On De Valera's American trip, an Irish loan to the Russian revolutionary government led to the Russian crown jewels being given as security to the Irish delegation. So how did they end up in a suburban Dublin fireplace?

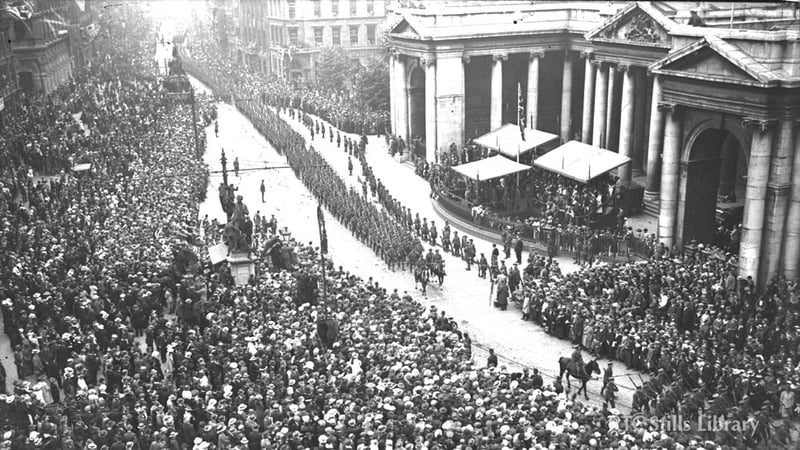

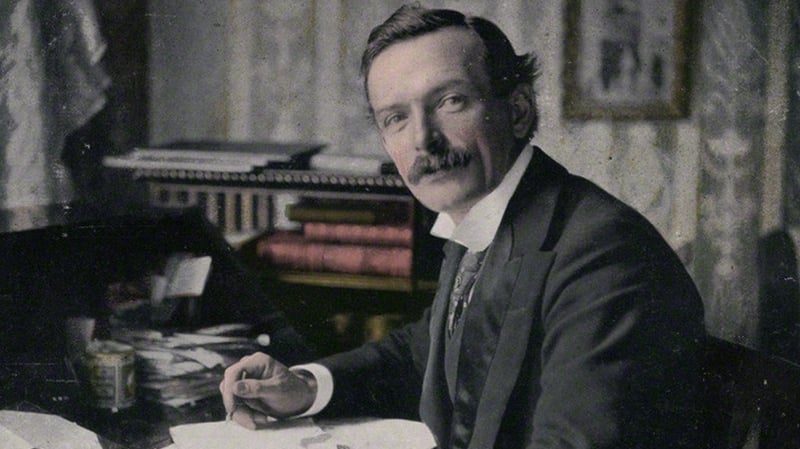

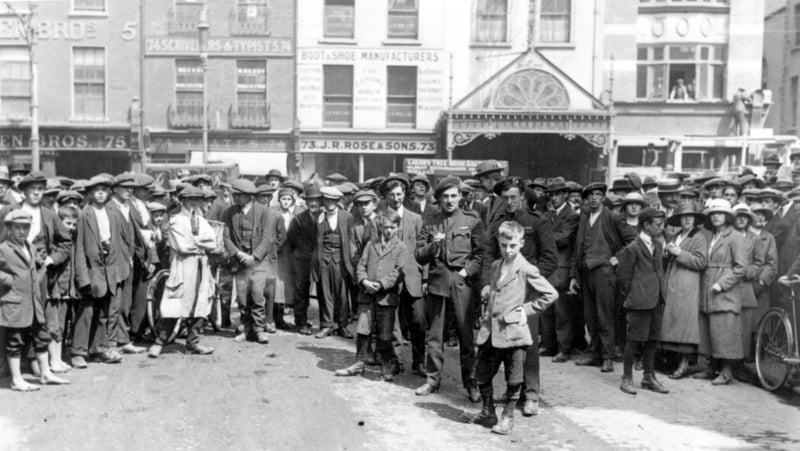

During his eighteen-month mission to the United States, Eamon de Valera packed stadiums and convention halls to rally Irish America to the cause of independence. Elaborate state receptions, flamboyant parades, enormous crowds and controversial rhetoric kept Ireland on the front pages of American newspapers.

