When Elvis Costello appeared onstage at Live Aid and introduced The Beatles’ All You Need is Love as "a north of England folk song," I felt a definite shift in my tiny musical mind. The Beatles? A folk song? Why had nobody said this before? Of course it was a folk song – and a great one too – and Costello’s words were just the little nudge that I needed.

Like many people growing up in the north of Ireland, I had already been exposed to all manner of folk music – and not all of it to my taste. I was a very ropey tin whistle player in a school "folk group" that played politely at the Feis, and I was later press-ganged into a so-called "folk group" that played folk-ish hymns at Mass – a genre of music that was to cause my first major rift with religion. Apart from that my only folk credentials were that I knew the words to all The Dubliners' songs – and this was long before I knew the words to All You Need Is Love.

I was well into my teens before folk music, as it might be generally termed at a summer festival, became the sort of (broad) church that actually suited me; where I could find something in all its various sources and tributaries – Paul Brady and Andy Irvine, Planxty and The Bothy Band as well as the various Americans and Canadians who had reinvented the music for the bigger stage of pop, country and rock n’roll.

For me it was all a case of musical travel broadening the mind and, from there on in, I remained determined to keep my mind open. The last thing I needed in my head were the folk police. The old bad cop-bad cop routine.

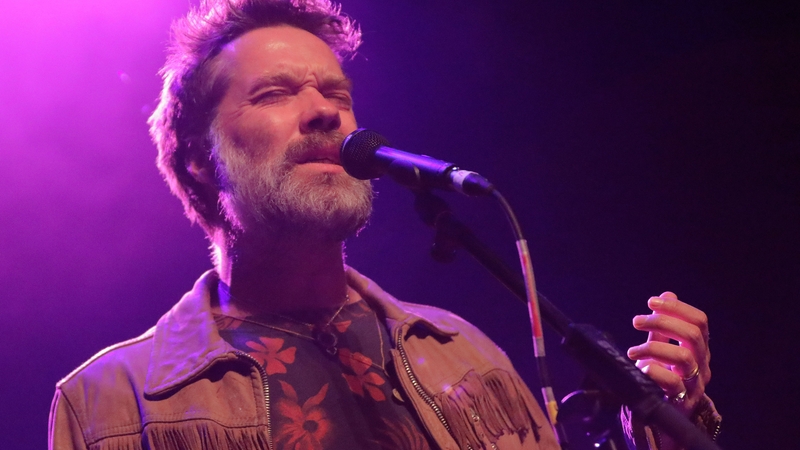

I was thinking about this recently during an interview with Rufus Wainwright who, on his new album Folkocracy, takes a very wide view on what constitutes a folk song, and on how it might be presented. Much attention in Ireland will focus on his brave move to record a version of Arthur McBride – and a very Rufus version too – but the album also includes Shenandoah, Down in the Willow Garden, a song of his own called Going to a Town, Schubert’s Nacht Und Träume, Neil Young’s Harvest and the McPeake’s Wild Mountain Thyme. It’s quite the selection, with quite the guest list of fellow singers including Chaka Khan, John Legend and Anonhi. It’s basically folk meets pop meets classical meet showtunes meets planet Rufus. Sure, maybe it’s not for the purist – but then purists are rarely content with anything.

We need your consent to load this Spotify contentWe use Spotify to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Had any purists been in Vicar Street as Lankum performed their most extraordinary run of shows they would surely have combusted. The band has become a truly magnificent force – not another version of Planxty, not another version of the Bothy Band, not another version of The Gloaming – but their very own thing, and with a whole different set of sonic and cultural influences.

Rooted in the balladry of Dublin City as opposed to the tunes of Clare or West Kerry, some of the songs they chose to play at Vicar Street are the very same songs that over the years, many of us have turned away from, or even completely rejected. The Wild Rover? The Rocky Road to Dublin? – the same songs that I once knew all the words of, long before I was seduced by bands with long hair and bazoukis or Elvis Costello singing a folk song called All You Need is Love. Any yet, in Lankum’s hands, it’s all glorious, powerful, consciousness-shifting stuff – SUNN O))) one minute, Jean Ritchie the next.

I knew Jean Ritchie a little bit thanks to our mutual friends David Hammond and Tommy Makem. I remember asking her how she felt when, during the folk boom of the 1960s, so many artists began to lovingly plunder the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music for the very songs of her mountain childhood – songs she had always been singing, with great dignity, in the background.

"Well," she said, you had a little something in the back of your mind. A little possessiveness. You heard what they were doing to some of the songs that you’d heard sung in their natural state and you’d get a little mad about it. Why are they treating it that way? But still, you have to go along with progress and, in the end, you’re glad they’re using it in some form instead of whatever rock thing is coming along... I remember old Francie Mc Peake said to me, "every twenty years I get out my pipes again." He’s right. It goes in circles. For a while something else gets more popular and the music grows away from the old stuff, but then there’s a generation that comes along and says hey let’s go looking for the roots again."

Mystery Train with John Kelly, RTÉ lyric fm, Mon - Thu @ 7pm - listen back here.