Analysis: Heron travelled to post-war Paris on a motorbike, taught herself to weld and broke down barriers

By Billy Shortall, TCD

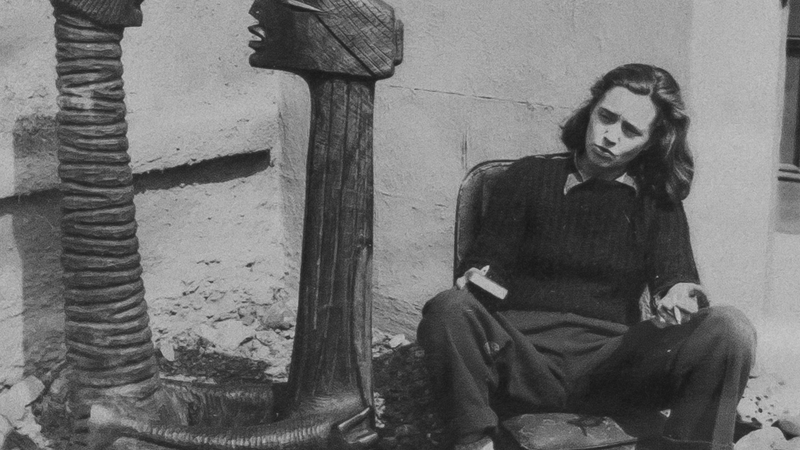

Sculptor Hilary Heron (1923-77) is not a well-known artist, despite being a pioneering modernist in the historiography of Irish sculpture. She was regarded in her lifetime as "Ireland's only modern sculptor", and more recently Heron was noted as the artist "who was to become the pioneering figure in modern sculpture in Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s".

During her lifetime she had solo shows in Dublin and London and represented Ireland at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 1956. She exhibited elsewhere in Europe and the United States as part of group shows. Travel, and in particular her early career trip to Paris, was important to her work. The first survey exhibition of Heron since her death in 1977 will open this week at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) and will travel to the FE McWilliams’ Gallery in Armagh in November.

Born in Dublin in 1923, her parents were from Armagh, and she spent her early years in Coleraine before moving to Wexford, the family travelling with her father's bank work. She retained a northern accent all her life. Heron stated that she never "consciously wanted to do anything else other than sculpture" and moving to Dublin she entered the city’s National College of Art (now NCAD) in 1941. Her success was immediate, winning college awards, and she joined a very select group of artists by winning the important Taylor Art Scholarship Prize, an annual competition established in 1878, in three successive years.

She exhibited at the inaugural Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA) in 1943. The IELA was established by artist Mainie Jellett and others to provide an exhibition space for more avant-garde art, although not excluding academic or traditional work it became the main outlet for modernism in Ireland. The IELA offered a travel scholarship in honour of Jellett, their first president, who died in 1944. Heron won the £250 award and with her prize money she unconventionally bought a motorbike and drove to Paris via England. This was just three years after World War II had ended and its destruction was still in evidence all along her route. Paris in 1948 was the centre of the art world and the year Heron spent in the city was impactful on the work she created throughout her career.

Heron was related to the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, through marriage and she initially stayed with him and his partner Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil before moving to a chambres d'hôtes in the city. Heron socialised with Beckett, and he guided her to exhibitions and introduced her to artists, critics, and galleries. Art changed in the post-war period, particularly in Paris, where there was an outburst of ideas and creative energy, enriched by an interplay between art, literature, cinema, music, philosophy, and photography.

Many artists who had worked in an abstract and surreal style before the war, returned to a period of figuration as a means of reasserting the importance of the human figure after witnessing its destruction in war. Men and women destroyed by war would be put back together in art. Existentialism in Paris defined the epoch after the calamity of the war and the horrors of the Holocaust when a generation had lost their faith in perpetual peace, progress, and hope for the future. The nuclear threat was a reality.

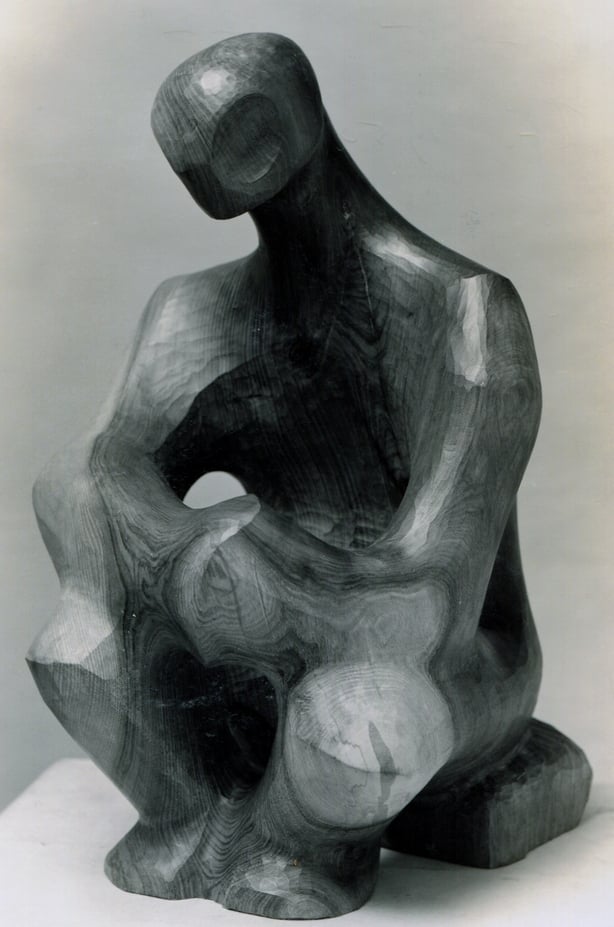

The company of Beckett, the creative Paris environment, and the destruction Heron saw is evident in the work she created on her return to Dublin and exhibited in her first solo show in 1950 at the Waddingtons Galleries. Heron was aware of sculptors Constantin Brancusi and Henry Moore's modernist ideal of 'direct carving' and 'truth to materials’, and it was this approach that was to first mark her sculpture as modern.

