needed to be hidden until a vehicle could be found. They decided on an old ruin along the coast which they had spotted on the map. Monteith was for taking the straightest line along the beach, but Casement wanted to be out of sight as soon as possible, and insisted they go directly inland before turning towards their goal. After half an hour’s walk, they hit a stinking marshy patch, through which they stumbled up to their knees. Soon the sun broke through and they found a freshwater stream which gave them ‘new life and vigour’. But the ruin was too small and exposed. They continued, passing a farmhouse over whose low drystone wall an untidy, tousle-haired servant girl stared at them ‘in a manner which showed it was unusual for strangers to pass along that road so early in the morning’. Monteith cursed once they had passed her, but was gently upbraided by Casement for doing so. Casement was next to see Mary Gorman in court. They ducked down to hide from a farm cart transporting seaweed, and soon encountered a ring fort about sixty yards in diameter, a shallow, sunken, fern-filled ditch within sheltering wild hedges sur- rounded by fields. They sat to make plans: each man should try to get an inventory of the Aud’s contents to the Volunteers to prepare for the unloading; ‘no consideration of the fate of his companions should turn him from this course’. Monteith and Bailey abandoned their sodden overcoats, first checking the pockets. Monteith found a packet of sandwiches made of war bread and German sausage, soaked with salt water; he started to grind them into the mud but Casement asked if he might try to eat the sludge, though it proved to be a challenge too disgusting even for the famished man.

The Chief refused to hold up his able-bodied companions. Monteith entrusted him with the code sheet, as well as with the photographs of his wife and children which were drying on the grass. He and Bailey arrived in Tralee just before 8 a.m. when many of its few thousand inhabitants were on their way to Good Friday Mass. In their first piece of luck, they came upon a newsagent-cum-hairdresser who could be identified as a patriot by his display of the Volunteer and Honesty, another nationalist paper. He ushered them to a back room for a breakfast of eggs, bread and butter before escorting them to the head of the Kerry Volunteers, Austin Stack. Stack sent for a friend of Monteith’s, Con Collins, to identify him, which took another hour. When the notoriously inefficient Stack was told that the arms ship must be in the bay, he countered that his instructions were that she would not be arriving until the night of Easter Sunday. The cause of the failed rendezvous became clear.

Broken Archangel: The Tempestuous Lives of Roger Casement is published by Bodley Head