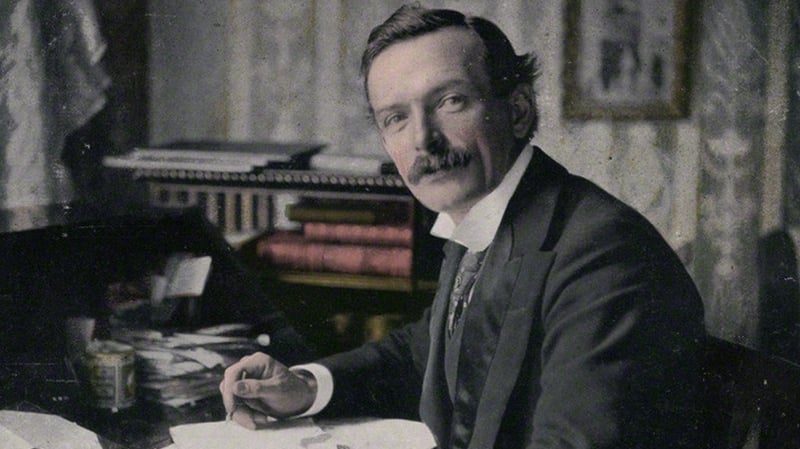

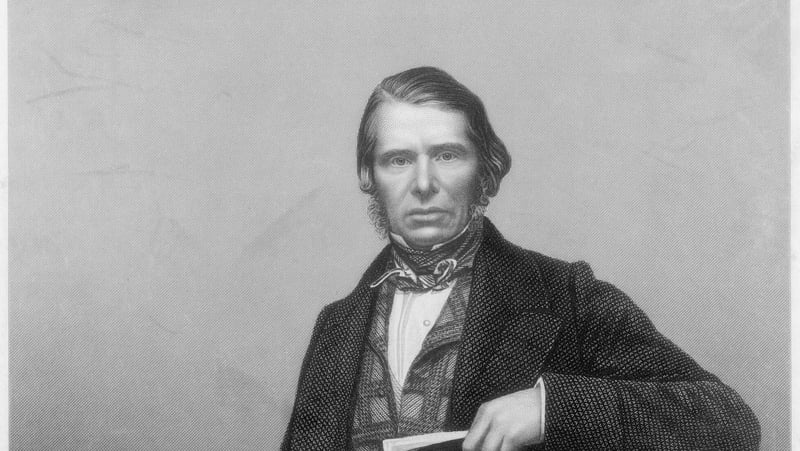

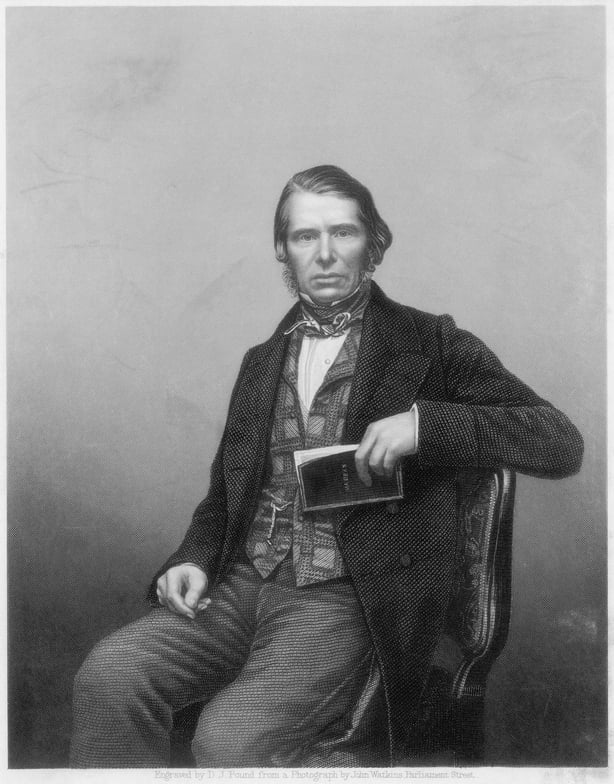

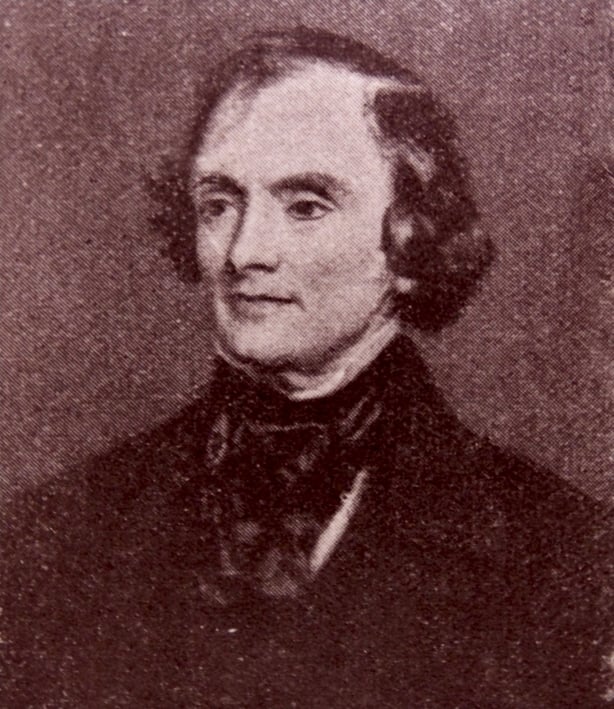

His name has become synonymous with British policy on Ireland during the Famine. What role did Charles Edward Trevelyan really play? Enda Delaney explains.

Charles Edward Trevelyan's name is etched in our understanding of the Great Irish Famine due to the reference to stealing 'Trevelyan’s corn’ in Pete St. John’s ballad, The Fields of Athenry (1979). Sung by Irish and Celtic football fans, it is the unofficial national anthem of both the Irish at home and across the Irish diaspora worldwide.

St. John’s inclusion of Trevelyan’s ‘corn’— that is food exported from Ireland during the crisis — made sure his name would never be forgotten.

Trevelyan was not a politician: he was a career civil servant. As Assistant Secretary to the Treasury, he was the most senior official responsible for overseeing the British exchequer, taking up this post in 1840. Born the fourth son to an Anglican clergyman in 1807, at Taunton, Somerset, the Trevelyans were a branch of a distinguished Cornish gentry family.

Charles was educated locally before attending Charterhouse School (then in central London), then Haileybury, the East India Company training college. One of his teachers at Haileybury was the Rev. Thomas Malthus, the well-known author of An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), in which he argued that a famine would act as a preventive check on population growth, an influential view in the first half of the nineteenth century.

At eighteen he was sent to India to study at Fort William College, Calcutta, where he excelled in Indian languages, and was appointed to a post in Delhi in 1827.

Fearless and Opinionated

