The first executions took place on 17 November 1922. Four young Dubliners were shot at Kilmainham. On the night before his execution, eighteen-year-old James Fisher wrote home: 'Oh mother, if I could only see you again...'

But there were no last visits and just after dawn on 17 November, the four young men faced a firing squad. Three died instantly, the fourth, twenty-one-year-old Peter Cassidy was mortally wounded. The young officer commanding the firing squad lost his head and made to call an ambulance. But then, recovering his composure, he turned, pulled out his revolver and shot Cassidy dead. The failure of firing squads to perform well would be a painful, recurring theme in the months that followed.

The families of the executed men would learn of the death of a loved one through a pro forma shoved through the letterbox or in the afternoon paper. By the end of the war eighty-one men had been executed and hundreds more were under sentence of death.

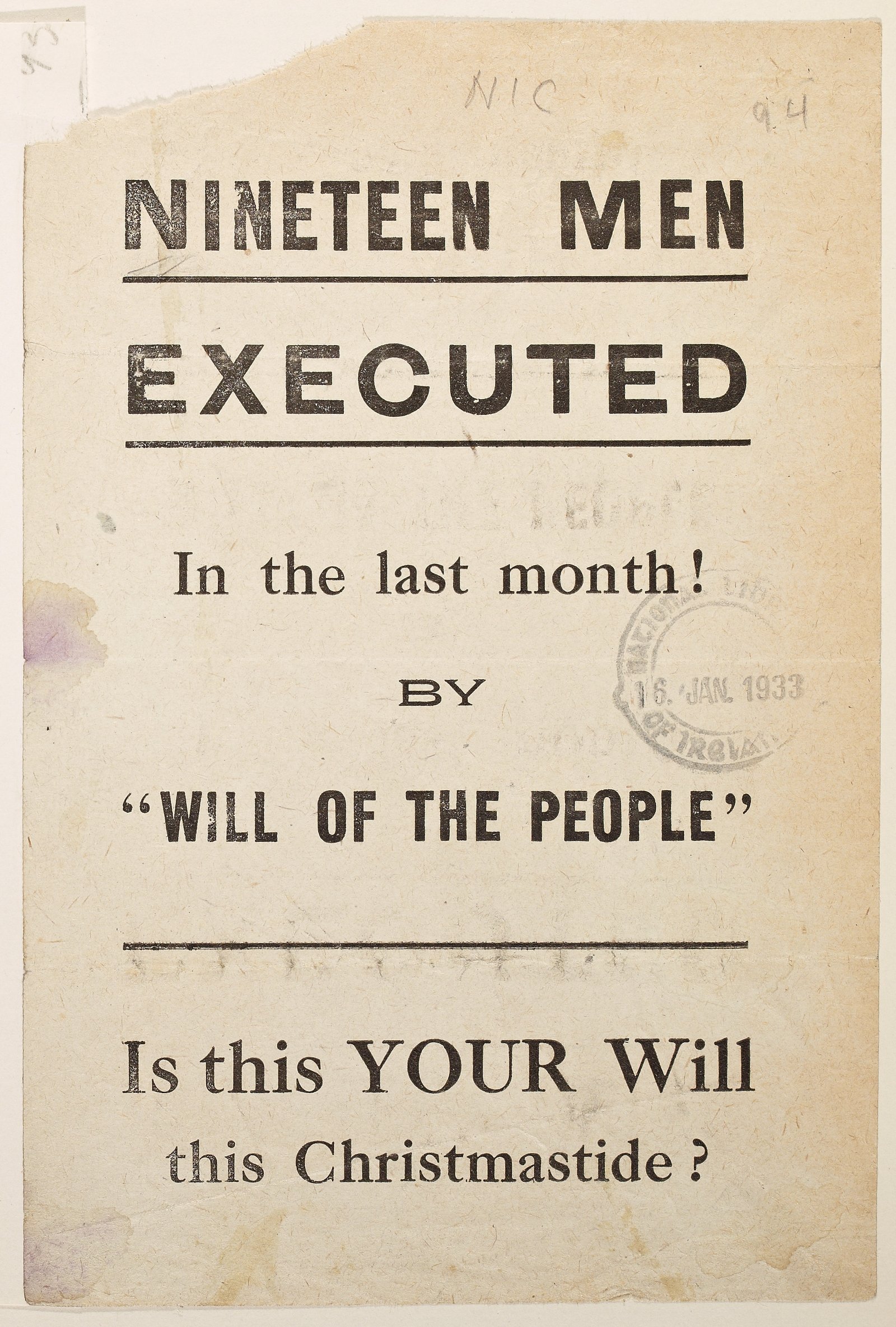

Anti-Treaty leaflet referring to executions 'by will of the people', asking the reader, 'Is this your will this Christmastide?' Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

How it came about

This prospect of the money running out was the driving fear: the public sector pay bill could no longer be met; the police, army and civil service would unravel, and the British Government might once again send in the troops. It was in this context that the Provisional Government formulated the execution policy.

