Analysis: the west Cork marine nature reserve is home to species that would more typically be found in deep sea ecosystems

By James Bell, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Rob McAllen, University College Cork, and Valerio Micaroni, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

Deeper than most scuba divers can safely work and above where most underwater robots are designed to descend lie some of the most poorly studied ecosystems in the world. Between 30 and 150 metres down is the ocean's mesophotic zone, meaning middle-light. Communities of life exist here at the limit of where photosynthesis can occur. On rocky surfaces in the cold water, seaweeds slowly give way to sponges, anemones, and sea squirts – small tube-like creatures that filter plankton from the water.

Sandwiched between shallow and deeper environments, these twilight ecosystems offer food and habitat to the fish and other species we catch. The lower light levels mean they can forage with less risk of being seen and eaten by predators.

But the distance of these ecosystems from the surface doesn't spare them from human influences. Sediment and nutrients from farms and mines obscure the light reaching the seafloor, while fishing pots and nets can damage the fragile animals living in mesophotic ecosystems. Rising sea surface temperatures are likely to be affecting these areas in ways we still don't understand, as their remoteness makes it very difficult to study.

Remarkably, one of our best guides to what's happening down there can be found much closer to the surface, in a saltwater lake tucked away on Ireland's southern coast.

Lough Hyne marine reserve

Lough Hyne is the Republic of Ireland's only marine reserve – a protected area of the ocean – and it supports more than 1,850 species in just half a square kilometre. The lough is more than 50 metres deep, but even in its shallows, animals and plants grow that would more typically be found in the mesophotic.

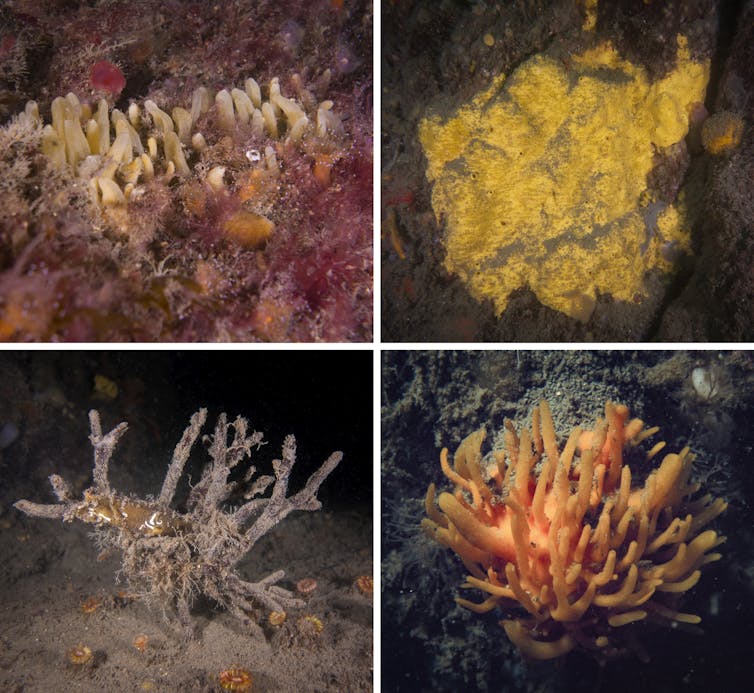

Sponges and anemones that are usually found 30-40 metres down occur in the lough as shallow as five metres. In research we published 20 years ago, we described the wide range of animals living beneath the surface on the rocky cliffs, including cup corals, wandering lobsters and spider crabs. Most conspicuous are the sponges, which form dense gardens of more than 100 species.

The lough is connected to the Atlantic Ocean by a narrow, shallow channel. The rocky sill that runs across it restricts the water flowing in and out, with currents only detectable inside the lough during the incoming tide. This relative calm lets sediment in the water settle and reduces how much light can penetrate. These conditions, combined with the lough's sheltered nature, create ecosystems at shallow depths that would normally emerge in much deeper water. Lough Hyne lets scientists study the mesophotic without the logistical challenges of working there.