Trevelyan had a very successful career in India, including famously denouncing one of his superiors for bribery, a case which was upheld and led to the subsequent dismissal of Sir Edward Colebrooke in 1829. This event established his credentials as a fearless and opinionated public servant who was not afraid to challenge his masters.

He was later appointed to the Political Department of the government of India, working closely with the reformist Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General of India (1828-1835), who later said of him:

‘That man is almost always on the right side in every question; and it is well that he is so, for he gives a most confounded deal of trouble when he happens to take the wrong one’.

He met his wife, Hannah More Macaulay, daughter of the abolitionist campaigner Zachary Macaulay, through her brother, writer and politician, Thomas Babington Macaulay. Trevelyan and Hannah were married in India in 1834. On furlough back in England from June 1838, he was unexpectedly appointed to the post as Assistant Secretary to the Treasury in January 1840, just as he was about to return to India.

A brutal attitude

Trevelyan’s major reform was introducing the principle of open competition for British civil service appointments as part of his role in the drafting of the Northcote–Trevelyan report (1854) for which he is widely credited, reforming a process that was previously characterised by patronage and corruption. His record on the Great Irish Famine is much more controversial, however.

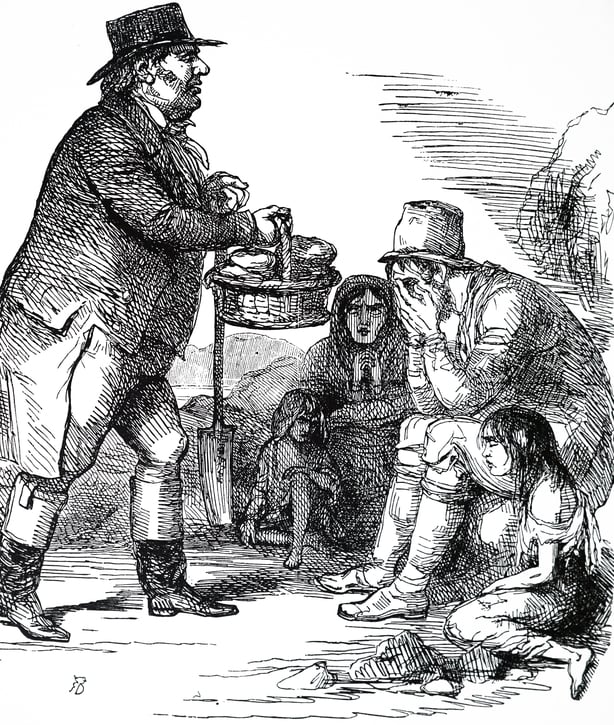

First and foremost, Trevelyan saw his role as essentially limiting the financial exposure of the British exchequer to funding relief for the Irish poor whose lives were devastated by the failure of the potato crop over successive years after 1846.