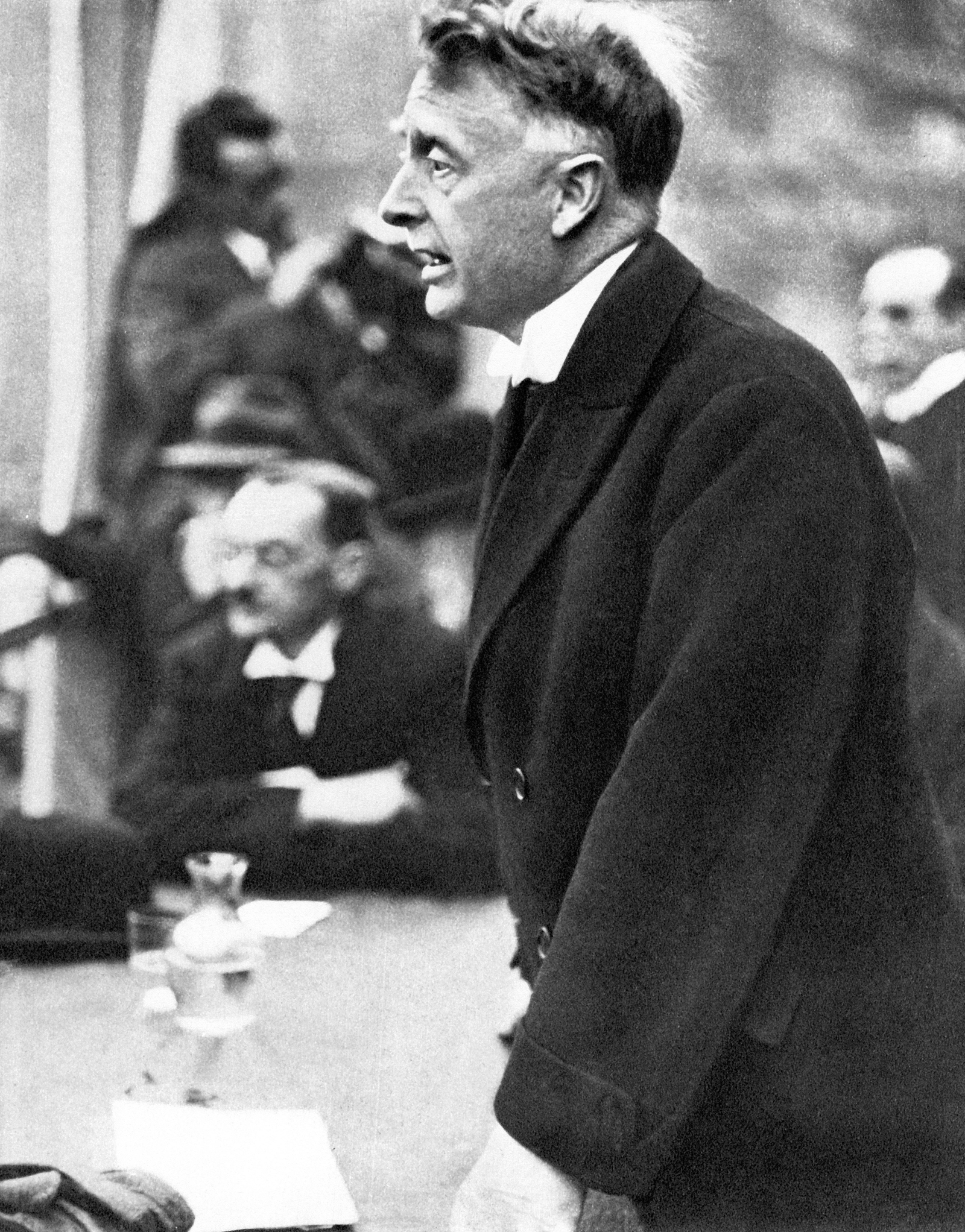

W.T. Cosgrave became President of Dáil Éirean in September 1922, not long before the Dáil approved new regulations for the trial of suspects working against the government. Photo: Culture Club/Getty Images

The motion was easy enough to pass the Dáil, which possessed a strong pro-Treaty majority and lacked most of its anti-Treaty TDs, who were in the country fighting against the government. Political constraint was further limited by the strict press censorship regime which operated at the time.

