Analysis: the story of the origins of hurling is where history bleeds away into myth and legend

By Paul Rouse, UCD

Where do you begin with the history of hurling? Where do you begin with its origins? The truth is that anybody who makes any definitive claims for the origin of hurling doesn’t understand either history or sport or culture, because the story of the origins of hurling is like the story of so many sports. It’s where history bleeds away into myth and legend. And the sources for what happened are just simply not there to tell us when people started playing the game of hurling.

What we are talking about here is a universal human experience. The story of people hitting a ball with a stick is a story which is told everywhere, from Iceland to Ethiopia to the Far East and across to the Aztecs. Look at the lacrosse played by the American Indians, the stick and ball games played by the Mongols, the Berber stick and ball game played on the sands of the desert. The Irish game of hurling is is a modern variant of a theme which is written through history, across millennia.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

The opening sequence to RTÉ One's The Game: The Story Of Hurling

The great mistake you can make in history is to look from the present, into the past and project your experience onto what was happening 200 years ago, 400 years ago and certainly more than a millennia ago. Where we have to go is back into the annals, the old texts, this incredible corpus of material which exists from the medieval period and the stories of stick and ball games being played in Ireland during the time.

READ: How We Made RTÉ's epic GAA series The Game

Was it hurling? Well, it certainly wasn’t hurling as we know it, but there is evidence of people playing with a stick and a ball and we know this from stories of, for example, Cuchulainn and we know it from the Tóraíocht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne. What really matters here though, is that the game that we know as hurling cannot just simply be projected back to the fair green on Armagh where Cuchulainn was hurling against 150 boys or hitting a ball and a stick and catching it before it hit the ground. That is not what was happening.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Eddie Keher shows some young stars of the future the art of lifting the ball from the 1976 series Skills Of Hurling

What happened was when those old texts were being translated in the 19th century, they were being translated in a period of heady Irish nationalism, where the culture of the British empire was sweeping the culture – what was considered to be all Gaelic culture – out to the margins of society. The people who were doing the translations applied the word "hurling", a modern word, to that old story of playing with a stick and a ball.

So, was it hurling as we know it? No it wasn’t - or at least we can’t say that it was. But was it people playing with a stick and ball? It was. You can argue, and I think legitimately argue, that the modern game of hurling is essentially the story of people finding a new way of doing the same thing.

It should also be said that we also have archaeological evidence, a material culture evidence, of what was happening here in the past. For example, there are the hair hurling balls that were found in bogs from north Sligo down into Cork which date back to the 12th century. There was the old hurling stick that was pulled out of a bog near Doon in Offaly from the 16th century. All of these have been carbon dated clearly and are in the beautiful collection in the National Museum. There is physical evidence of this game as it was played.

Of course, the reality of it is we can’t recreate a picture of what that game might have looked like, until we come to the sources, and particular the newspaper sources, and the travel journals of the 18th century. That’s when you begin to get a picture of this game emerging from the murks of time.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, a Sport In Action report on the first Féile na nGael festival of young hurlers held in Thurles in 1971

There is a real difficulty in projecting backwards before then. So what were those people doing who were projecting backwards? Was it something that they were doing by accident or was it by design? I think it’s a mixture of both. I think there were those who were translating words and they found words that came to them and they applied them in ways that were probably inaccurate or they went too far.

And then there were others who saw the potential to create an idea of an ancient Irish civilization, one which predated the conquest and predated the existence of the empire. The British empire may have been the greatest empire the world has known in the late 19th century, but the game of hurling was evidence that the Irish world was something unto itself and something distinct, something different, and I think that really matters.

There is this notion that hurling is a country game, that it’s of the soil. And yes, of course it is, but to imagine that the history of hurling has no urban side to it, is to create a history that is unsustainable and inaccurate.

We can go to Cork and Waterford now, or Kilkenny or Galway, you can go wherever you want – into Belfast – and you can find stories where the game of hurling is as beloved of people who live in urban streets, who live in terraced houses, who live in estates. Their joy, their pleasure, their passion for hurling is every bit as real, every bit as fundamental, every bit as elemental as anybody who comes from the side of a hill or the back of a field. To imagine otherwise is to do a disservice to the game and to the people who love the game.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Tom McSweeney's April 1976 report for Newsround on how a national shortage of ash and a loss of the art of hurley making inspired Portroe GAA club to start making their own hurleys

The idea that the remaking of hurling in the 1880s is a rural thing, something that flowed outwards from Thurles, a kind of a gift bestowed by the people of Tipperary to the rest of humanity, is just wrong. Apart from anything else, the idea for the Gaelic Athletic Association, the initial impetus towards the establishment of that association and the most significant early games were conceived, delivered and developed on the north side of Dublin.

There are GAA people, and there are quite a few of them, who say things and repeat things, and may even believe them to be true, but they’re so hollow. Or at least, there’s hollowness in them, that they do a disservice to truth. And one of those things is this notion of local pride. When GAA people talk about local pride, they do so with a very selective use of facts.

It is a basic fact that from the beginning of the GAA, clubs have been willing to do whatever it takes to win. Winning. The notion that the amateur wants to win less than the professional is of course rubbish. I mean, the wages of amateur sport are medals. And in pursuit of those medals, clubs and counties have gone way beyond their own localities, way beyond their own localities, to find players to improve their team.