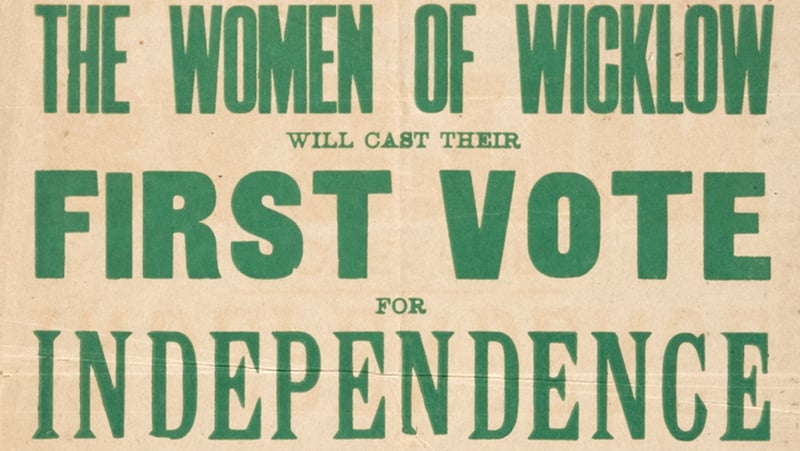

While the mission to gain official recognition for the Irish Republic failed, over 300,000 people subscribed to the Bond Certificate floated in January 1920, raising the modern equivalent of $55 million for the Irish cause.

In April 1920, part of this money was made available to representatives of the the revolutionary government of Russia who like the republicans, were in New York campaigning for American recognition of their cause.

And Ludwig Karlovich Martens offered, as security, the Russian crown jewels, seized by the Bolsheviks from the recently-executed Romanov family.

Harry Boland's sister Kathleen O’Donovan described the jewels in an interview with the Irish Press in 1948:

'There [were] four articles in all, including a big cluster, which might have been part of a crown – the earrings and the pendant. Diamonds with topaz, they are all mounted on platinum with safety locks.’

While O’Donovan presumed that the Irish envoys had ‘a sort of fellow feeling with the poor downtrodden Russian’, the action was justified by the republicans on the grounds that they hoped to secure recognition of the Republic from Russia.