During the Dáil debates, TDs were assured by the government that the trials would be fair and that prisoners would have defence lawyers. As a result, the Army (Special Powers) Resolution was passed, and the Dáil approved regulations for the trial of suspects.

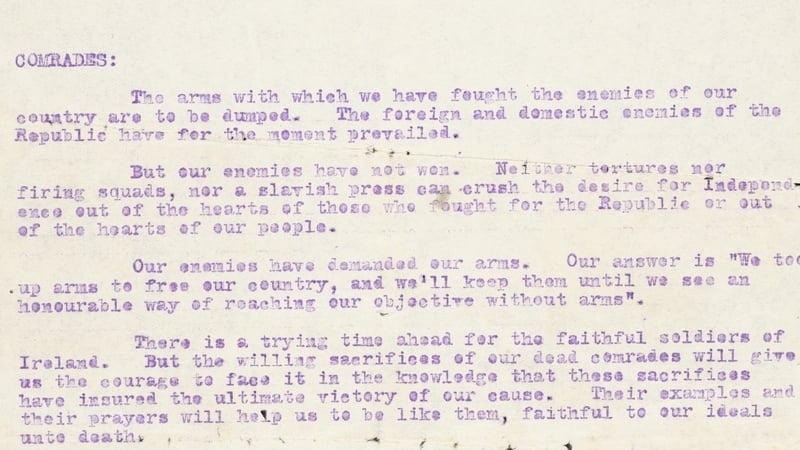

At the request of the government, the National Army issued a proclamation that persons 'taken in arms' or 'attacking national army troops' would be tried by military court and 'suffer death.' The executions began.