People have been willing to bend the rules, always and ever, to win matches. Just like there was a ban on hurlers who were in the British army playing for teams at various stages of history, so there were men within clubs who disregarded that ban, and the hurlers around them disregarded the fact that they had a British Army soldier or a policeman amongst their ranks. All the better to win. Just as people were willing to take in people from other clubs to pad out teams. This happened from the very beginning.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, a RTÉ News report from 2007 on the launch of Gaelic Games Hurling for Sony’s Playstation 2

Yes, there is local pride. Of course, there’s local pride. You’d be a fool to argue that local pride isn’t essential. But it’s not just local pride. It’s about winning and it has always been about winning. That pursuit of success explains why an ad hoc arrangement developed first in response to the wholesale cheating that was going on, where any club who won a championship packed out its team with some of the best players it had played against in the local club championship. And you got the evolution by the bending of the rules, in the great Irish way, to the point where a new rule is made. And that new rule means it’s no longer the club that represents the county, but all the clubs who represent the county.

There are people who would have you believe that it is only a lack of exposure to hurling that prevents the world from taking up the game of hurling. They would have you believe that it is just the mere sight of stick and ball and Gael rampaging around Croke Park will somehow convince others of their sporting failures and, and draw them into our tent, so to speak.

Of course it’s rubbish. Anybody who wants to understand just how great a pile of rubbish that is, should look around Ireland and at the map of Ireland and just make a list of all of those places in this country where there is no hurling. Places where hurling is as foreign a sport as lacrosse is. Places where people just simply don’t engage.

What the GAA has done is create a framework in particular counties, dependent on local tradition and individuals, to drive the development of the game. There are stories from various parts of the country which are not traditionally considered hurling heartlands where the game prospered, because of the actions of a particular guard or a teacher, or a small group of people within a particular area who made a hurling club and made hurling a beloved game in a particular place.

The singular failure of the Gaelic Athletic Association when it comes to hurling is a failure to broaden the base. The reality is you can write down the names of one quarter of the counties of Ireland, and you can make a very sizeable guess that it is from those eight counties that the next 50 All-Ireland hurling championship winners will come from.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, one of the first live sport commentaries anywhere in Europe was radio’s coverage of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Semi-Final in August 1926. Philip Greene gives the background to early sports coverage on Irish radio and Jimmy Mahon, a young technician on those early broadcasts, recalls "Carbery", the first great Irish radio commentator.

You look at the Offaly players who won the All-Irelands in the 1980s and they came from the great schools teams of the 1970s, and from a very solid competitive local club culture. All the teams from the 1990s had underage medals won with Offaly and with their schools.

No county has ever made a breakthrough without having two basic things. Number one, a proper underage and schools development system. Number two, a significant number of clubs playing the game to a reasonable level. Without those two things, it is impossible. If you look at any county that has made the breakthrough in modern times, it is dependent on those things.

You can’t look at any county where this is not the case. It is a fundamental building block for senior success, and yet it is proved entirely elusive across great swathes of the country where hurling is essentially terra incognita.

There is a further factor. Probably the greatest factor impeding the spread and growth of hurling is not rugby or soccer or video games. It’s not anything except Gaelic football. In GAA clubs where Gaelic football is strong, there is an understandable but real reticence to allow hurling be promoted to a level at which excellence can be developed to an extent to make that club or that county truly competitive on a national scale.

There are exceptions – there’s Slaughtneil in Derry - but broadly speaking, hurling is impeded by Gaelic football. What other way does that work? Well of course it works the opposite way because Gaelic football is impeded in clubs where hurling is dominant. It’s logical. Why would you throw down a game at which you’re successful, or relatively successful, a game which you love and chose another? They’re totally different games, they’re within the same organisation, but they’re entirely different games.

This piece is taken from an interview given by Paul Rouse for The Game: The Story of Hurling, a new three-part TV series beginning on RTÉ One on Monday July 30 at 9.35pm

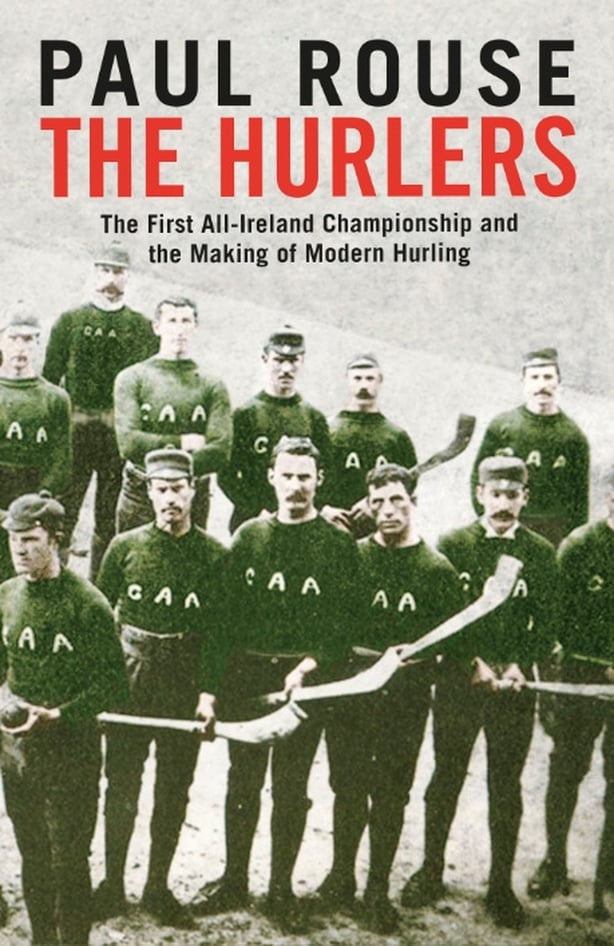

Dr Paul Rouse is a lecturer in the School Of History at UCD. His book The Hurlers: The First All-Ireland Championship and the Making of Modern Hurling is published by Penguin. He is a former Irish Research Council awardee.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