Valuable cargo

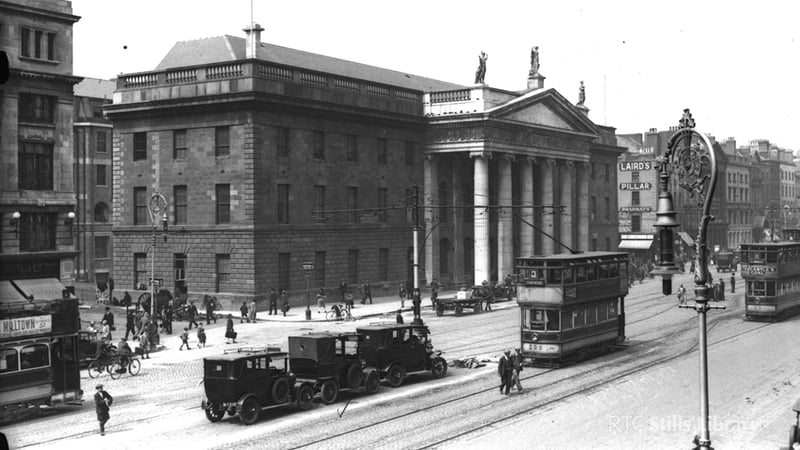

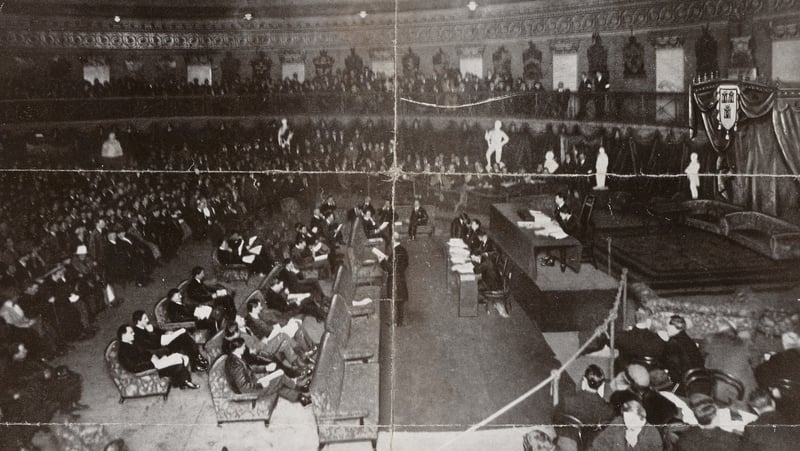

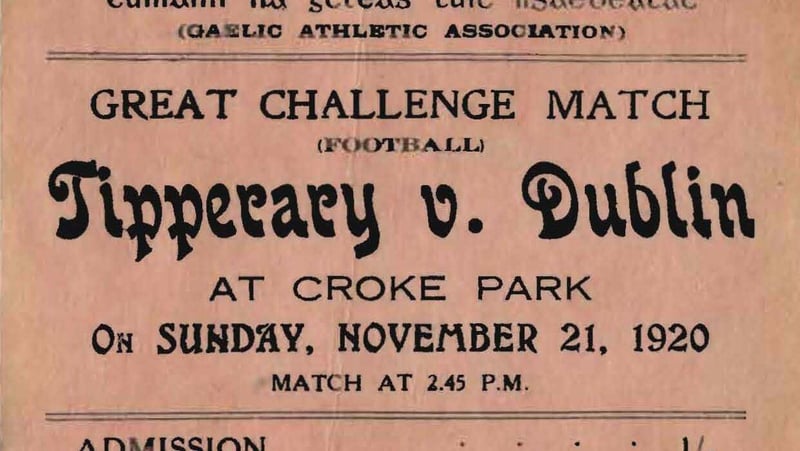

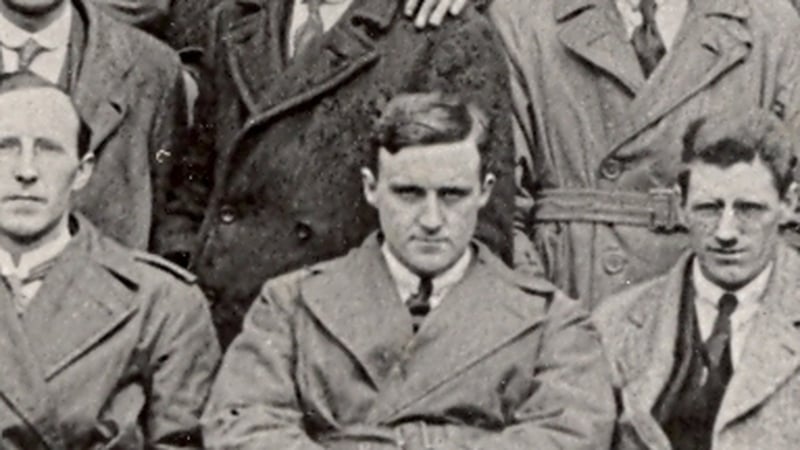

It would not have been prudent for the President of Dáil Eireann to carry the jewels on his return journey to Ireland, so Boland and Sean Nunan were entrusted with the valuable cargo. Nunan told the Bureau of Military History that about a week arriving in Cobh on 27 December 1921, ‘we reported to the Dáil, which was in session at Earlsfort Terrace, debating the Treaty. I accompanied Harry Boland to [Minister for Finance] Michael Collins, to whom the jewels were handed’.

In an interview in 2013, Kathleen Boland’s daughter, Eileen Barrington described how the Romanov jewels ended up in her grandmother’s house at 15 Marino Crescent:

The story I was told by my mother was that during an argument about the Treaty, Collins threw the jewels back at [Harry] and said, "Take them! I don’t want to touch them, there is blood on them." Harry stormed out and took them with him and gave them to his mother to mind.

She put them in the ash pit in the old range in the kitchen. My father, Seán O’Donovan, who was visiting the house, took a brick out of the back of the fireplace and put them into there, and there they stayed for many a long year. Then, when my father married my mother and he moved to 315 Clontarf Road, he took them with him.

My mother had, as a souvenir of her brother, Harry Boland’s riding boots and, as a child, I remember seeing them at the bottom of my mother’s wardrobe.

[Inside] they had a thing… to keep the boots in shape, but down at the bottom there was a space, and she hid the jewels down there.

