Analysis: The story of the 19th century Tipperary tennis ace and 'dark horse' who won the Wimbledon tournament in 1890

This article is now available above as a Brainstorm podcast. You can subscribe to the Brainstorm podcast through Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

It was a wet afternoon when Irish tennis player Lena Rice stepped on to the Wimbledon courts in 1890 for the Ladies' singles final. Attendance at the match between Rice and British player May Jacks 'rapidly increased’ to around 1,000 onlookers despite the rain and Rice, aged 24, ‘showed her superiority at all points’. The Tipperary woman took home the trophy, winning 6-4,6-1. This remains the first and only time an Irish woman has won the coveted title at Wimbledon and Lena's was a short but memorable career.

Born Helena Bertha Grace Rice on June 21, 1866, near New Inn, Co Tipperary, she was the second of Ann (neé Gorde) and Spring Rice’s eight children, in a prominent, landed family. ‘Lena’ grew up with two sisters and five brothers at Marlhill, a two-storey Georgian mansion where her parents ‘entertained lavishly’. She began playing tennis at home with her sister Annie, who also went on to compete, before joining the local Cahir Lawn Tennis Club.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Sunday Miscellany, Tommy O'Rourke tells the story of Lena Rice, the first and only Irish woman to ever win at Wimbledon

It was a dazzling debut in May 1889 at the Irish Championship at Fitzwilliam Square in Dublin, when Rice first played competitively. She was defeated by leading British player Blanche Bingley-Hillyard in the semi-final, who she also played with in the doubles final and lost. But Rice did win the mixed doubles title with men's sensation Willoughby Hamilton, who came from a prominent Irish sporting family.

The Freeman's Journal had high hopes for the Tipperary talent. Reporting on the Irish Championship that year, it said 'Miss L Rice’ made a ‘most brilliant and at the same time tantalising display'. She should have beaten Mrs Hillyard 'very easily', the reporter wrote, but it was her first appearance in a championship and nerves got the better of her. ‘It is to be hoped that Miss Rice will do herself and her country justice by competing again, and without impertinence, it may be opined that she has a grand future before her in tennis circles.’

Read more: Can Ireland ever produce a Wimbledon champion?

At the time Lena was playing tennis, 'she's at a sweet spot, there’s a tennis boom in Ireland,’ says Dr William Murphy, Lecturer in the School of History and Geography, DCU. Tennis was very much a landed or upper middle class sport in Ireland at this point, says Murphy. Tennis "comes along and becomes the new sporting leisure fad" in the 1870s. On the grounds of Ireland’s ‘Big Houses’ "people had the leisure time and the space to create tennis courts and that was one of the key spaces where tennis is played in the 1880s and the 1890s", with the sport spreading out into clubs founded in the suburbs and provincial towns.

Between 1875 and 1889, the first 15 years of tennis club formation in Ireland, 45 clubs are established. Then between 1890 and 1894 alone another 55 clubs appear, Murphy says. This massive and sudden expansion is documented by historian Tom Hunt in Sport and Society in Victorian Ireland: the case of Westmeath.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, after 120 years Fitzwilliam Lawn Tennis Club votes to admit women to full membership (broadcast December 10, 1996)

The 1890s are the 'boom years' for tennis club formation and the most successful years for Ireland competitively. Rice’s aforementioned doubles partner Hamilton would become the first Irish man to win Wimbledon in 1890 and this would be be the first of seven Wimbledon singles titles for Irish men in the 1890s. Meanwhile, another Irish woman, Kilkenny's Mabel Cahill, won two US Open singles titles and two doubles titles in 1891 and 1892, earning her a posthumous place in the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

Having wowed with her Irish debut, Rice then crossed the Irish Sea alongside her sister Annie in July 1889, to make her debut at Wimbledon. She made it to the final, and came close to winning, but having failed to take several match points in the second set, Rice lost 4–6, 8–6, 6–4 to Hillyard. Though she didn't win the tournament, she became the first woman to officiate at Wimbledon that year. The Pall Mall Gazette said she was "an Irish player who has only recently become famous' who had 'a freedom of stroke and a mastery of the back hand that is rare among lady players.’

Rice’s second season as a competitive tennis player kicked off with a win in the 1890 singles’ tournament at Landsdowne Tennis Club. She then lost the Irish Championship singles, but won the doubles and mixed doubles, before travelling to England once again to grab her second chance at Wimbledon glory.

