Waterford sisters Hannah and Anna Meany were both nurses - and when WWI broke out, they became two of the more than 10,000 women who served in the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve, Britain's military nursing institution. While Hannah went to France, Anna went further afield - to what is now Iraq, where deadly diseases became the real enemy. In the latest installment in our Family Histories series, her great-nephew Paul Looby tells her story

My great-aunt, Anna Patricia Meany, was born in 1890 in Clonea near Dungarvan, County Waterford. She was the second surviving daughter of Dr Denis and Mrs Maria Meany. Anna was educated at the Convent of Jesus and Mary School in Willesden, London, before returning to the County and City Infirmary in Waterford to train as a nurse with her elder sister, Hannah.

Anna was 25 when the Great War broke out in August 1914. By the end of the year, the British Army had suffered 90,000 casualties on the Western Front. As military hospitals struggled with the vast numbers of wounded, the call went out for volunteer nurses. At that time, the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service was Britain's main military nursing institution. While it only admitted unmarried ladies of high social status aged 25 years or older, married women and those of humbler birth could join the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR). Over 2,200 women signed contracts with the QAIMNSR by the end of 1914, and over 12,000 enlisted over the course of the war. Among these was Anna, who applied to join the Reserve on April 15th, 1915.

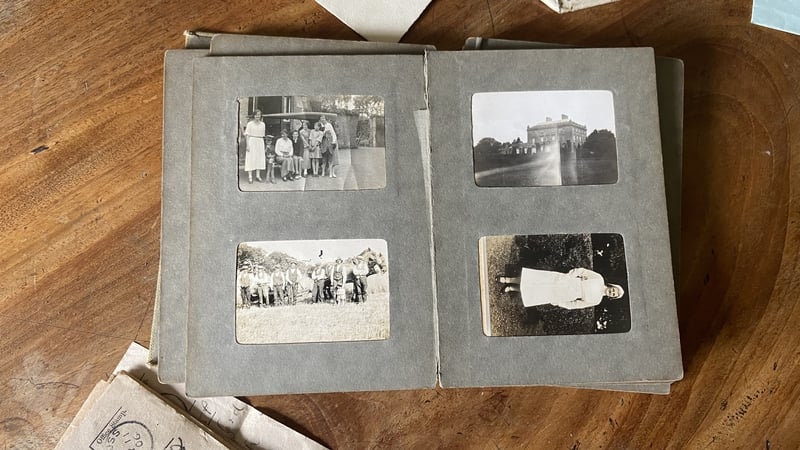

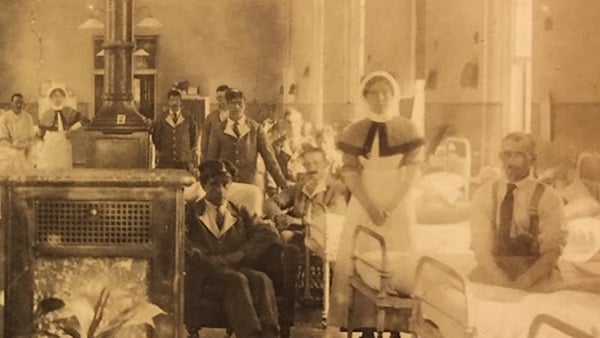

New recruits served probation in a hospital in Britain or Ireland before being considered for overseas service. Anna was assigned to Rubery Hill Asylum in Birmingham on June 1st, 1915. She arrived to find it being hastily converted into the 1st Birmingham War Hospital, which opened its doors on July 30th, 1915. Anna spent almost a year there tending to the casualties flooding in from the battlefields of France and Belgium. In one of the few photographs we have of her, Anna poses with several nurses, orderlies, and patients outside the chapel of Rubery Hill. The patients' injuries are all too obvious - arms in slings and empty sleeves. Remarkably, most manage a smile for the camera.

Off to Mesopotamia

Successfully completing her probation, Anna departed for a new posting on June 11th, 1916. However, she was not bound for France. Instead her itinerary took in Gibraltar, Suez, Aden, Bombay, and finally, on October 5th, 1916, the port of Basra, in what was then known as Mesopotamia, and what is now known as Iraq.

Over the next three years, Anna served in military hospitals in Basra (Number 3 British General Hospital: October-December 1916, February-May 1919), Amara (Number 2 British General Hospital: December 1916-April 1917), and Baghdad (Number 31 British Stationary Hospital: May 1917-January 1919), as war raged in the land between the rivers.