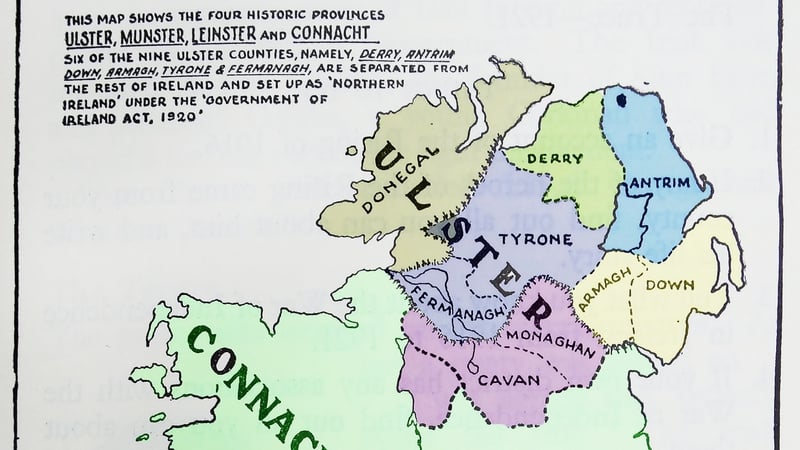

In December 1948, independent TD for Laois Offaly Oliver J. Flanagan sought clarification in the Dáil about the whereabouts of the Russian jewels between 1922 and 1948.

The issue had first been raised publicly during the 1948 election campaign by Dr Patrick McCartan, Clann na Poblachta candidate for Cork city, who, as Sinn Féin envoy in American in 1920, was aware of the loan.

A Soviet debt

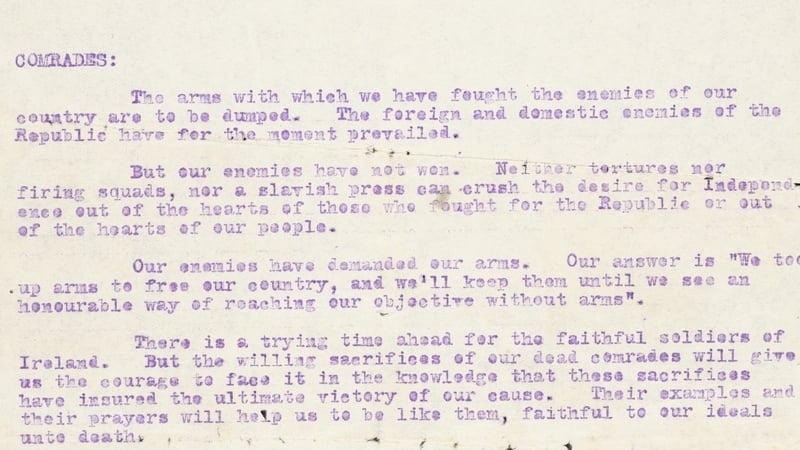

McCartan asked if Fianna Fáil would clarify whether the ‘money had ever been repaid by Soviet Russia and if not, where are the jewels of which their colleagues had custody?’ The revelation caused a media sensation and in a speech in Youghal in the same month, de Valera was forced to admit that the loan had never been repaid.

Sean O’Donovan wrote to the Irish Press in response to Flanagan’s query, explaining that the jewels had been in his possession until 1938, when he handed them back to de Valera.

On 18 November 1938, in the presence of two witnesses, Minister for Finance Seán MacEntee and Maurice Moynihan, Secretary of the Department of the Taoiseach, de Valera officially accepted the jewels into the custody of the state.

Revelations of a secret agreement with the Soviet Union would have been politically inexpedient in the late 1930s, so the jewels were kept safely hidden until McCartan’s public interrogation in 1948.

The loan is repaid

When Patrick McGilligan assumed the role of Minister for Finance in the first inter-party government in 1948, he decided to pursue the loan. The jewels were sent to Christie's auction house in London and valued at just £1,600, much less than the value of the loan in 1920.

When the government informed the Soviet ambassador of its intention to auction the jewels, the original loan of $20,000 was repaid, and the collateral returned to the Soviets. The transaction was completed on 13 September 1949.

As Seamus Murphy points out, the absence of any documentary evidence recording when the loan would be repaid and what interest rate would be applied, coupled with the subsequent deaths of the handful of people who knew about the loan, meant that if Patrick McCartan had not raised the question in 1948, the debt may have remained unaccounted for and the story of the Russian jewels lost forever.