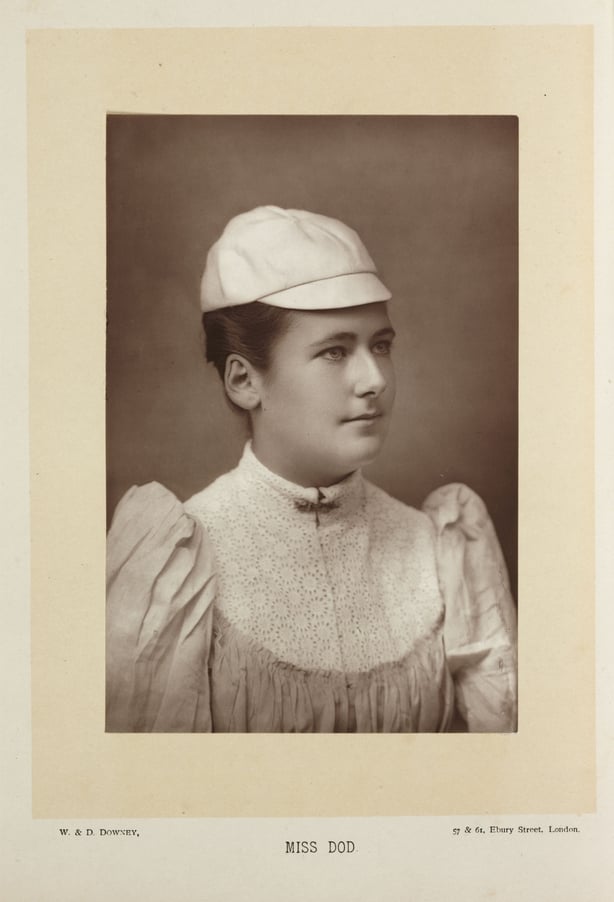

She faced just four entrants in the 1890 Wimbledon Ladies' tournament: neither Hillyard nor Lottie Dodd, considered the best player of the era, entered that year. Having defeated Mary Steedman in the semi-final, she then met Jacks in the pivotal final that would cement her place in Irish sporting history. Accounts of the time show her performance meant she was considered a 'formidable rival’ (Gentlewoman), while sporting magazine Field reported that ‘Miss Rice showed first class form, and seems to improve each time she plays in a tournament’.

But there was no grand future for Rice in tennis as the Freeman's Journal had hoped. Though still young, she disappeared from the tennis circuit almost as quickly as she had appeared: Rice didn't contest her Wimbledon win in 1891 and never competed publicly again. We don’t know much, if anything, about Rice’s life after her whirlwind tennis career or why she stopped competing. One year after her Wimbledon win, her mother died on March 17, 1891 and her death is considered to be at least part of the reason why Rice didn’t continue. Murphy adds there’s no sense that she perceived herself as having a 'tennis career’ and that 'perhaps explains a pretty rapid drifting away’ from the sport.

"It may also be something as simple as, she's sort of achieved the pinnacle in tennis when she wins Wimbledon. "This is still a time when it very much is a leisure world in some ways, as distinct from what will become a highly competitive sport, where people are training regularly and preparing and winning these kinds of things is a measure of some sort of profound sporting ambition."

Historians Simon Eaves and Robert Lake analysed the brief rise to prominence of lawn tennis in Ireland in the late 19th century and pointed to the wider political and social developments as being a factor in tennis' relatively rapid decline in popularity. "One of the reasons tennis reaches a peak and is less influential after the 1890s", says Murphy, "is because you see a decline of the Irish landed classes, with the introduction of the Land Acts in the 1880s and gathering pace in the 1890s. So the social and economic foundation of the sport sort of falls away quite quickly."

While tennis was experiencing a boom in Ireland, so was the cultural revival: the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) was founded in 1884 and the Gaelic League (to become Conradh na Gaeilge) in 1893, while the Irish Literary Revival was also in full bloom.

With some more experience, Rice would have made a 'dangerous rival' to the top women's player of the day, Dodd, Harry S Scrivener, who helped found the British Lawn Tennis Association, wrote in the 1903 book Lawn Tennis at Home and Abroad. Scrivener called her career 'short and brilliant’ and said she was ‘a wonderful player with a terrible "Irish" drive and a powerful service’.

In a testament to the lasting impression Rice made on the sport, when asked to write about her most memorable and noteworthy match for the 1910 book Lawn Tennis for Ladies, Hillyard chose to write about her first encounter with 'dark horse' Rice, the 1889 Wimbledon final, two decades after the pair had met on the court. ‘I started very nervously, as Miss Rice had given me rather a fright in the Irish Championship the month before,’ she wrote. After the newcomer took the first set 6-4 and was winning the second, Hillyard recalled turning to the umpire, Mr Chipp, and saying: ‘"What can I do?" His grim answer was, "Play better, I should think."’

The 1901 census tells us that a decade after disappearing from the sporting world, Rice, then aged 34, was living at Marlhill with her older sister Catherine, 36, who was head of the family. Both were listed as ‘owner of land and dividends’ and as unmarried, with their religion noted as Church of Ireland. The sisters had two servants living with them: Mary and Josephine Hally, aged 19 and 18 respectively, who were unmarried and Roman Catholic. Under Education all four were described as ‘can read and write’.

Rice died on her birthday, June 21st 1907, aged 41, at Marlhill. Civil records show the death was notified to the county two weeks later, on July 5th, by her brother Robert, but it wasn’t officially registered until October 26th. She died from toxaemia associated with a tubercular abscess that had become septic. She was listed as a ‘spinster’ and a landowner. Meanwhile, the probate will shows she left £2,554, 10s and 3d to her sister and executor of the will, Elizabeth, also a ‘spinster’. The Irish Independent reported that she left ‘£25 each to the New Inn Church and Dr Bernardo’s Homes’ as part of her personal estate.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