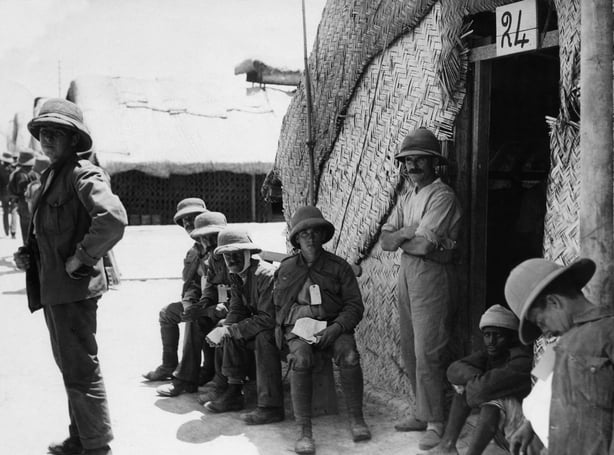

Extreme climate

Soldiers and nurses alike suffered the extremes of the Mesopotamian climate. Summers were scorchingly hot, with temperatures reaching the 40s and even 50s centigrade. In Basra, the heat was exacerbated by high humidity. Heatstroke and sunstroke sickened and killed thousands. Anna and her fellow nurses worked without air conditioning, setting up special heat wards with electric fans and ice to keep patients cool.

Fevers proved especially deadly in the heat, and fever-patients were covered with damp sheets and placed under fans in the coolest part of the ward. Winters offered little respite. Between November and April, torrential rains turned unpaved streets into quagmires of mud, while the Tigris and Euphrates overflowed their banks, flooding vast areas.

The Shamal wind brought dust and frigid air down from the snow-capped mountains of Anatolia. Tents and accommodation built for hot weather offered no insulation against the winter cold. The nurses vainly attempted to heat the draughty wards with portable stoves to keep the patients warm.

Deadly disease

Unsurprisingly, disease inflicted more casualties in Mesopotamia than enemy action. Swarms of mosquitos and sandflies spread malaria and sand-fly fever in their wake. Other common insect-borne diseases included typhus, relapsing fever, and bubonic plague. Contaminated food and water caused paratyphoid, typhoid, amoebic and bacterial dysentery, and cholera.

Between 1914 and 1918, 11,008 British and Indian troops were killed in action in Mesopotamia, while another 51,386 were wounded. In the same period, a staggering 820,410 were hospitalised for "non-battle" reasons - an average of two hospitalisations per man deployed. Medical staff were no less susceptible, and Anna suffered three bouts of "debility", the first in April 1917 in Amara, the second in July 1918 in Baghdad, and the third in April 1919 in Basra.

No armistice with disease

On October 30th, 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros, ending their involvement in the war. The Mesopotamian campaign was over, and two weeks later so too was the Great War. However there was no armistice with disease and the work of Anna and her nursing sisters went on. She remained in Baghdad until mid-February 1919 before being recalled to Basra.

The matron of 23rd British Stationary Hospital, Ms M Walker, wrote of Anna on her departure from Baghdad:

"I consider her a thoroughly well-trained nurse. She takes a great interest in, and is most kind and attentive to her patients. Her powers of administration and initiative are excellent. She is reliable, punctual, tactful, and good-tempered. I recommend her for further service if required and for full gratuity."

In her three years in Mesopotamia, Anna had only three months of leave between January and March 1918, which she spent in India. Nonetheless, she was rewarded for her dedication with a promotion to the rank of Sister on August 1st, 1918. On June 3rd, 1919, Anna received the Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class in recognition of special devotion and competence while nursing the sick and wounded of the British army. The medal’s first recipient was Florence Nightingale in 1883. The 2nd Class award, instituted in November 1915, was awarded to 6,419 women during the Great War.

Leaving Basra

On May 4th, 1919, Anna departed Basra aboard the hospital ship Aronda bound for Bombay. She arrived in Southampton on November 12th, 1919, and was officially demobilised on December 15th. She had served in with the QAIMNSR for a total of 4 years and 64 days.

However, her nursing days were not behind her. Anna enrolled into the Permanent Reserve of the QAIMNSR on April 22, 1921. On June 30th, 1922, she joined the staff of the Ministry of Pensions veterans’ hospital at Leopardstown Park in Dublin. This was based in the country manor of Ms Gertrude Dunning, who granted the house and grounds to the British government in 1917 on condition it be used for the treatment of war veterans. It was initially used as a convalescent home for those suffering from shellshock.

After 1931 Leopardstown Park extended its services to include general medical care for veterans, particularly the maintenance of artificial limbs. It continued its work through the decades, admitting non-veterans from the 1970s onwards, before finally being transferred to the Department of Health in 1979.

Anna remained at Leopardstown Park for the rest of her working life, caring for those who bore the visible and invisible wounds of war. In 1941 she married Richard P. Quinn, an Irish veteran of the Great War. Their married life was short - Richard died only eight years later, aged 56. Anna did not remarry. She lived on St Helen’s Road, Booterstown until her death in November 1979. She is buried beside Richard in an unmarked plot in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Read about Anna's sister Hannah and her very different wartime experiences here.

Do you have a story to tell about your own family's experience of significant historical events? Find out how to contribute it here. Have you ever seen a member of your family in a historic photograph? Explore our Civil War Ireland then and now series here, and explore our history galleries here.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