She travelled to the Venice Biennale from her Paris base in 1948 to see a Moore show. Works from her first exhibition, such as, Andante (1949) is a brooding and isolated figure; Horse Chestnut (1949), alternatively titled Human Child in Heron's photograph album, displays a vulnerable being in a womb-like shelter; while Flight into Egypt (1950) is an allegory for the existentialist threat to the human race. The works in her exhibition stressed the humanist element and valued the agency of the human being.

In Paris, Heron had seen welded iron used as a sculptural technique for the first time. The characteristic medium of ambitious modern sculpture between 1945 and 1960 was welded iron. Before WWII, Julio Gonzalez and Pablo Picasso had pioneered welded sculpture and after the war it was used by many modernists in Europe and America such as Alexander Calder and David Smith. On her return, Heron bought an oxy-acetylene welder, taught herself how to use it, and became the first artist to exhibit welded sculpture in Ireland at her second Dublin solo show in 1953. Welding became central to Heron's practice in the early 1950s and one of the first times she used it was for a government commission.

The Irish Pavilion at the Frankfurt Trade Fair was regarded by officials as not being distinctively Irish and a meeting at the Cultural Relations Committee (now Culture Ireland) was convened, they wanted to embellish the building with an Irish emblem. It was required to "be modern" as they wished to present a modern image of the young state internationally. Heron’s work fitted the bill and she designed and made a giant elk head out of welded steel and walnut to sit on the roof apex over the entrance to the building in 1952.

Heron's stature as Ireland’s foremost modern sculptor was re-enforced in 1956 when she was selected with Louis le Brocquy (1916-2012) to represent Ireland at the important Venice Biennale. A photograph taken at this exhibition shows Peggy Guggenheim examining a welded-steel piece, Cock-a-doodle-do (1956), with the Irish commissioner for the show, James White. Heron’s carved sculpture, Our Lady of the Rocks (1953), a play on Leonardo’s Madonna of the Rocks (1480s), a painting that she was familiar with from the Louvre Museum, is visible in the background.

Moving to London in the late 1950s, Heron held her first solo show in the city in 1960. Sharing a studio with her friend, English sculptor Elisabeth Frink, she had ready access to bronze casting and exhibited bronzes along with welded and carved works. Again, she acted on a work she saw on her first Paris trip repurposing aspects of Rembrandt's Carcass of beef (1657) along with Francis Bacon’s Slaughterhouse paintings, then on view in London, to create her Torso sculptures.

Among her commissions around this time was for a sculpture to embellish the new Bord Fáilte Offices on Baggot Street. Like tourism and travel in the early 1960s, visual modernism denoted internationalism and Heron's abstract work fitted this brief seamlessly. She created the wall piece Clonfinloch (1961) for the entrance to the new office block. Drawing on the past, she appropriated the Bronze Age markings on the Clonfinlough Stone near Clonmacnoise, Co Offaly and repurposed them in her striking abstract work. Clonfinloch presented the new as a return to pre-colonial Irish art and in doing so harmonised historic Irish art with the international modern.

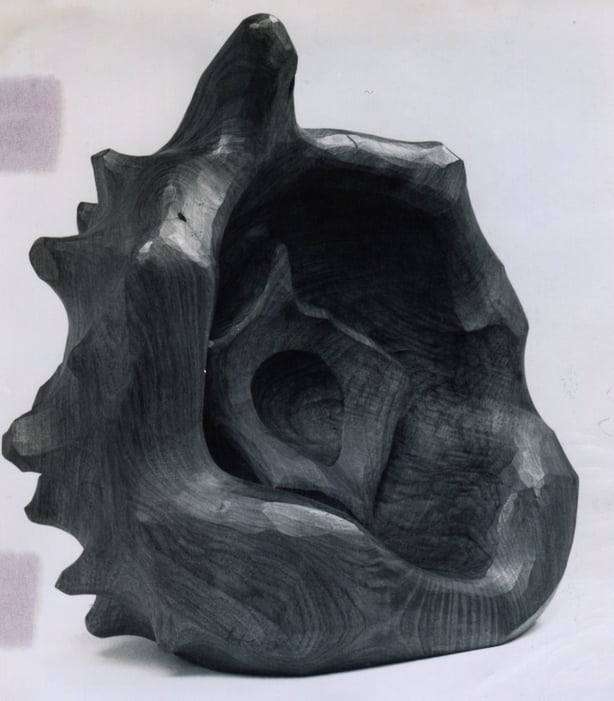

Her last solo show in London in 1964 saw Heron look back again to her time in Paris. Heron presented her interest in nature and the sea is a series of Lithodendron sculptures by repurposing work she had seen in Paris by Alberto Giacometti and kept copies of in her notes, exemplifying the importance Heron’s time in Europe had on her artistic practice, and the role international travel, in general, had on the development of Irish art.

Hilary Heron: A Retrospective is now on show at IMMA.

Dr Billy Shortall is an art historian and leading Hilary Heron scholar in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Trinity College Dublin.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