Analysis: We have aspirational, scientific, economic and political reasons to revisit the Moon after decades of space exploration

We are on our way back to the Moon. Two nation groups, one lead by the United States and the other by China, plan to send people to the Moon by 2030, establish lunar bases by 2035 and put boots on Mars by 2040. Their earnestness is seen in the political ratification and budgets now in place; with private enterprise on board through what is termed New Space. Some 400 missions to the Moon are planned by 2032, with the global space economy set to grow from $420 billion at present to $2 trillion annually by 2035. China anticipates its own $10 trillion annual Earth-Moon economy by 2050.

Why are we going back to the Moon?

The age-old desire to return to the Moon and onto Mars has never left us. Successes like the International Space Station and the robotic program for Mars, coupled with technological advances, means that sustained expeditions beyond Earth Orbit are now achievable, with reusable rockets enabling the private sector to get involved profitably. The Moon, then, is the only feasible next destination and we have aspirational, scientific, economic and political reasons to go.

We are an exploratory species, and there is serious science to do: explore our origins and conduct astronomy and applied-science only achievable on the Moon. Water and minerals there are also valuable. Every kilogram of water found on the Moon reduces mission costs there by $1 million. The manufacture of satellite fuel on the Moon will reduce such costs 50-fold; meanwhile lunar minerals can replace diminishing supplies on Earth.

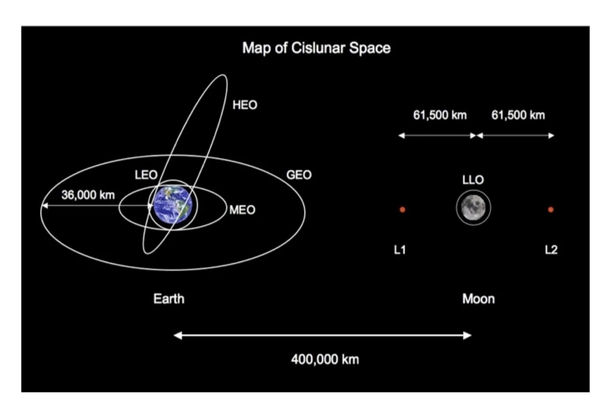

But we're not just returning to the Moon; we are engaging Cislunar Space, the globe encompassing the Earth-Moon orbit, 280,000 times Earth's volume. This is our new domain within which a space economy will emerge for which the Moon will be the hub, laying foundations to move on out to Mars. The scale of Cislunar Space is unprecedented, requiring new space-technologies, protocols and skills to overcome 3-body instabilities, deep space navigation, lunar habitation and mining to mention a few; all toward repeatable journeys into space by broadening sectors of society.

Who's involved with these Moon shots?

The United States with Europe, Canada, Japan and UAE began their Artemis Program with the Artemis-1 unmanned mission to the Moon in 2022. Artemis-II will send four people around the Moon in 2025; with Artemis-III, Artemis-IV, Artemis-V and Artemis-VI to land two people on the Moon every two years from 2028. Accompanying Artemis from 2025 is Lunar Gateway, a space station orbiting the Moon, and a base near the Moon's south pole from 2034.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ News, NASA successfully launches Artemis-1 in 2022

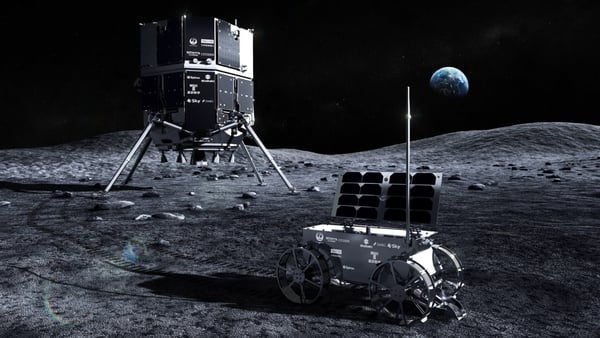

Along with the likes of Boeing and SpaceX, NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Service (CLPS) enables start-up companies to cheaply deliver payloads to, and extract resources from the Moon. The European Space Agency's Terra-Nova 2030+ Roadmap provides habitats, power and propulsion to Artemis and Lunar Gateway; with two European astronauts going to Lunar Gateway around 2030. Irish company Skytec is developing software for Lunar Gateway.