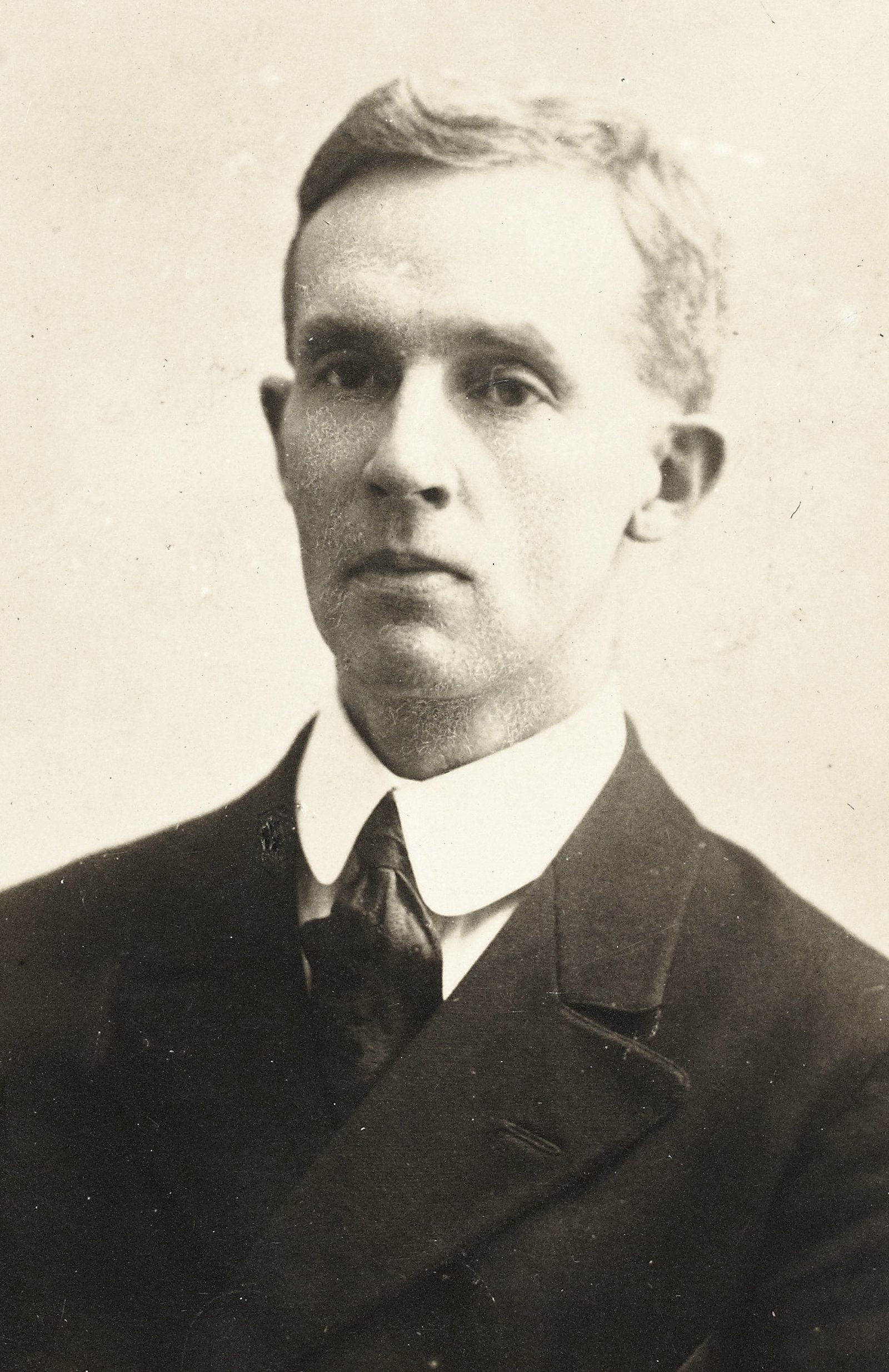

Erskine Childers, whose capture led to an early crisis in the execution policy. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The first crisis

Just a week after the first executions, the government faced a crisis in its execution policy. Erskine Childers was captured in possession of a handgun, tried, convicted and sentenced to death. He promptly brought a legal challenge to the execution policy in the High Court by a writ of habeas corpus. However, the High Court declined to intervene, and the next round of executions began.

On 8 December 1922, the government went a step further and executed four prisoners without trial as a reprisal for the shooting of Séan Hales TD the previous day.

The funeral of Seán Hales, whose shooting triggered the execution of four men without trial. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The end of the rule of law