A dramatic shift

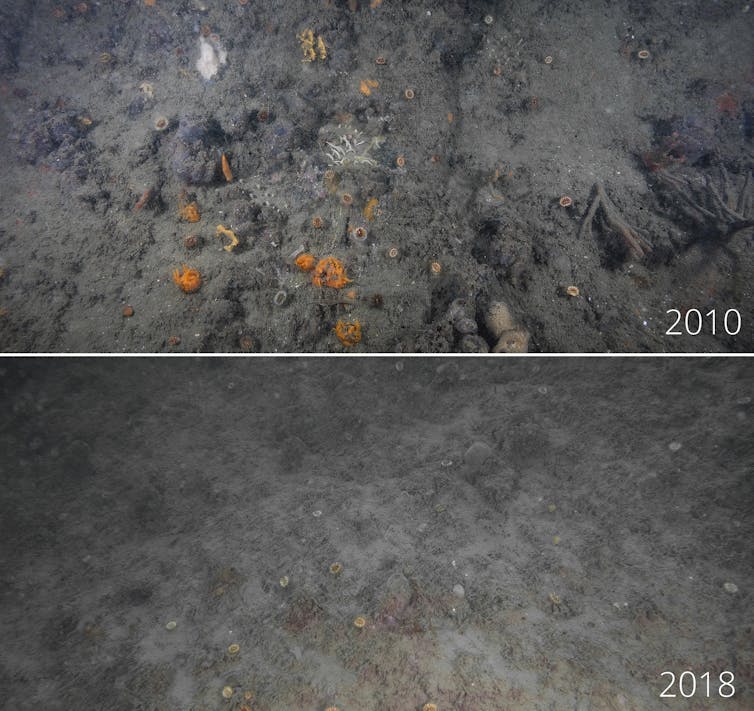

The mesophotic communities of the lough were thought to have changed very little for decades. That was until a 2016 visit, when we noticed a dramatic shift.

In recently published research, we reported how the abundance of sponges in the lough shrank by half between 2000 and 2018. Slow-growing sponges, particularly those species which form branches, were worst affected. In some places, sponges had disappeared completely. In their place, faster-growing sea squirts and dense tufts of seaweed had proliferated.

These changes were most dramatic where water currents were at their weakest, in the lough to the west. Unfortunately, there has been no consistent monitoring of the lough's underwater cliffs, so it's impossible to say exactly when the change occurred. But based on older surveys and conversations with regular visitors, we think it happened sometime between 2010 and 2015.

It's difficult to be certain what caused the change, whether it was a natural event or the result of human activities. There could have been a sudden increase in the amount of sediment reaching the lough from the surrounding land, or an unusual quirk in the lough's chemistry, or a sudden change in temperature.

Sponges living just outside the lough in shallow water don't appear to have been affected. But we have no idea if mesophotic habitats around the coasts of Ireland and Britain, similar in species make-up to those in Lough Hyne, have changed too.

Thanks to support from Ireland's National Parks and Wildlife Service of the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, we've established new long-term monitoring stations – areas of the seabed we've marked out to return to year after year – on the underwater cliffs, to assess any further changes. Happily, we are already starting to see new sponges starting to settle and grow.

At this stage, it's not clear if all the sponge species will return, or how long it might take for the larger sponges to grow back. To our knowledge, the sudden disappearance of sponge gardens on this scale has never happened in the lough before. Our new surveys will help reveal how fast these unique communities recover from disturbances though, and allow us to track any future changes, as well as their causes. Not only will this help us better manage Lough Hyne, but also other mesophotic ecosystems across the world.

James Bell is Professor of Marine Biology at Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington. Rob McAllen is Professor of Marine Conservation at University College Cork. Valerio Micaroni is a PhD Candidate in Coastal and Marine Biology and Ecology at Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington. This piece was originally published by The Conversation.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