China is leading a parallel program called the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) with eleven countries of the Global South. This phased program is underway with the successful Chang'e orbiter and rover missions including Chang'e 6 which returned samples from the Moon in June 2024. Future plans include the super-heavy-lift Long March 10 rocket to land people on the Moon by 2030 and, in development with Russia, a nuclear-powered lunar base by 2035.

Geo-politics in Space

While not initiated politically, this new endeavour now involves geo-politics. The US-lead program is built on their Artemis Accords, echoing the UN 1967 Outer Space Treaty of space being for the benefit of all. Such a lofty goal notwithstanding, Artemis seems to be privy to countries mainly from the West, embargoing China in particular.

On the other hand, China's CLEP involves countries of the Global South. Per China, it's about "building international partnerships with shared values and a shared understanding of how the lunar economy should work for the benefit of all."

Cislunar Space is also emerging as a new military domain. The new US Space Force, with a budget larger than NASA, is already airing concerns about Chinese and Russian military activity and potential territorial claims in space. China's space program is run by its military, and Russia recently refused to sign a UN treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons in space. Militarisation is now part of the narrative of space endeavour.

Europe's position in all of this is complex. An enduring relationship with Russia in space has been terminated by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Sino-European space activity is equally frustrated for related reasons, with ESA and NASA now working toward a common vision for Space.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ News, China's Chang'e-6 lunar probe has successfully landed on the far side of the Moon to collect samples

Irrespective, Europe, an economic region equal to the US and China, now lags behind both due to lukewarm political ambition and an over-reliance on international partnerships. Europe spends one-tenth on Space compared to the US, and is about one quarter as accomplished as China on a per-euro basis. As a result, Europe will not be meaningfully involved when it comes to decisions on Cislunar Space.

Do we need new space laws and treaties?

As countries establish bases and private enterprise invests, territorial and commercial rights will arise; with new treaties needed. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty and 1984 Moon Agreement are no longer sufficients, Both saw Space as being for the benefit of all, with no appropriation or nuclear weapons and the Moon to be used peacefully, sustainably and free of contamination.

While not everyone is signed up, these treaties are Customary International Law, though remain untested. Indeed the US 2015 Space Act, which gives US space firms right to ownership of resources in space, seems to contradict even the Artemis Accords! There is much to do and treaties are certainly required to avoid conflict.

Society and sustainability

Societal issues arise too. Has sufficient case for such endeavour been made, and does society agree, or have a say? Mindful of how we have transformed Earth over just 500 years, it would be foolhardy not to consider a similar transformation of the Solar System itself in a similar time frame.

Issues of ethos and sustainability will arise. Will environmental sustainability make its way to other worlds, or will we make the mistakes of the past? And if there's life on Mars, how will we treat that life? How we now act will decide what kind of space-dwelling civilisation we become - and what kind of space ecosystem we will leave for our descendants.

Timelines may slip, but our next steps into space are set. Space is becoming a societal endeavour. Geopolitics come and goes, but this is the human story unfolding and each of us is involved, and can have a say. It is worth remembering that for all the technology needed to reach the Lunar south pole, it is water-ice placed there by comets colliding with the Moon millions of years ago - cosmic events out of sight and control - that have shaped our very next steps into space.

What happens next?

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From European Space Agency, Ariane 6's first flight highlights

While it will be several more years before we witness extraordinary missions to the Moon's surface, there are preparatory missions to watch out for. ESA's new rocket, Ariane6, had its maiden launch this month, while SpaceX will conduct the fifth test of their Starship rocket, needed to deliver the Human Landing System to the Moon, later this month. This year will also see several robotic launches to the Moon by NASA's CLSP service: IM-2 by Intuitive Machines, Blue-Ghost by Firefly and the Viper Rover by NASA Ames Research Centre.

Slated for September 2025 is Artemis-2, the first human mission to the Moon since 1972 where four astronauts will circle the Moon on a 10 day voyage. China's Chang'e-7 rover will launch for the Moon in 2026 and test manufacturing on a miniature scale there. Artemis-3 will likely take place in 2028, landing two people on the Moon, with Chinese astronauts scheduled to land on the Moon no later than 2030.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