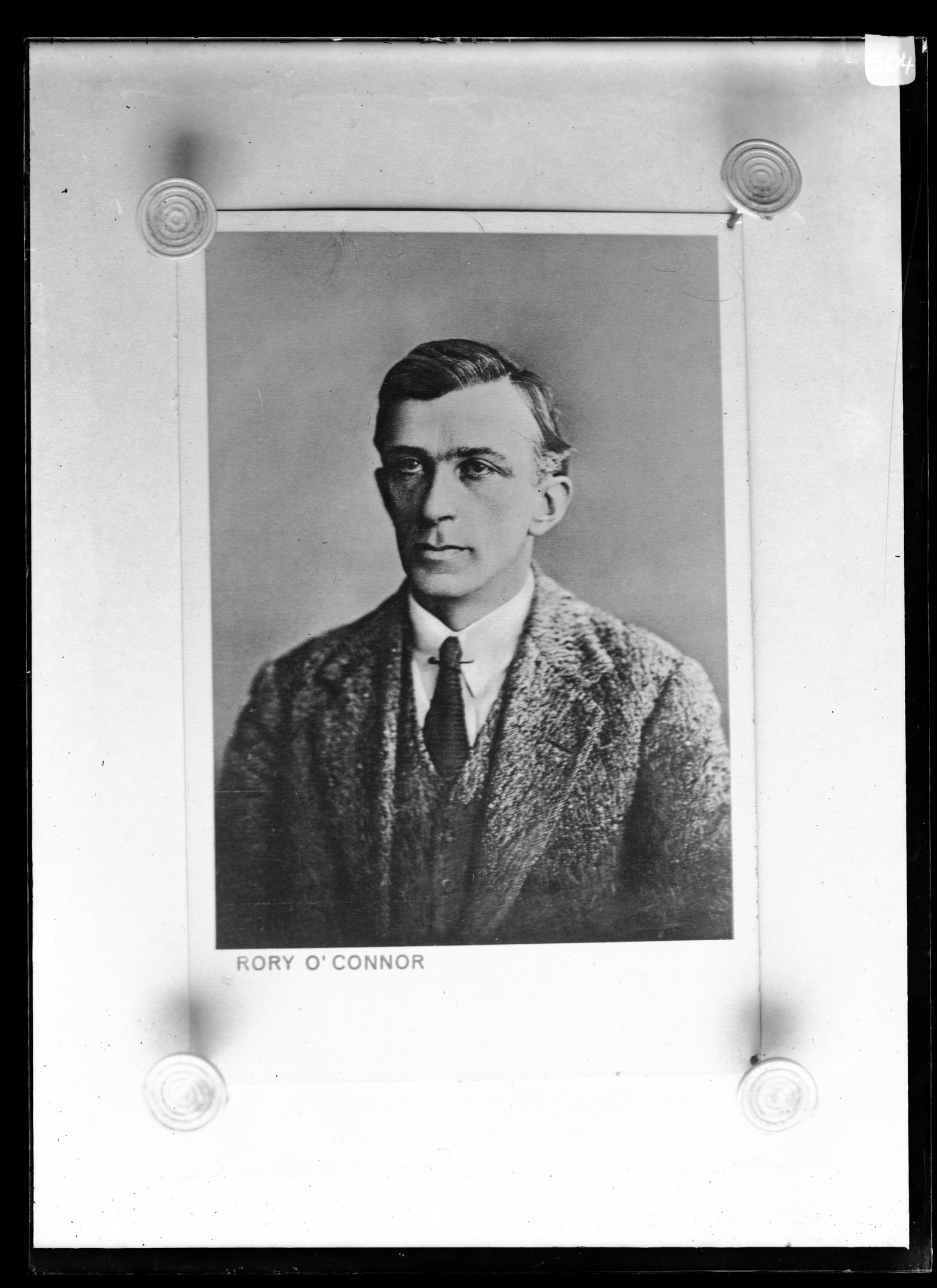

The four men who had been captured during the Four Courts battle in June included two of the most prominent anti-Treaty IRA leaders, Rory O'Connor and Liam Mellows. The Mountjoy executions, as they became known, marked the abandonment of the rule of law.

The same morning General Mulcahy ordered the creation of Army Committees which would substantially replace military courts.

Rory O'Connor was one of the most high profile republicans to be executed. Image © RTÉ Photographic Archive

Trial by Army Committee

It was intended that Army Committees would deal with cases where there was no factual dispute, but the proclamation did not say that: it simply related that trial by Army Committee had been introduced. There was a subsidiary difficulty in that the decision as to whether a particular case involved a factual dispute was made by army lawyers and simply pre-judged the entire trial.

The trial regulations approved by the Dáil were swept away by Mulcahy. This new Army Committee system was soon refined again and became the new normal for all but a handful of prisoners. Trial would follow immediately after capture; there would be no delay and no defence lawyers.

The last letters home of a few prisoners provide a glimpse of what took place. Patrick Hennessey from Clare was convicted of possessing a few rounds of ammunition and causing damage to the rail network. His last letter to his family reads:

'We were tried at midnight ... called from our cells where we were asleep, got no chance to defend ourselves ...'