This point emerges again and again in the official papers produced by Trevelyan and used by historians such as Cecil Woodham-Smith and others to characterise his rigidity, punctiliousness and, at times, brutal attitude to upholding the financial rules he devised and then insisted were followed by subordinate officials in Ireland.

That’s not to suggest his contribution was not important; in fact, he demonstrated impressive leadership in directing and supervising the official relief effort between September 1845 and September 1847 when the ‘exceptional’ measures were wound down.

He rightly took credit for the operation of the soup kitchens which at the peak of August 1847 were feeding upwards to three million people, a major achievement. His work ethic was also equally impressive during these years, working from early morning until late at night dealing with what he called the "Irish crisis’ on top of his normal duties as head of the Treasury.

Self-satisfied

His own self-satisfied account of the programme of relief, first published anonymously in early 1848, then under his own name the same year, shows that he understood the issues of a 'famine of the thirteenth century acting upon a population of the nineteenth century', as Lord John Russell put it, even if his understanding of his society was shown to be wholly inadequate.

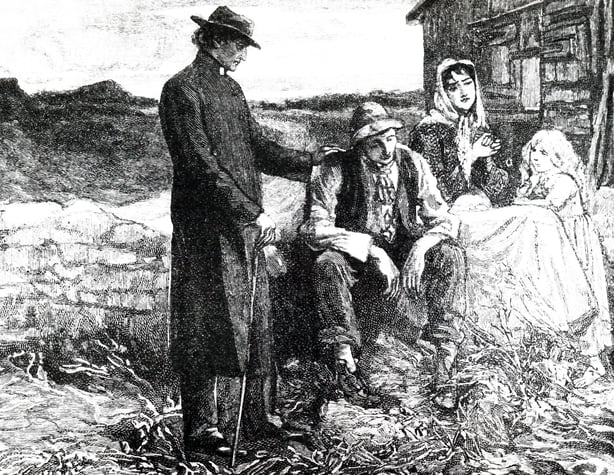

Trevelyan relied heavily on officials on the ground such as Sir Randolph Routh, head of the Famine Relief Commission, who played a prominent role in organising the distribution of relief, especially supplies of grain.

Equally well-informed correspondents such as Fr Theobald Mathew, the temperance campaigner, kept Trevelyan informed about events as they unfolded in Ireland.

Racist stereotypes

Any suggestion of fraud or the misuse of public funds was a constant preoccupation of Trevelyan. In part this was an understandable concern in the context of emergency relief, but it was also shaped by racist stereotypes about the Catholic Irish, often articulated in the British newspaper press.

There's no evidence that Trevelyan himself held such views: it was more a case that he feared that any corruption or fraud would be exposed, and he would be held accountable for financial mismanagement. This is why he insisted the documentation was made available to parliament and the wider public.

Undermining his political masters, regardless of whether they were Tories or Liberals, when he believed them to have arrived at the incorrect judgment was another tactic he used to contest decisions he disagreed with. Anonymous, and even signed, letters to the newspapers were his favoured tactic in this regard.

Any assessment of Trevelyan’s role must concentrate on the record of the government in preventing loss of life. On this measure the relief efforts that Trevelyan designed and implemented fell far short of what was needed, since at least one million people perished.

Concerns about eligibility, putting people to work for relief, and generally placing obstacles in the way of those most in need of help, were misplaced and wrong-headed.

Trevelyan was, of course, not a politician, so in that respect all policy decisions were taken by the Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer, but he did insert himself into all the key decisions as someone who claimed unique authority through his considerable expertise.

Social engineering with horrific consequences

What he shared with the politicians and indeed the British Establishment as a whole was an ideological outlook that saw the Great Famine as an opportunity to bring about far-reaching reform of Irish society, clearing the land of the poor, developing commercialised agriculture, and making the Irish economy more ostensibly modern.

This fused with his providentialist evangelical outlook, assured Trevelyan that his actions were appropriate and justifiable. He reflected that ‘we are advancing by sure steps towards the desired end’ and saw the great loss of life as a regrettable but unavoidable consequence of this programme of reform and regeneration.

Using the opportunity of the Famine to enact a programme of social engineering was both morally reprehensible and inhumane, and had horrific consequences for the poorest and most vulnerable.

No remorse

Ironically Trevelyan and his political masters, especially the Prime Minister from 1846 Lord John Russell, never acknowledged any regret or remorse about the terrible events which unfolded in Ireland between 1845 and 1852.

Trevelyan was knighted in 1848 for his work on Irish famine relief, and went on to become governor of Madras and finance minister in India in the 1850s and 1860s, before retiring to a life of charitable work, and becoming a landlord after inheriting the estate of Wallington, near Morpeth, Northumberland, from a cousin, and was created a baronet in 1874.

This piece is part of the Great Irish Famine project from RTE History and UCC and its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.