Friend against friend

Kevin O'Higgins (centre) married Bridget Cole on 27 October 1921 in the Carmelite Church in Whitefriar Street, Dublin. In attendance were Éamon de Valera as well as O'Higgins's best man, Rory O'Connor (right). O'Higgins and O'Connor were both educated in Clongowes Wood College and University College Dublin and their friendship was forged during the War of independence.

In 1922 O'Connor, who was wounded in the Rising, opposed the Treaty, sticking steadfastly to the Republic declared in 1916. O'Higgins, however, supported Collins's assertion that the Treaty represented an opportunity to attain full freedom. Close bonds of friendship that formed during the struggle for independence were sundered in the subsequent Civil War – none more tragic than O'Connor and O'Higgins's.

Rory O'Connor was imprisoned in Mountjoy Jail after the surrender at the Four Courts and was executed on 8 December 1922 in reprisal for the killing of Seán Hales TD outside Leinster House the previous day. Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O'Higgins was involved in the decision to execute O'Connor along with three others, Richard Barrett, Liam Mellows and Joe McKelvey. Photograph courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Conviction by Committee

Mulcahy's committee system became the usual method of trial. These Army Committees could decide verdicts on the case papers, sometimes without hearing from the prisoner or his witnesses. Conviction put the fate of the prisoner in the hands of the confirming body: General Mulcahy and the Army Council. Here, intelligence about the prisoner and strategic considerations would determine who would die and who would be spared; for these men there was no appeal.

Martyrs or innocent victims?

After execution, the prisoners were promoted as heroes by anti- Treaty propagandists, which has obscured the unpalatable fact that it is likely that a small number of prisoners were not guilty of the charges they faced. Most of the prisoners' last letters speak of resignation, dying for the cause, the love of families and regret about a life cut short. The letters of two prisoners, however, are markedly different. 'Our lives are sworn away', wrote Patrick Hennessey, ... 'We are innocent'.

In Clare, another prisoner, Patrick Mahoney saw the priest for the last time and sat down to write to his family: 'I am innocent...' The context was ripe for miscarriages and these letters, written after seeing a priest and receiving absolution, might give cause for disquiet.

Richard Mulcahy, seen here during the lying in state of Michael Collins. Photo: Central Press/Getty Images

Reprisals

The focus of the execution policy was on the anti-Treaty rank-and-file rather than the leadership. Half a dozen anti-Treaty TDs were captured with arms, but neither they, nor the many high-ranking anti-Treaty IRA officers who were captured, were executed.

In January the execution policy was ramped up: thirty-five executions took place. The focus remained on the rank-and-file but shifted to local executions and then to reprisal executions. General Mulcahy ordered that 'in every case of outrage in any battalion area, three men will be executed.'

By this time, there was a large number of prisoners under sentence of death in makeshift prisons across the country. Here, perhaps, is the ugliest truth. When troops were attacked, the Army searched through the list of prisoners under sentence of death and executed prisoners from the area where the ambush had taken place. Whether by chance or design, the policy of the National Army had morphed into reprisal executions.

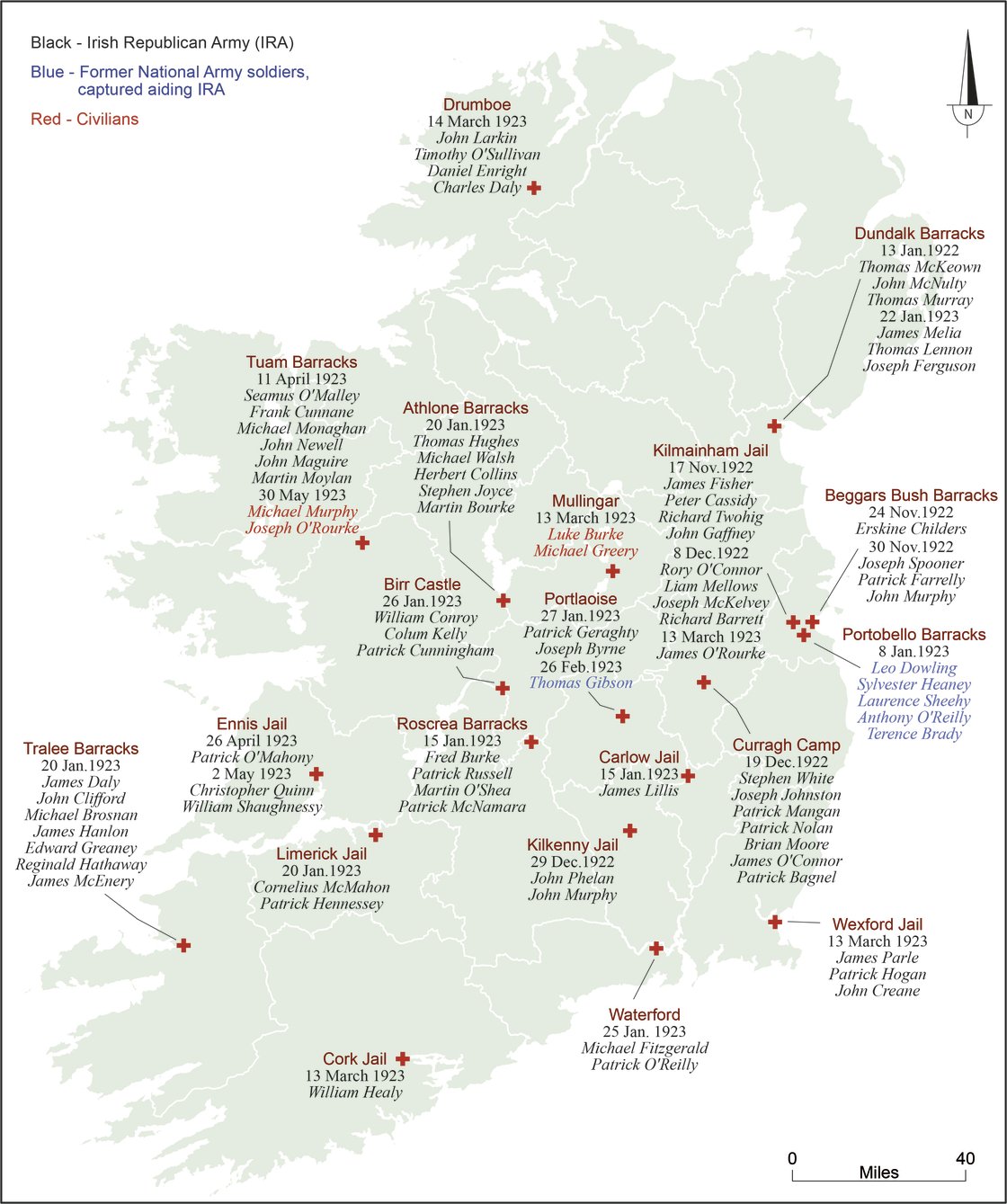

The 'official' executions carried out by the Provisional Government/Free State, 17 November 1922 -30 May 1923.

The policy of executions marked a more ruthless phase of pro-Treaty policy in the Civil War. The majority of the executions were carried out under the emergency powers adopted by the Third Dáil in late September 1922, which allowed for military courts. Death sentences could be issued for the possession of arms or aiding and abetting attacks on the National Army. All those killed, with the exceptions of Erskine Childers, Charlie Daly, Liam Mellows, Rory O'Connor and Joe McKelvey (the latter three executed outside the terms of the law) were essentially IRA foot soldiers. All but eighteen of the executions occurred outside of Dublin, a deliberate policy adopted after the initial dozen men were killed in the capital.

Return of law

The justification for trials by military court rested on the contention that ordinary law had broken down and the Army needed to 'stand in the gap', as General Mulcahy told the Dáil. That may have been so in the autumn of 1922, but the anti-Treaty faction had collapsed by the spring, and executions continued until well into the summer.

The war was over by the late spring of 1923 and in the summer, with some difficulty, the Dáil began to wrestle control back from the National Army.

After the war, the government passed the Indemnity Act to protect those who had taken part in military courts and the suppression of the anti-Treaty cause. It did not render lawful what had been done, but it prevented anyone bringing a legal action. It is an ugly story, but this is how the state was founded.

This article is part of the Civil War project coordinated by UCC and based on The Atlas of the Irish Revolution edited by John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy and John Borgonovo. Its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.